|

Real Fuerte de la Concepción

Aldea del Obispo, Spain

|

|

|

Constructed: 1664, 1736-1758

Used by: Spain, France,

Great Britain, Portugal

Conflicts in which it participated:

Peninsular War

|

Spain and Portugal, two great nations that spread the art of European starfortery far and wide during the Age of Discovery and beyond, have a long and tortured relationship. The starfort of our current interest came into being thanks to the deterioration of the Iberian Union, in which Portugal semi-voluntarily became a pseudo-vassal state of Spain from 1580 to 1640.

When Spanish King Philip III (1578-1621) passed away and magically became Philip IV (1605-1665), things were about to get much worse for Portugal's nobles.

|

|

|

|

Philip IV (who was known as Philip III in Portugal, as he was the third such Philip to rule over Portugal since the onslaught of the Iberian Union) wanted to make Portugal a mere province of Spain, which would have spelled doom for any power Portuguese nobles still held. This being the final straw, the Portuguese Restoration War (1640-1668) did what its name suggested, and brought an end to the Iberian Union.

...at least it brought an end to the Iberian Union as far as everybody but Spain was concerned. Unsurprisingly, Spain liked the Iberian Union, and would have been quite pleased to continue as the senior partner in this now-defunct arrangement. Spain therefore had an interest in recovering its wayward unionmate, and needed a bunch of starforts along its lengthy border with Portugal to utilize as forward operating bases for the eventual reconquista.

|

Nearly as important as a Spanish starfort itself is the coat of arms that has been lovingly carved above its entrance. In this case it's the coat of arms of King Philip IV (I think?), who was the dude in charge of things when the Real Fuerte de la Concepción was built. |

|

Spain could petulantly say that Portugal started the massive arming of the border, at least in the region in question, when Portugal upgraded an old fort at the town of Almeida into a stellar fortified village in the 1640's. A young Father of the Starfort (Vauban (1633-1707)) may have worked on that fort in its latter stages of development. Faced with such a clear and present danger just a few miles from its border, how could Spain not up the ante with a starfort of its own? Gaspar Téllez-Girón (1625-1694), 5th Duke of Osuna and commander of the Spanish military, ordered the construction of a new starfort to check the wicked aggressiveness of Almeida (but mostly to use as a stepping stone for an invasion into Portugal). Work on this new fort began on December 8, 1663, which, conveniently, fell on the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, giving them a slam-dunk name for their new starfort! |

|

The Feast of the Immaculate Conception, held on December 8, of course celebrates the conception of Jesus Christ (0-33AD)...but assuming that immaculate conception leads to a standard human gestation period of nine months, we should really be celebrating Christmas on September 8, shouldn't we? But September 8 is the Nativity of Mary, a feast day that celebrates the birth of Mary, Miss Immaculate Conception Year -1 herself. Nobody was interested in questioning this seeming incongruity in 1664, and the new starfort was named Real Fuerte de la Concepción, Royal Fortress of the Conception.

The first version of our fuerte was completed in just 40 days, under the direction of French military engineer Simon Jouquet. It was a huge but relatively simple affair, with four earthwork bastions around a large central courtyard, and earthwork walls connecting the bastions. Further earthworks and redoubts made of earth (lots of earth was moved about for this fuerte!) and wicker woven around timber stakes, plus brush fascines surrounded the whole affair, which was immediately ready for a garrison of 1500 infantrymen and 200 cavalrymen.

|

Unfortunately for the fuerte de nuestro interés actual, the man who had initiated its construction, the Duke of Osuna, was shamed at the Battle of Castelo Rodrigo (July 7, 1664). This Castelo, which is about twelve miles north of Almeida in Portugal, was attacked by 7,000 Spaniards under the Duke. The 150 men defending the castelo managed to hold off the Spanish until 3,000 Portuguese troops arrived, routed the attackers and captured all of their artillery. Having lost the battle, the Duke of Osuna escaped capture by dressing as a monk and slinking away. Losing this seemingly unlosable battle caused Osuna to be stripped of command, but also somehow reflected poorly on the Real Fuerte de la Concepción...because King Philip IV, having taken over command of Spain's armed forces, immediately ordered its partial destruction. That'll show the Portuguese and/or the Duke!!

|

|

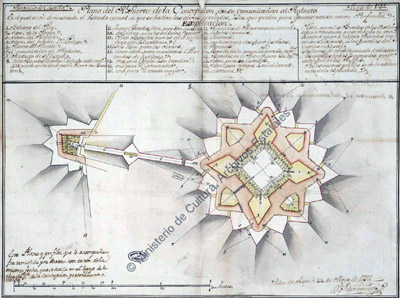

The Fuerte in 1737, after its first major facelift. Yes we get it, Ministerio de Cultura, Archivos Estatales. This image belongs to you and only you. The Fuerte in 1737, after its first major facelift. Yes we get it, Ministerio de Cultura, Archivos Estatales. This image belongs to you and only you. |

|

Spain finally gave up on its immediate hope of consuming Portugal and recognized it to be an independent kingdom in 1668. The border was still a 750-mile-long potential flashpoint, however, and when Spain's King Philip IV became the V in 1700, there was a renewed interest in strengthening that border.

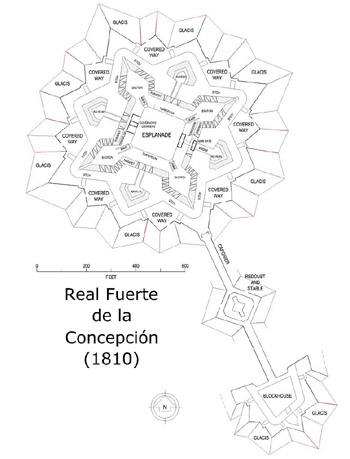

In May of 1736, work commenced on the resurrection of the Real Fuerte de la Concepción. Built more or less in the footprint of the original fort, its most curious feature, the extended thing sticking out to the fuerte's southwest that looks a bit like it's fishing for trout, was likely added during this period. The furthest extent of this outerwork is known as the Blockhouse, though it seems 'twould be more accurately described as a hornwork...but the Spanish built it, so they may call it whatever they like. This macelike protuberance is connected to the fuerte by a covered way, with another redoubt, which also served as the fuerte's stables, halfway along.

The second iteration of the fuerte was completed in 1758, just in time for it to be ready for the Anglo-Spanish War (1762-1763), which was an offshoot of the always-popular Seven Years' War (1756-1763). During this conflict the Spaniards indulged their fondest wish and invaded Portugal, three times, once with the assistance of their allies the French...but on each occasion they were beaten back by the Portuguese and British armies, aided by an extremely irate Portuguese populace. The Real Fuerte de la Concepción was indeed used as a cantonment, a military headquarters for the invasion, but there was no fighting in our fuerte's immediate vicinity.

|

The fuerte in 1810, at the height of its mystical powers. The fuerte in 1810, at the height of its mystical powers. |

|

At the dawn of the 19th century, Napoleon (1769-1821) came along and further screwed up an already-pretty-darned-screwed-up European continent...although to be fair, the French Revolution had been responsible for plunging Europe and much of the rest of the world into war, not Napoleon. Napoleon was just really good at the war thing!

Spain got to do the thing it wanted (again), which was invade Portugal (again) in 1807, once more with the assistance of the French. This invasion went particularly well at first, resulting in an almost bloodless takeover of Portugal...but one allied with Napoleon at one's own risk. 1808 saw France taking over Spain and installing Napoleon's brother, Joseph Bonaparte (1768-1844) as its king.

The Spanish garrison at the Real Fuerte de la Concepción were introduced to this new reality when a French column under General Louis Henri Loison (1771-1816) appeared at the fuerte's gates, announcing that they had arrived to relieve the garrison. The fuerte's small Spanish garrison, aware that something was amiss, wisely slipped out the back door, and the Real Fuerte de la Concepción had new owners; and they ate snails! Because they were French, y'see. |

|

Despite the French possession of both our fuerte and the Fortress of Almeida, Loison did not enjoy a smooth occupation experience on the Spanish/Portuguese border. As irate and effective as guerilla fighters the Portuguese people had proven to be in the previous conflict they had enjoyed, the Spanish people seemed even less appreciative of foreign domination. Loison spent all of his time marching his column about, attending to various uprisings and other forms of well-earned unpleasantness. When his force was ordered to march on Lisbon, Loison sent all of the Real Fuerte de la Concepción's artillery to Almeida, and ordered our fuerte's two northernmost bastions to be destroyed, so as to prevent anyone (such as the Spanish) from using the fort in the future.

|

France's Army of Portugal found itself in an inextractable position by August of 1808, and the Convention of Citra was signed on August 30, which made arrangements for the Royal Navy to evacuate the defeated French Army from Portugal. The British Army occupied the Real Fuerte de la Concepción, and recognized it to be exactly what it was intended to be: A great place from whence to launch an attack on Almeida.

Having had one's army defeated and transported from the field by one's enemy may have discouraged any normal person, but Napoleon was no normal person: He was determined to have Portugal.

|

|

There are many such inspirational scenes from the interior of the fuerte online...as the Real Fuerte de la Concepción presently operates as a hotel! There are many such inspirational scenes from the interior of the fuerte online...as the Real Fuerte de la Concepción presently operates as a hotel! |

|

Which begs the question, what was so great about Portugal, and why were the Spanish and French so hell-bent on possessing it? It brings to mind the British and Americans inexplicably squabbling over Canada for such a long period of time. Canada?! In that case, America likely felt that it's right there, and here we are galloping across this continent and claiming everything, sooooo...while Britain was all, our empire, period. I suspect that Spain wanted Portugal for much the same reason that America wanted Canada...it's right there, plus they'd had it before and it seemed like it was theirs. And Napoleon just plain wanted everything, at least everything physically attached to Europe. And several other things.

|

A firing gallery in the fuerte. A firing gallery in the fuerte. |

|

British Captain John Fox Burgoyne (1782-1871) of the Royal Engineers (son of the General John Burgoyne (1722-1792) who surrendered his force to the Americans at the Battle of Saratoga (October 17, 1777)) oversaw the refortification of the Real Fuerte de la Concepción in 1810.

The northern bastions that had been semi-destroyed by the retreating French were repaired and rubble was removed...but the greatest effort in this process seems to have been the placement of tons and tons of gunpowder so that the fuerte could be destroyed when and if it looked like the French might get the fort back into their clutches.

|

|

Is it just me, or does everybody seem more concerned with what they'll do when they're forced to abandon this fuerte, than how they'll fight to keep this fuerte? Could it be that the Real Fuerte de la Concepción was designed to act solely as a marshaling point for attacks into Portugal, and, despite its stellar configuration, was never intended to defend itself against a major effort by a large army?

|

Ciudad Rodrigo is yet another Spanish fortified city, about sixteen miles southwest of the Real Fuerte de la Concepción. The French began their next foray into Portugal with a siege of this particular ciudad, from April 'til July of 1810. The Spanish garrison therein put up a good fight, and though they were ultimately defeated, they delayed the French invasion of Portugal for a month...but first the French had to get past the Real Fuerte de la Concepción.

Which would prove to be no problem whatsoever, because the British and Portuguese troops manning our fuerte were more than ready to light the fuse on their self-destruct machine and skedaddle! The big boom came at 4:45am on July 21, catching several of the advancing French dragoons with shrapnel...but the boom was nowhere as big as it should have been.

|

|

Ciudad Rodrigo, Spain, which is surrounded by starforty defenses. Does that make it a starfort? No, in my opinion that makes it a fortified town. But, ask me again in a few years and my opinion may have changed. Ciudad Rodrigo, Spain, which is surrounded by starforty defenses. Does that make it a starfort? No, in my opinion that makes it a fortified town. But, ask me again in a few years and my opinion may have changed. |

|

Because only one of the four charges had detonated. Merci beaucoup for the slightly-damaged starfort, said the French, though a series of smaller explosions along with the one big blast had done a pretty good job of messing up our fuerte. Messed up or not, the French used the Real Fuerte de la Concepción as a staging point to attack, you guessed it, the Fortress of Almeida.

They also gussied our fuerte up to serve as the headquarters for the generals in charge of the upcoming invasion, most notably Marshal André Masséna (1758-1817). Four baking ovens and a detail of bakers were installed in the Real Fuerte de la Concepción so as to cater to the Marshal's culinary needs. How many baked confections Masséna might have consumed whilst in the fuerte is unknown, but it can't have been too many, as he was only there for the ten days it took his Army of Portugal to capture Almeida. |

Ever wanted to spend the night in a casemate? If I've learned anything from my study of starforts, it's that casemate living wasn't all it was cracked up to be...but this kind of casemate experience looks much more pleasant than one might have had in 1810. Ever wanted to spend the night in a casemate? If I've learned anything from my study of starforts, it's that casemate living wasn't all it was cracked up to be...but this kind of casemate experience looks much more pleasant than one might have had in 1810. |

|

Masséna and his Army of Portugal headed for Lisbon, but the delays, tactical withdrawals and partially-exploding starforts arranged by British commander Arthur Wellesley, the First Duke of Wellington (1769-1852) gave the British and Portuguese time to complete the Lines of Torres Vedras. This massive line of forts and other defenses was sufficient to prevent the French from taking Lisbon.

A small French garrison was left at the Real Fuerte de la Concepción, but they abandoned the fuerte in the Spring of 1811 as the British and Portuguese, who were pushing the French out of Portugal, approached in force. This was the last time that the possession of our fuerte was contested, and not once did anyone even attempt to fight to keep it. |

|

Today the Real Fuerte de la Concepción operates as a really quite attractive-looking hotel! Seven stone buildings contain a bar, three dining rooms, a "summer and winter terrace," several lounges and meeting rooms...and there are fourteen "fully-equipped Junior Suites," located in the fuerte's casemates along its curtain walls. A visitor to this hotel in 2013 reports being shown a "listening well," in which soldiers would crouch, listening for the telltale sound of besieging enemies digging mines.

Many thanks to determined starfort-finder Nico Pfeifler, who reminded us of the existence of the Real Fuerte de la Concepción! I had started a page on this fort in 2013, but got distracted by a shiny object and forgot about it, as I have the attention span of a small bird.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|