|

Drottningskärs Kastell

Drottningskär, Sweden

|

|

|

Constructed: 1680-1750

Used by: Sweden

Conflicts in which it participated:

Russo-Swedish War of 1788-1790

Napoleonic Wars

Also known as: The Gray Lice That

Destroyed Catherine the Great's Plans

|

As much as any war can be considered good, the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648) was a good one for Sweden. Under the leadership of Kings Gustavas Adolphus (1594-1632), Charles X Gustav (1622-1660) and Charles XI (1655-1697), Sweden went from being "a poor and scarcely populated country on the fringe of European civilization" to an empire that commanded most of the lands bordering the Baltic Sea.

One of the Baltic nations Sweden had not conquered, however, was Denmark. Sweden's main naval base had naturally been at Stockholm...but in 1679 Charles XI ordered the construction of a new base, which would be closer to Denmark: The War City of Karlskrona.

|

|

|

|

Sweden has been known as a seafaring nation for as long as people have been writing down their observations, and much of its coastline is a nightmare of teeny fractured little islands. Defending a coastal facility from an enemy's ships when there are 370 different route options would seem a daunting task, and there are probably way more fortifications, star- and otherwise, tucked away in unlikely Swedish places than I will ever find, but Sweden seemed to know what it was doing when it set up Karlskrona, the construction of which began in 1680. In addition to being closer to Denmark, Karlskrona (named for the king and Landskrona, home of the lovely Landskrona Citadel...which is as stellar a starfort as ever there was, but why was a naval base 130 miles away from it named after it?!), being more southernly than Stockholm (practically equatorial by Swedish standards), had the added benefit of not being iced in for much of the year. |

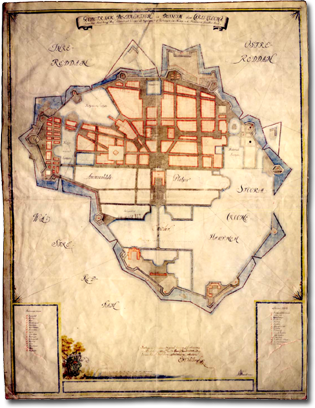

Karlskrona in 1683, by Erik Dahlberg and Karl Magnus Stuart. Karlskrona in 1683, by Erik Dahlberg and Karl Magnus Stuart. |

|

Karlskrona would of course need protection from seaborne enemies, which of course meant fortification, which of course meant starforts...or at least ˙a˙ starfort, which is what we're talking about here. Swedish military engineer Erik Dahlbergh (1625-1703) was assigned to build a fort on the island of Aspö to command the most likely sea route into the Blekinge archipelago (and thus to Karlskrona), through the 130-yard-wide strait betwixt Aspö and Tjurkö, off of whose western shore would be another fortification (of which we will learn shortly), thus forcing any attacking ships to pass through an unsurvivable gauntlet of fire.

Our starfort was named for the town of Drottningskär, next to which 'twas built. This was, and still is, a tiny town, with a population of 305 in 2005.

Dahlberg, who also had a hand in the creation of the map to the left, was excited as plans for Drottningskärs Kastell took shape: "there would hardly be a more beautiful SiööCastel in the whole of Europe," he reported, and it was hard to argue with him, seeing as nobody knew what a SiööCastel was.

|

|

Drottningskärs Kastell's primary feature is its donjon, the three-story rectangular structure that dominates its interior. Guns were mounted in the donjon (one assumes there are casemates within), and the fort was designed for a total of 44 guns to be able to bear on the strait.

|

Donjons are very nice, but you need bastions and curtain walls to be a starfort. The four bastions surrounding the donjon were named after Swedish queens: Kristina ((1626-1689), Queen of Sweden 1632- 1654), Hedvig (Hedvig Eleonora of Holstein-Gottorp (1636-1715), wife of King Charles X Gustav and regent during the minorities of Charles XI and Charles XII), Maria (Maria Eleonora of Brandenburg (1599-1655), wife of King Gustavus Adolphus) and Ulrika (Ulrika Eleonora of Denmark (1656-1693), wife of King Charles XI).

Unfortunately I couldn't tell you which is which, but naming bastions after queens is a nice touch...a definite improvement over Spain and Portugal's tendency to name theirs for lengthily-titled saints*.

|

|

Drottningskärs Kastel's donjon, from its northeastern bastion: Kristina, Hedvig, Maria or Ulrika? I'd like to think it's Hedvig. Drottningskärs Kastel's donjon, from its northeastern bastion: Kristina, Hedvig, Maria or Ulrika? I'd like to think it's Hedvig. |

|

You will note in the picture at the top of this page that there is no curtain wall connecting the rear bastions, because the donjon comprises the entire rear end of the starfort. This made sense if one were only expecting to be politely attacked from the front, but enemies were occasionally wily enough to approach a strongpoint from the rear, so this issue was addressed in the 1730's with the addition of the absolutely spectacular ravelin, at the tippytop of this page's main image: A ravelin may or may not have been independently armed (as is the complicated ravelin at Fort McHenry), but even unarmed, it served to prevent direct fire from being applied to the curtain wall, gate or donjon that it protects.

|

Kungsholms Fort, anchoring the eastern side of the strait in question. Kungsholms Fort, anchoring the eastern side of the strait in question. |

|

Drot to the left, Kungs to the right. And not a moment's rest in between. Drot to the left, Kungs to the right. And not a moment's rest in between. |

|

In 1788, Swedish King Gustav III (1746-1792) was not particularly favored by his subjects. He reasoned that a brief, splendid little war would make everyone like him, so he sent the Swedish Open Sea Fleet to attack St. Petersburg (where, he surely hoped, it might get a crack at the magnificent Peter and Paul Fortress) in June of 1788. Though unsuccessful in its goal of capturing St. Petersburg and overthrowing Russian Czarina Catherine the Great (1729-1796), Sweden's fleet did manage to prevent the Russian Navy from sailing against the wicked Ottomans, with whom Russia was presently at war (as was frequently the case)...because no Russian Navy is going to leave St. Petersburg to be bashed by the Swedes. Navies sailed back and forth and flung shot at one another in the Baltic, and eventually a Russian fleet was sent to destroy Sweden's naval base at Karlskrona. Parked to the south of the entrance to Blekinge archipelago, the Russian Admiral and his officers peered through their telescopes at Drottningskärs Kastell to the west, then turned to Kungsholms Fort to the east...and determined that today was not a good day to die. |

The Russian fleet returned home and its Admiral reported to Catherine the Great that Karlskrona was unassailable, due to the Swedes' mastery of the art of coastal fortification. Infuriated, Catherine paid Drottningskärs Kastell the highest compliment possible from an enemy, when she referred to the fort in her diary as "...the gray lice that destroyed my plans." Judging by the satellite imagery I would say that Drottningskärs Kastell's color could more accurately be described as camel, but it seems reasonable to assume that Catherine would have been looking at a black & white version of Google Maps, it being the 18th century.

The Russo-Swedish War (1788-1790) was ultimately inconsequential, as befits a war initiated for less than 100% certified noble purposes. Gustav III did not receive the spike in approval ratings that he had envisioned, and was assassinated, at the behest of Sweden's nobles, at a masquerade ball at Stockholm's Royal Opera House in 1792.

By the end of the 18th century, Europe's big problem became Revolutionary France. France's anti-monarchial meltdown morphed into Napoleon (1769-1821) finding within himself the imperial will to conquer the known universe, and by 1801 the fightin' British Empire was concerned that Denmark would hand its navy over to the Wee Tyrant. The Royal Navy's Vice Admiral of the Blue and Future Most Heroic Personage Imaginable Horatio Nelson (1758-1805) was dispatched to Copenhagen where, on April 2, 1801, his fleet fought it out with the Danes. Both fleets were severely damaged, but Denmark's Navy had effectively been removed from the field of play.

|

|

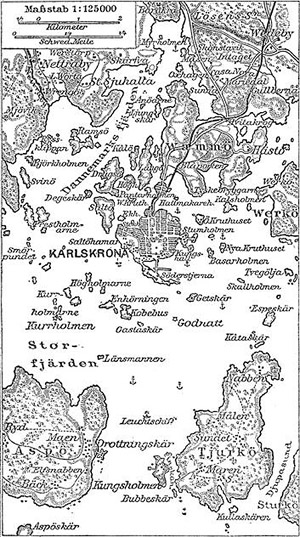

Karlskrona and its environs in 1888. I wish to point out that the island to Karlskrona's northeast appears to be called Wammö, which is the best possible name for an island. Karlskrona and its environs in 1888. I wish to point out that the island to Karlskrona's northeast appears to be called Wammö, which is the best possible name for an island. |

|

Nelson had much the same concern for Sweden's Navy, anchored as always at Karlskrona: If left to its own devices, surely it was only a matter of time before Napoleon got his grubby mitts onto Sweden's warships. This was no far-fetched, whimsical idea: In the interest of re-establishing itself as a Baltic naval power, Sweden had allied itself with both France and Britain at various moments of convenience...and after destroying everything at Copenhagen, Nelson was clearly in a blowin'-stuff-up kinda mood.

|

Something colorful and festive occurring at Drottningskärs Kastell! Something colorful and festive occurring at Drottningskärs Kastell! |

|

Nelson found himself in the same situation as the Russian Navy a decade before, with his ships sitting off of the entrance to the archipelago of our current interest while he attempted to scope out the Royal Navy's chances of making it past Drottningskärs Kastell and Kungsholms Fort in one piece.

In the dark and fog of night, Nelson sent a launch into the strait to attempt to get a handle on the situation. Drottningskärs Kastell's commander, concerned that the powder in his guns was getting damp due to the fog, ordered a gun to fire blindly into the strait: This shot came perilously close to the British launch, whose commanding midshipman paddled back to his fleet and breathlessly reported, they got infrared!!

|

|

Okay, he probably didn't really say that, but it was reported that the Swedes apparently had some magical means of seeing through the fog and firing its guns with alarming accuracy. Seeing no reasonable means by which he could get his fleet past Karlskrona's mighty masonry sentinels, Nelson returned home.

|

Kungsholms Fort was extensively modernized in 1820, whereupon it took over the position of Main Defensive Facility at the Mouth of the Blekinge archipelago.

New rifled guns were mounted at Kungsholms Fort in the 1870's, at which time everybody realized that Drottningskärs Kastell was in excess of defensive requirements. Our starfort was disarmed at the end of the 1870's, and in 1895 was "removed from the defensive organization." What role it might have played in the defensive organization for the 20-odd years it was unarmed is anyone's guess.

The Karlskrona Kustartilleriregemente (Coastal Artillery Regiment) was established in 1902, and was based at Kungsholms Fort until 2000.

|

|

I believe it's been established that Kungsholms Fort is no starfort, but it does have this lovely little protected mini-harbor behind its walls, called the Rundhamnen. This wee harborlet and its gate were used daily into the 1890's, assumedly for supply runs and such. I believe it's been established that Kungsholms Fort is no starfort, but it does have this lovely little protected mini-harbor behind its walls, called the Rundhamnen. This wee harborlet and its gate were used daily into the 1890's, assumedly for supply runs and such. |

|

A battery of three 12cm guns were set up at Drottningskärs Kastell during the First World War (1914-1918) to enhance the previous-century-vintage armament at Kungsholms Fort. The Kastell's temporary coastal defense battery remained in place until 1929, when the guns were moved to a different location on Aspö.

Kungsholms Fort's Wikipedia page pronounces it to be "the world's oldest continuously fortified military facility," but then goes on to say that it was not operational for at least a decade following the departure of the artillery regiment, which makes one wonder about the actual meaning of the Swedish word for "continuously." Reportedly as of 2020, Swedish naval conscripts are once again learning the art of war at Kungsholms Fort.

Both Drottningskärs Kastell and Kungsholms Fort were recognized as State Monuments in January of 1935. The Kastell's present owner, the poetically-named Swedish Property Agency, has been restoring the fort since 1993. In 2008 it completed a wooden bridge connecting the ravelin to the fort, and today Drottningskärs Kastell is open to visitors, with the Kaffee & Glass restaurant in the donjon providing...well, coffee served in glasses, I guess.

|

* "The Holy Bastion of the Most Prestigious and Illuminative not to mention Majestically Magnificent Saint Adolphus' Loving Pet Dog that sat next to the Potted Plant on the Fantastically Decorated Front Porch needs more ammunition immediately!"

"...which bastion needs more ammunition?!"

(Sigh) "I said the Holy Bastion of the Most Prestigious and Illuminative not to mention Majestically Magnificent...ah crap never mind, it's been overrun."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|