|

Fort de Roovere

Halsteren, Netherlands

|

|

|

Constructed: 1628

Used by: Netherlands

Conflicts in which it participated: Austrian Succession War

Also known as: Rovers Fort

|

The Netherlands has lots of water. Well, it has as much water as anyone can actually "have" water, but about half of the current Netherlands is under water, so I think we can all agree that, yes, that's a lot of water for any one nation to "have."

All this water has been both a blessing and a curse for the Netherlands: Countless navigable waterways helped the Dutch (as the Netherlandese were known) become a commercial and naval powerhouse, particularly after throwing off the wicked Habsburgian yoke; But imagine how much effort it would take to accomplish anything in a nation that's inundated with water.

|

|

|

|

In the late 16th century, the Netherlands began a process of reclaiming land (known as "polders") from the sea and lakes, which today amounts to over 15% of the country's land mass. But we're here to talk about starforts, not land masses, even if they are called polders.

What is today the Netherlands, Luxembourg and bits of Belgium were ruled by the Dukes of Burgundy from the mid-14th century until 1477, when those Dukes became extinct due to military adventure. The House of Valois-Burgundy, as those Dukes were known, became supplanted by the House of Habsburg, in the Holy Roman person of Maximilian I (1459-1519), Holy Roman Emperor. Max married into the Burgundy family and finagled his son into the House of Castile, which led to the Habsburg dynasty in Spain.

|

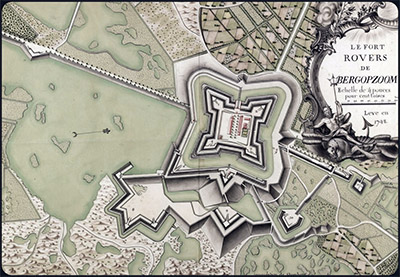

A 1629 map of the West Brabant Water Line. Click it, it's considerably larger. To the center right is "Rovers Fort," which is, in point of fact, the starfort of our current interest. A 1629 map of the West Brabant Water Line. Click it, it's considerably larger. To the center right is "Rovers Fort," which is, in point of fact, the starfort of our current interest. |

|

All of which seems as though it would have been far removed from the Netherlands, but I assure you that it was not. The Habsburgs in Spain ruled the Netherlands from afar, heavily taxing the Dutch while simultaneously being too far removed to offer much support or guidance.

The Spanish, being the Spanish, were also extremely strict about religious (Catholic) uniformity. |

|

Protestantism was gaining ground in the Netherlands, and the Inquisition, intimately familiar to all Monty Python devoteés, was used to keep "order." Spanish troops were also stationed in the Netherlands in plenty, and there seemed little in this bargain for the Dutch. These, and perhaps one or two other reasons, prompted the Dutch to fight for their freedom. This desire begat the Eighty Years' War (1568-1648), or Dutch War of Independence.

|

The Netherlands' countless waterways, leading deep into the country, were the source of the Netherlands' first real successes in the 80 Years' War. In the early years of the war, Dutch armies were no match for those of Fadrique Álvarez de Toledo, the 4th Duke of Alba (1537-1583), whom Spain's King Phillip II (1527-1598) had placed in charge of the Spanish effort...but hundreds of Dutch citizens who had been driven from their homes and country by the Spanish organized as the "Sea Beggars," essentially semi-piratical freedom fighters, which force kept an unceasing pressure on the Spaniards by raiding coastal targets and swooping away before a force could arrive to attack them.

|

|

Le Fort Rovers de BERGOPZOOM! circa 1628. Or maybe 1748. Le Fort Rovers de BERGOPZOOM! circa 1628. Or maybe 1748. |

|

The Dutch and Spanish had mutually exhausted themselves by 1609, and needed a break. Neither side was interested in ending this conflict, however, so they agreed on a truce, which would last for twelve years. Once things got rolling again, a failed attempt to besiege the Dutch fortress city of Bergen op Zoom convinced the Spanish of the futility of directly taking on Dutch starforts, and they concentrated instead on blockading the Dutch coast, intending to strangle the rebels in a financial fashion.

|

Fort de Roovere in 1751. With some cracks. Fort de Roovere in 1751. With some cracks. |

|

"Oh, so you don't like starforts, eh?" bellowed the Dutch, who built three of them to the south of Bergen op Zoom in a startlingly brief period in 1628. Fort Moermont, Fort Pinssen and Fort de Roovere were completed in 23 weeks of frantic activity, and Fort Henricus had been completed in 1626. These forts, stretching 11 miles from Steenbergen to Bergen op Zoom, comprised the West Brabant Waterline. This fortified line not only protected Bergen op Zoom's southern approaches, but Fort Henricus also stood at the tap of the Netherlands' secret weapon: Water! |

|

When a Spanish army approached, a sluice could be opened at Fort Henricus, and the surrounding countryside would be inundated with water from the River Vliet, rendering it impassable except by a fleet of shallow-draft barges, with which an attacking army would be unlikely to be supplied...at least the first time the Dutch played this soggy trick.

A Spanish attack on the adorable fortified city of Tholen in 1631 was derailed by strategic inundation, but in 1636 this lesson had been taken to heart, and the Spaniards were prepared with barges when they attacked Steenbergen. This quick Spanish thinking ultimately wasn't quick enough, as the quicker-thinking Dutch managed to throw up a series of new redoubts which foiled the dastardly Spanish scheme.

|

The West Brabant Waterline did its job, and the 80 Years' War ended in 1648 with Bergen op Zoom unsullied by the Spanish, and the Dutch Republic a new and startling presence in western Europe. Other western European nations had benefited greatly from the lengthy discomfiture of the Dutch, and as Amsterdam resumed its place as Europe's preeminent commercial shipping destination, and increased Dutch activity overseas interfered with many Portuguese colonial claims, the new Dutch Republic found it necessary to solidify its defenses.

Enter Menno van Coehoorn (1641-1704). An inventor and energetic military innovator, van Coehoorn became known as "the Dutch Vauban."

|

|

The eastern side of Fort de Roovere, which features the Moses Bridge (see below), has been reconstructed to a greater extent than its western side. The view we see here, I'm cautiously certain, is looking across the north of the fort from west to east, along the courtin, or curtain wall. |

|

Sébastien Le Prestre de Vauban (1633-1707) was, as we all know, the Father of the Starfort. As French King Louis XIV (1638-1715)'s chief military engineer, over a period of 40 years Vauban directed the construction of 37 French starforts, and waved his magic wand of starfortery over 300 cities, upgrading their defenses. Though contemporaries in the Brotherhood of the Starfort, van Coehoorn and Vauban fought on opposing sides in the War of the Grand Alliance (1688-1697), in which France was at war with pretty much everybody who wasn't France.

|

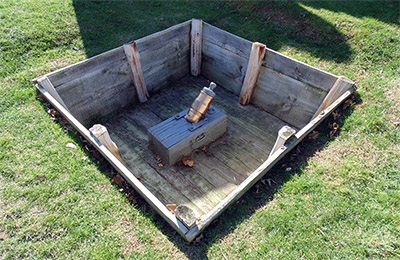

A Coehorn Mortar at Fort Ligonier in Pennsylvania, USA. This two-man-portable mortar, invented by Menno van Coehoorn in 1674, fired a 4.5" shell at a 45° angle, and was handy enough for the British and Americans to produce and utilize similar mortars in various sizes through the mid-19th century. Check out Starforts.com's Visit to Fort Ligonier page for more pix of shiny British brass artillery! A Coehorn Mortar at Fort Ligonier in Pennsylvania, USA. This two-man-portable mortar, invented by Menno van Coehoorn in 1674, fired a 4.5" shell at a 45° angle, and was handy enough for the British and Americans to produce and utilize similar mortars in various sizes through the mid-19th century. Check out Starforts.com's Visit to Fort Ligonier page for more pix of shiny British brass artillery! |

|

In this instance they essentially broke even: Van Coehoorn directed the fortification of, and personally defended, the city of Namur when the French came a-siegein' in 1692. The French, directed by Vauban, managed to force the city to capitulate after a 36-day siege...but then Van Coehoorn and the Dutch returned in 1695 and took the city back from the French, despite Vauban having sprinkled his magic starfort dust o'er the city's defenses in the interim. We would call that a draw.

But I digress. More to the point of this page, Van Coehoorn applied his talent to Fort de Roovere in 1727, adding a "line wall" to the south side of the fort. He also made extensive improvements to the fortifications of Bergen op Zoom at this time, whose stellar defenses are considered his masterwork. |

|

Unfortunately for both Bergen op Zoom and Van Coehoorn's legacy, a kerfuffle over a royal succession amongst those troublesome Habsburgs was used as an excuse by most of the major European nations to have another war, which in this case was the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748). This conflict brought the French back to the Netherlands, where they besieged Fort de Roovere in 1747, as part of an operation against good ole masterwork Bergen op Zoom.

|

As pointy and exciting as were Van Coehoorn's defenses of Bergen op Zoom, the fortification lacked a second line of defense and any sort of citadel that could be held in a defensive fight. After a siege lasting 70 days, the city surrendered and was comprehensively sacked, its garrison slaughtered. The siege of Fort de Roove was discontinued as pointless.

Somebody thought that Bergen op Zoom's extended defenses were still worthy of upkeep in the 1780's, because improvements were made to Fort de Roovere in 1784: A "main wall" was constructed on the fort's north side. It's difficult to surmise what this "main wall" looked like, as all that is now to the north of our fort are...trees.

|

|

Fort de Roove's Moses Bridge, built in the early 2010's by the Friends of the Fort de Roovere Foundation, grants access to the fort through its eastern curtain wall. |

|

Bergen op Zoom was once again besieged in 1814, this time by the British, with the French behind the city's walls. This took place towards the end of the Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815), when the armies of Napoleon (1769-1821) were being ground down and in the process of slinking back toward France...but the tail of the French army still had plenty of sting left in it. Bergen op Zoom's 2,700-man French garrison was supported by the city's populace, who helped to see off the 4,000-man British attack. The starfort of our current interest appears to have not been involved in this fracas.

|

Fort de Roovere's southern bastion. Bliss. |

|

Once Napoleon was safely in his cage on the island of Saint Helena, the world agreed that the concept of war was officially passé, and so Fort de Roovere was decommissioned in 1816.

The surrounding countryside said, "why yes, we would be more than happy to reclaim this location," and set about overgrowing and otherwise undoing everything that man had wrought in the shape of Fort de Roovere.

...until the 21st century, as in 2000 the Friends of Fort Roovere Foundation leapt into being. Other similar entities, such as the Friends of the West Brabant Waterline Foundation and the Menno van Coehoorn Foundation, banded together and initiated a plan to restore Fort de Roovere. |

|

This process began in earnest in 2010, when much vegetation was removed from the fort, and its moat and canals deepened. Access through the moat was granted by the Moses Bridge, an innovative design that appears to "split the water." Today what appears to be about half of Fort de Roove's walls have been restored. Is this an ongoing process? One hopes so, but it's difficult to tell with certainty from available sources. Let us know, Dutchmen (or -women)!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|