|

Fort Duquesne

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, USA

|

|

|

Constructed: 1754

Used by: France

Conflict in which it participated:

French & Indian War

|

It's a good thing that one doesn't pronounce the last few letters in many French words, because I would have no idea how to pronounce Duquesne otherwise. Fortunately, you just have to read it, not pronounce it.

In the mid-18th century, the North American continent was both dearly desired and viciously fought over by France and Great Britain. And Spain, but they don't figure into this story. |

|

|

|

Both sides did their best to strike a balance with North America's local inhabitants: France and Great Britain wanted to enlist the help of the various Indian tribes to slaughter the opposing Europeans, but then wished for them to disappear. The ultimate expression of this struggle came as the French and Indian War (1754-1763), which is how we in the western hemisphere refer to the Seven Years' War (1754-1763).

|

A dinky, tiny model of Fort Duquesne at Fort Pitt's visitor's center. |

|

Concerned with a series of forts that the French started building in the early 1750's just south of Lake Erie in what is today the northwestern tip of Pennsylvania (what was then known as Ohio Country), in January of 1754 Lieutenant Governor of the Virginia Colony, Robert Dinwiddie (1693-1770), sent a force of Virginians to the point where the Allegheny and Monongahela Rivers meet, to build a fort and thus deny this magical spot to the French.

On April 18, a much larger French force came upon the Virginians, who were in the process of building what would have been Fort Prince George. The Virginians immediately surrendered, and their paltry fort was knocked down, making way for Fort Duquesne. |

|

|

Named for Michel-Ange Duquesne de Menneville (1700-1778), Governor-General of New France, Fort Duquesne enjoyed an illustrious but brief career. Built on swampy, low ground that was prone to flooding and must have been an exquisitely unpleasant post, Fort Duquesne did successfully repel two British attacks during the French & Indian War.

|

The first attack came in the summer of 1755, and would result in one of Great Britain's worst military defeats of the 18th century. 2100 men (1300 in the vanguard, with the remaining 800 back with the baggage train) led by General Edward Braddock (1695-1755) slowly hacked their way through the wilderness in a vast, irresistible column, determined to smite the 1000 or so French and Indians a mighty blow and deprive them of Fort Duquesne.

Riding majestically as part of this expedition was a young Lieutenant named George Washington (1732-1799), who would go on to do various significant American things, such as throw objects a physically impossible distance across the Delaware River.

|

|

Today's flat yet still intimidatingly sharp east bastion of Fort Duquesne. Today's flat yet still intimidatingly sharp east bastion of Fort Duquesne. |

|

Braddock, inexperienced in the ways of war on this new battlefield, fully expected his enemies to line up in a conveniently exposed fashion and allow themselves to be systematically slaughtered by the scientific application of cannon and musket fire, as was the popular style of warfare in Europe. The infinitely wise and heroically infallible Washington warned Braddock of this folly, but Braddock responded with a bellicose and foolish "Harrumph!" Hubris, thy name is Braddock.

On July 9, 1755, Braddock's force crossed the Monongahela River about 10 miles south of Fort Duquesne. The French and Indians were rushing towards the river to set up an ambush, and the two forces blundered into each other. This resulted in what is known as a "meeting engagement," which is what the military calls it when two forces blunder into each other.

The following Battle of the Monongahela consisted of the French and Indians hiding behind things and shooting down British troops that were desperately concerned with maintaining their pointless, pretty paradeground formations. The British lost around 800 of the 1300 men Braddock led into the battle, including Braddock himself, who was shot off his horse and reportedly borne from the field by Washington (in an heroic fashion). The combined French, Canadian and Indian troops lost fewer than 30 men.

|

A diorama of General John Forbes' victorious arrival at the semidestroyed Fort Duquesne, at Fort Ligonier's visitor's center. That would be Forbes there in the comfy-looking horse cart. |

|

A second English expedition was sent to secure the Ohio backcountry (which meant Fort Duquesne) at the beginning of 1758, under the command of General John Forbes (1707-1759). Determined not to repeat Braddock's mistakes, Forbes' army of 6000 men undertook a protected advance. This was the slow and cautious construction of a road through the wilderness, building supply depots and forts along the way to consolidate the advance.

Forbes' army included numerous women, children, artisans, sutlers servants and other hangers-on: It was a moving city, the second most populous collection of humanity in Pennsylvania at the time, smaller only than Philadelphia. |

|

|

The second attack deflected by Fort Duquesne was by 800 men led by General James Grant (1720-1806) in September of 1758. This was the vanguard of Forbes' "moving city," sent ahead to evaluate the strength of the fort. Like Braddock, Grant had no experience with fighting in the wilderness, a situation of which the French and their Indian allies were more than happy to take advantage, ambushing Grant before he even laid eyes on Fort Duquesne. The British suffered 342 killed, wounded or captured in this embarrassing exchange, one of the prisoners being Grant himself.

|

Though the garrison at Fort Duquesne had comported themselves most admirably, both of their victories over the British were gained relatively far from the fort's walls: They were under no illusions as to their ability to similarly surprise and annihilate the rest of Forbes' 6,000-man force. Fort Duquesne's commanding officer, Colonel François-Marie Le Marchand de Lignery (1703-1759) ordered the destruction of the fort on November 24, 1758 and scampered into the wilderness. Forbes and his men arrived the next day, danced many a happy jig, and took possession of the ramshackle remains of Fort Duquesne.

The British started construction on the much larger Fort Pitt in 1759, just a smidge to the east of what was left (which was probably not much) of Fort Duquesne. What little did remain of Fort Duquesne was swallowed up by the heavy industry that was built on this spot in the 19th century.

|

|

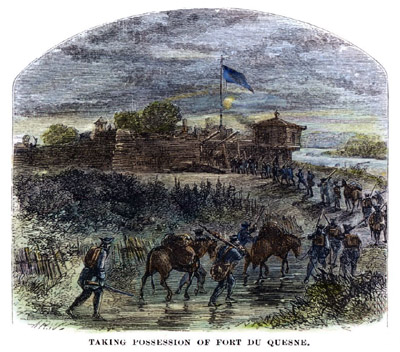

A 1758 painting of British troops taking possession of Fort Duquesne. The fort looks to be in pretty good shape for one that was supposedly "destroyed" by the departing French garrison! |

|

Today, a brick outline is all that visibly remains of the fort, ready and waiting to be stomped upon by visitors to Pittsburgh's Point State Park. In 2007 archaeologists found a stone and brick drain at the site, the depth of which suggests that it was used to drain an interior building of Fort Duquesne.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|