|

Fort at Coteau du Lac

Coteau du Lac, Québec, Canada

|

|

|

Constructed: 1779-1780, 1813

Used by: Great Britain

Conflicts in which it participated:

None

|

Canals are cool. They're state infrastructure which, in a broad sense, are what starforts are as well. America's most famous lock canal is the Erie Canal, which was constructed from 1817 to 1825, and by providing a cheap means of transporting goods into the hinterlands, solidified New York City's economic and cultural advantage over other port cities on America's east coast. The Erie was not, however, the first such canal in North America. |

|

|

|

The Saint Lawrence River connects the Atlantic Ocean with the Great Lakes, and is pretty much the reason that Canadian cities like Montreal, Kingston and Québec City exist where they do. While the river does indeed connect these bodies of water, one could not simply leap aboard a boat in the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and sail placidly down to Lake Ontario: The Lachine Rapids at Montreal and the rapids at Coteau du Lac (Coast of the Lake) to Montreal's southwest made for the irritating necessity of portage.

Portage is French for "pick up and carry all of the stuff you wish you could transport by water, including your boat." Nothing but the flattest-bottomed boats, piloted by the steeliest-nerved individuals, could make their way through these rapids, so everything being delivered from the Atlantic to the Great Lakes via the St. Lawrence needed to be carried by humans on land for at least some portion of the trip. Had something like a rail system or even decent roads existed in tandem with the necessity of the portage, then this might not have been much of a problem...but this was undeveloped territory at the far reaches of France's, and then England's, empire.

|

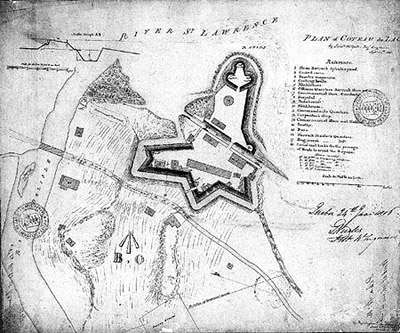

The Fort at Coteau du Lac in 1815, as drawn by Lieutenant Walpole of the British Army. The Fort at Coteau du Lac in 1815, as drawn by Lieutenant Walpole of the British Army. |

|

Though the English established the first European colony in what is now Canada on Newfoundland in 1583, the French did them one better by colonizing the mainland, at Port Royal in 1603 and Québec City (home of the Citadelle de Québec) in 1608. France developed itself quite an impressive possession of Canada, until it had to go and lose the Seven Years' War (1756-1763), which defeat passed the entire colony to England. Québec in particular was far more French in practice than the rest of Canada, and England had the good sense to pass the Quebec Act in 1774, which gave Québec a level of autonomy and self-administration that was unusual amongst English colonies at the time. Well done, King George III (1738-1820)! Québec is still a weird and delightful amalgamation of France and America (and I suppose Canada) today. |

|

However wisely England managed its Canadian colony, it still had the United States to deal with. Most of the Canadian places and things that England wished to keep secure were scant miles from the border with a belligerent new USA, and keeping its military posts close to that border effectively supplied and manned was a logistical nightmare. Enter the canal!

|

The Chinese had been building canals for the purpose of transport as early as the 8th century BC, and the Greeks were the first to utilize the lock system in the 3rd century BC. The first Western European canal was the Fossa Carolina, created in the 8th century AD in Bavaria at the behest of Charlemagne (742-814). Clearly, this was a civilized society's solution to transport issues such as that confronting the British at Coteau du Lac!

Great Britain's military outposts along Canada's southern border were exquisitely vulnerable during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). Québec's Governor, Sir Frederick Haldiman (1718-1791), ordered that a canal be dug to skirt the rapids at Coteau du Lac in 1779, and put in charge of this project was Captain William Twiss (1745-1827) of the Royal Engineers.

|

|

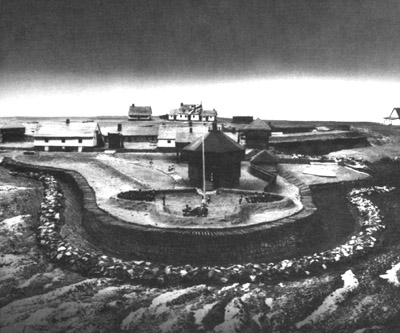

What is probably a creative photograph of a diorama of our fort, although it may well have been an 1815 photograph taken from the platform of an 1815 drone. What is probably a creative photograph of a diorama of our fort, although it may well have been an 1815 photograph taken from the platform of an 1815 drone. |

|

Captain Twiss would go on to be the party most repsonsible for England's array of Martello Towers during the Napoleonic Wars, but in the meantime, the actual canal-digging in this case was handled by the King's Royal Regiment of New York, a loyalist unit that had, two years previously, participated in the Siege of Fort Stanwix. At the same time that this arduous digging was taking place, fortifications were built to protect this vital strategic asset. Two blockhouses were initially constructed to protect the canal at this location, alongside a couple of three-story warehouses, in which various supplies were stored for the 6,000 troops stationed at Canada's outposts on the Great Lakes. The canal was complete in 1780, and around 900 batteaux (shallow-draft, flat-bottomed boats), filled with supplies for those troops, traversed the Coteau du Lac Canal that year. When completed, the system had three locks, compensating for a drop of about six and a half feet over the length of the canal. |

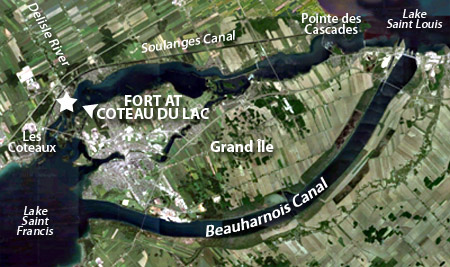

Canals, canals, canals. What *I* thought was the Coteau du Lac Canal is actually the Soulanges Canal, which opened in 1899 to replace the first version of the Beauharnois Canal, which canal fumed and plotted until it enlarged itself and reopened in 1958, whereupon the Soulanges was rendered tragically obsolete. Canals, canals, canals. What *I* thought was the Coteau du Lac Canal is actually the Soulanges Canal, which opened in 1899 to replace the first version of the Beauharnois Canal, which canal fumed and plotted until it enlarged itself and reopened in 1958, whereupon the Soulanges was rendered tragically obsolete. |

|

When viewed in context with the canal it was apparently built to defend, the Fort at Coteau du Lac seems to be sited at a counterintuitive spot. Why not defend the places where the canal is connected to the Saint Lawrence, at the Pointe des Cascades to the east, and Les Coteaux to the west?

Our fort was built where the little Delisle River meets the Saint Lawrence: Just at the northern extent of the rapids at Coteau du Lac. What looks like the canal we're talking about stretches for about 14 miles along the northern bank of the Saint Lawrence, but...Gotcha! That's not the Coteau du Lac Canal!

|

|

As it turns out, though the canal of our current interest was the first such canal in North America, and did the job it needed to do at the time, it was shrimpy. When it opened in 1780, the Coteau du Lac Canal was just shy of six feet wide, 30 inches deep and maybe 350 feet long, which, I think we can all agree without irony, isn't very long for a canal. See that diagonal slash through the center of the fort as it is seen at the top of the page? That is the original Coteau du Lac Canal.

Diminutive though it may well have been, the canal worked for its intended purpose...so much so that, within another three years, three more canals had been dug in the vicinity. As is made clear by the map above, the area has since become a veritable battleground of warring canals, each forever angling to supersede the others in prominence.

|

On June 19, 1812, US President James Madison (1751-1836) announced that the United States had declared war on Great Britain. This drastic step was undertaken for a variety of reasons, one of which may have been an earnest wish upon the part of the United States to invade and claim Canada. Moreso than ever, the weird little twist of British canals downriver from Montreal were in need of defense!

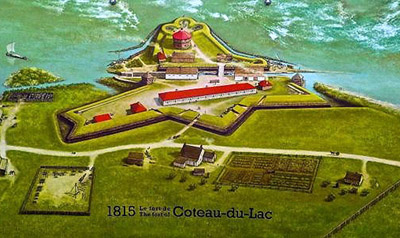

In 1813, the fortifications around the original Coteau du Lac Canal were extended to both sides of that waterway, with the "cloverleaf bastion" (a three-gun battery of 24-pounder guns) covering the river, blockhouse behind the battery and jagged starry earthworks that we see today. Though notionally ready for all comers, nobody ever attacked the Fort at Coteau du Lac.

|

|

The humble beginnings of canal technology in the New World: Blue dudes hacking at rock to make the shallow, narrow passage that was the Coteau du Lac Canal. The humble beginnings of canal technology in the New World: Blue dudes hacking at rock to make the shallow, narrow passage that was the Coteau du Lac Canal. |

|

Once the War of 1812 had been inconclusively concluded, our fort's garrison was drastically reduced, with likely just enough soldiers left to look menacing and ensure that boats passing through the canal continued to pay the required toll. The Coteau du Lac Canal was widened from 1814 to 1817 to make it useable by larger Durham boats, which had begun to show up on the Saint Lawrence in 1809.

|

The Fort at Coteau du Lac at the height of its powers, in 1815. The Fort at Coteau du Lac at the height of its powers, in 1815. |

|

The Fort at Coteau du Lac, unloved, crumbled around the still-operating canal. After having been utilized for various purposes other than that for which it had been built, the fort's blockhouse was burned to the ground in December of 1837, lest beavers capture it and put up a stout defense.

In 1843 the Beauharnois Canal, connecting Lake Saint Louis with Lake Saint Francis, completely bypassing all of the rapids nonsense, opened. The Coteau du Lac Canal had been replaced, and our fort was abandoned. |

|

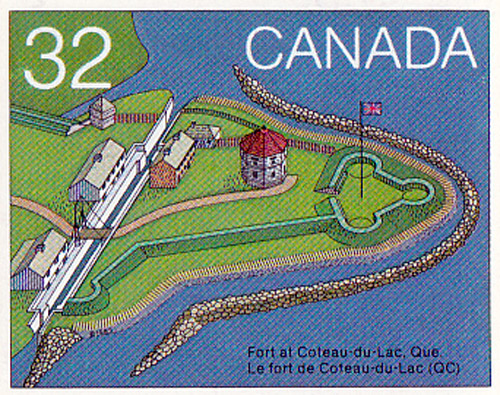

Today, the Fort at Coteau du Lac has been partially restored for visitors: The octaginal blockhouse has been rebuilt close to the foundations of the original, a 24-pounder gun is mounted on a period carriage in the cloverleaf bastion, and the foundations of the barracks building and others are plainly visible.

In 1983, the first ten of twenty Canadian forts were honored in the Forts Across Canada Series of stamps. In 1983, the first ten of twenty Canadian forts were honored in the Forts Across Canada Series of stamps.

The Fort at Coteau du Lac's stamp sits betwixt those of Lévis Fort No. 1 and Fort Beauséjour!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|