|

Fort Gadsden

Wewahitchka, Florida, USA

|

|

|

Constructed: 1814, 1818

Used by: Great Britain,

a Bunch of Black Folks and Indians,

United States of America

Conflict in which it participated:

First Seminole War

Also known as: British Fort, Negro Fort, Fort Apalachicola

|

The word Apalachicola makes one panic when one first sees it: I won't have to pronounce that word, surely? |

|

|

|

But the word figures prominently in the story of Fort Gadsden, so let's all say it together: Appa-latchi-cola! We can of course blame Native Americans for this word, as it was the name of a tribe which lived along a mighty river that flowed through what is today's Florida's panhandle. When white guys with parchment 'n' quill pens showed up to make the maps, they naturally named the river after the people who populated its banks. What's mostly exciting about the Apalachicola River today is that, if you drive over in from east to west, you're suddenly in the Central Time Zone, and you need to set your watch back an hour! Or forward an hour. Well, you definitely do one of those things.

|

Heading west o'er the Apalachicola River in 2018, utilizing the Trammell Bridge on Route 20. Steering is difficult when one is obsessively watching one's phone to see if it will immediately CLICK back one hour! Hint: It did not. Heading west o'er the Apalachicola River in 2018, utilizing the Trammell Bridge on Route 20. Steering is difficult when one is obsessively watching one's phone to see if it will immediately CLICK back one hour! Hint: It did not. |

|

More to the point from a strategic perspective, this wide, navigable river was a highway up into the wealthy plantations of Georgia...and it was such a natural boundary that it separated East and West Florida when the Spanish were in charge. Add a British interest in getting at those Georgia plantations, and all this means fortification!

When the Spanish owned La Florida, they identified a swell defensible spot at a bend about 14 miles inland on the River of Our Current Interest: A bluff rising about twelve feet above a swamp that almost completely surrounded it. They called it Loma de Buena Vista, "Hill With a Good View." The Spanish didn't particularly care about this river, however, as it didn't go anywhere of interest to them...so they left the loma unfortified. When persons who didn't speak Spanish discovered this spot, they called it Prospect Bluff. |

|

At the start of the 19th century Florida's panhandle was still almost entirely wilderness, yet proximate to America's southern states, whose agricultural economy was built on the backs of slaves. As a relatively unimportant part of the Spanish Empire, Florida's borders weren't aggressively patrolled by the authorities, nor was its colonial government interested in returning escaped slaves to their indignant masters. There were also a great many Native Americans who had been pushed out of their lands to the north again and again, who had coalesced in western Florida, tribes which included the Seminoles. Sharing a common enemy in the wicked white man, the Seminoles and escaped slaves got along relatively well, and set up their own plantation system...some of which operated on and around Prospect Bluff.

|

In 1804 a trading post was established at Prospect Bluff by John Forbes and Company, intended to supply plantations further up the river in Georgia. The War of 1812 (1812-1815) brought the Royal Navy to this trading post, at which time they looted the post and freed the slaves there employed.

What is the world's preeminent Empire to do when it feels the need to vanquish an upstart enemy nation, yet the size of that nation precludes the possibility of envelopement? One cozies up to that nation's misused classes and arms them, of course! Since there weren't many downtrodden Chinese laborers in Florida at the time, the English concentrated on the Indians and runaway slaves.

England had a long history of allying with certain Native American tribes, who may not have felt any great love for the British, but disiked the Americans even more, as those Americans were actively trying to extinguish the Indians.

|

|

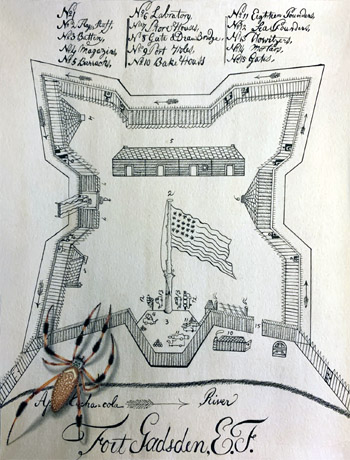

British Fort, from informational signing at Fort Gadsden. The section marked Powder Magazine in this drawing would be the undoing of Negro Fort. The Artillery Emplacement to the left along the river is the future location of Fort Gadsden. British Fort, from informational signing at Fort Gadsden. The section marked Powder Magazine in this drawing would be the undoing of Negro Fort. The Artillery Emplacement to the left along the river is the future location of Fort Gadsden. |

|

When the British were ejected from Pensacola in November of 1814 by US Army General and later-to-be-7th-US-President Andrew Jackson (1767-1845), events conspired to put 100 British officers and men at Prospect Bluff, amongst the Indians and black folks who were farming in the area. Commanded by Royal Marine Brevet Captain George Woodbine (1787-1833), the Brits wasted no time in recruiting and training the locals in the use of the Long Land Pattern Musket (the famous, and excruciatingly heavy, Brown Bess), in the interest of seeding armed discord in the Yankees' backyard. Some Native American tribes took more willingly to training and drills than others, a reminder that the many tribes represented many different cultures.

The British built a "formidable fort," whose formadibility did not extend to its name, which was British Fort: Any other commander would have just named the fort after himself, but apparently Woodbine was a self-depreciating sort. This fort was somewhere in the vicinity of 1600 feet long (east to west) and 800 feet wide...not enormous, but it dwarfed the future Fort Gadsden.

Woodbine's multihued force was planning to invade Georgia when, sadly, the war ended. The Royal Marines paid off their new recruits and withdrew, leaving behind a force much more able and willing to defend itself: A Corps of Colonial Marines, comprising 300 escaped slaves and 30 Seminole and Choctaw Indians, well supplied with arms and ordnance, now manned what became known as Negro Fort. This community became a beacon for disaffected slaves (all of them), a happenstance which did not endear it to slaveholders in nearby Georgia.

|

Warriors from Bondage by Jackson Walker, depicting the approach of the US Navy at Negro Fort on July 17, 1816. Warriors from Bondage by Jackson Walker, depicting the approach of the US Navy at Negro Fort on July 17, 1816. |

|

Word got around. Slaves from as far away as Virginia fled to Negro Fort...I'm in Virginia, and having made that trip myself, in a car, without angry white people chasing me, I'm here to tell you: Prospect Bluff is very far from Virginia. Proslavery newspapers in the United States wondered, "How long shall this evil, requiring immediate remedy, be permitted to exist?" In addition to the unspeakable evil of being a place where escaped slaves wished to go, the Apalachicola region was also a convenient hideyhole for bands of ne'er-do-wells that made their living by raiding Georgia's plantations and making off with whatever they could lay their hands upon.

To combat this scourge, in 1816 the United States built Fort Scott just over the Georgia border, where the Flint and Chattahoochee Rivers join to make the Apalachicola River. Supplying this fort overland would have been a nightmare, so the only reasonable means of supply was via the Apalachicola...which was commanded by Negro Fort.

On one occasion, troops from Negro Fort ambushed a watering party from one of those US supply ships that had unwisely come ashore near the fort. Three sailors were killed in this ambush, and one captured. |

|

The captured US sailor was reportedly burned alive by the garrison of Negro Fort. Unsporting, former Colonial Marines. By this point, the US Navy was understandably looking for an excuse to do away with Negro Fort. On April 27 of 1816, supply vessels were fired upon by the fort, and the Navy asked Andrew Jackson if they could pretty please deal with these unruly black folks. Jackson ordered Fort Scott's commander, General Edmund P. Gaines (1777-1849)(namesake of the stellar Fort Gaines, which guards the western side of the entrance to Mobile Bay: Gaines had also commanded Fort Erie in Ontario, after it had been captured by non-Ontarians), to destroy Negro Fort, which was now armed with 10 artillery pieces. The Colonial Marines had not been trained in the use of artillery, however, which became evident once US gunboats started trading shots with the fort on July 27. Prior to opening fire, however, Gaines requested the fort's surrender: Garçon, the leader of Negro Fort's defenders and a former Colonial Marine, declined, saying that he had orders from the British military to hold this post. |

After a few ranging shots, a single heated shot was fired from US Navy Gunboat No. 154, which entered Negro Fort's powder magazine, resulting in a massive explosion that could be heard 100 miles away in Pensacola. The precise number of the fort's defenders that were killed in the blast varies from source to source, but nearly all of the fort's garrison instantly died: Somewhere in the neighborhood of 300 men, women and children.

A number of Creek warriors had accompanied the US force in the attack on Negro Fort, their alliance secured by the promise of salvage. No doubt whooping with glee, the Creeks made off with 2500 muskets, 500 carbines, 400 pistols and 500 swords. Thank you, Heated Shot God!

|

|

Negro Fort goes kaboom. Its defenders had raised the Union Jack and a red flag, indicating there would be no quarter given: And they were correct, though not in the manner for which they had been hoping. Negro Fort goes kaboom. Its defenders had raised the Union Jack and a red flag, indicating there would be no quarter given: And they were correct, though not in the manner for which they had been hoping. |

|

Those black folks who had somehow managed to avoid being dismembered in the explosion were immediately dragged back into slavery, under the questionable (though perfectly reasonable to the parties (except the black parties) involved at the time) justification that Georgia slaveholders had owned their ancestors (?!). The trading post of John Forbes & co. was re-established at Prospect Bluff, but the area continued to be a destination for escaped slaves, whose grasp of current events may not have been the strongest.

Up to this point, the United States had been more or less respecting the fact that Spain owned Florida: They regularly passed through this Spanish land and had conducted military operations therein, but avoided any actual occupation of Western Florida. Recognizing the need to prevent Negro Fort from resuming its existence, the need to effectively police the area, and with an eye towards establishing a forward base for future forays into Florida, in 1818 Andrew Jackson ordered US Army Corps of Engineers Lieutenant James Gadsden (1788-1858) to build a fort on Prospect Bluff.

|

Lieutenant Christian Hutter was stationed at Fort Gadsden in 1820, and made this drawing, which is on display at the fort. This masterful copy was made for me by my daughter Tori, after she visited the fort nearly 200 years later. The gorgeous spider is a Trichonephila clavipes, better known as the Banana Spider, which is alarmingly and delightfully found in western Florida. Can we all agree that my daughter is awesome?! Lieutenant Christian Hutter was stationed at Fort Gadsden in 1820, and made this drawing, which is on display at the fort. This masterful copy was made for me by my daughter Tori, after she visited the fort nearly 200 years later. The gorgeous spider is a Trichonephila clavipes, better known as the Banana Spider, which is alarmingly and delightfully found in western Florida. Can we all agree that my daughter is awesome?! |

|

This fortification was initially a small octagonal earthwork fort with a magazine, built within the walls of Negro and/or British Fort, and named Fort Apalachicola. Jackson was pleased and ordered the fort's name changed to Fort Gadsden, but was less pleased when one of his aides visited the fort and described it as "...a temporary work, hastily erected, and of perishable materials, without constant repair, it could not last more than four or five years." Improvements were made, resulting in the snappy wood-and-earth starfort represented to the left.

Spain had finally had enough of Florida, and ceded it to the United States in May of 1821, as part of the Adams-Onís Treaty. And suddenly, there was no further need for a fortification at Prospect Bluff on the Apalachicola! With no nearby national border left to defend, Fort Gadsden, after all that trouble, was abandoned after less than three years of existence. The destruction of Negro Fort had arguably been the start of the Seminole Wars (1816-1858), a conflict in which Fort Gadsden is likely to have been utilized to a degree, but not garrisoned.

Whatever was left of Fort Gadsden was garrisoned by Confederate troops during the US Civil War (1861-1865), during which conflict it was used to protect communications betwixt plantations in Florida, Georgia and Alabama. The boys in gray were there from 1862 until July of 1863, when an outbreak of malaria forced them to abandon the post. |

|

Fort Gadsden Historic Site was opened in 1961, with a notable downplaying of the most historically significant period of Prospect Bluff's history, which was unquestionably that of Negro Fort. In 2016 the park was renamed Prospect Bluff Historic Sites...unfortunately, Florida's budgetary woes also forced the site to close that same year.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|