|

|

|

Fort McAllister was built in 1861 by the Confederacy on the Ogeechee River, in the expectation of protecting the rear approaches to the city of Savannah from the seaborne attentions of the Union ( Fort Pulaski and Fort James Jackson were guarding the front door). Forts built during the US Civil War were overwhelmingly of an earthwork nature: Earthwork forts, as compared to masonry forts, were easier, quicker and cheaper to build. Plus, folks were starting to have worrisome notions about the vulnerability of masonry forts to artillery, which was precisely what those forts had been designed to withstand! The technology of artillery had advanced past that of the masonry starfort. In addition to being fast 'n' cheap, earthwork fortifications proved to be more resistant to modern artillery. This was proven repeatedly at Fort McAllister, which resisted seven attacks by the US Navy over the three years of its existence with few casualties. |

|

|

Fort McAllister in December of 1864: An earthwork marvel! |

|

Fort McAllister: Weirdly-shaped, but effective. Fort McAllister: Weirdly-shaped, but effective. |

|

As was the case with other Confederate coastal fortifications, it took a landward approach, which was accomplished by General William Tecumseh Sherman and his merry, blue-clad band of marauders in December of 1864, to capture Fort McAllister. The fort of our current interest was the last thing standing betwixt Sherman and Savannah, and after the fort fell, the Confederacy abandoned the city.

To the best of our knowledge, few Civil War-era earthwork fortifications boasted their own hot shot furnace...but that is exactly what Fort McAllister possesses. It's a bit curious that such a furnace was included in this fort's design. Hot shot furnaces were standard issue at American coastal fortifications into the 1850's, but by the 1860's ironclad warships were all the rage, and heated shot was reluctantly admitted to be useless against such technological marvels. Confederate mastermind Robert E. Lee visited Fort McAllister in 1861 while it was under construction, and, being an engineer, made some suggestions to improve its strength. Was it his idea to build a hot shot furnace in an earthwork fort? As a Virginian I would like to think that we have Marse Robert to thank for this noble edifice.

Whomever was responsible for it, this is one strange, wonderful hot shot furnace. Virually all such furnaces at American forts were built from a standard, US Army kit, but just try to get the supplies of your choosing from the US Army when you're actively at war with it! Fort McAllister's shot furnace is a home-made affair, but seemingly no less effective than the standard issue: It's certainly more secure than a freestanding masonry shot furnace, in that it's protected by a huge mound of artillery-absorbant dirt. Manipulating the balls in and out of this furnace, however, must have been an unpleasant task indeed. While the part of the furnace into which the pre-hot shot would be deposited is relatively open to the air, the side whence the balls would be issued from the furnace practically requires one to walk into the furnace. |

|

|

To retrieve heated balls from Fort McAllister's shot furnace, one would have had to carry them from an open furnace, around a corner, and about a dozen steps through a masonry tunnel before reaching open air (actually a covered way, about another 25 or so steps). When that furnace was operating, in Georgia in the summertime, I would estimate the temperature within that confined space to have been around 3,250°. Celsius. Remember, however, that the Confederacy had a surfeit of dedicated laborers who were perfect for such tasks.

A slight concession was made to this situation, in that the furnace's firebox and ash pit were made accessible at the front. The system by which shot was heated in this manner wasn't as easy to slap together as it might appear: Heated air from the firebox had to be pulled around the iron shot before exiting through a flue, and it was easier to get these elements wrong than right. Who knows if Fort McAllister's shot furnace was as effective as a standard US one...but it did accomplish one thing that the vast majority of standard-issue American hot shot furnaces did not: It produced heated shot that was actually fired at an enemy ship! |

|

|

Facing into the fort. |

|

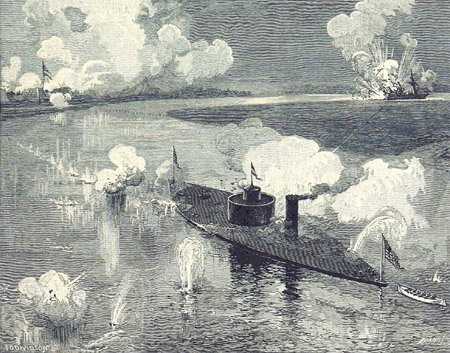

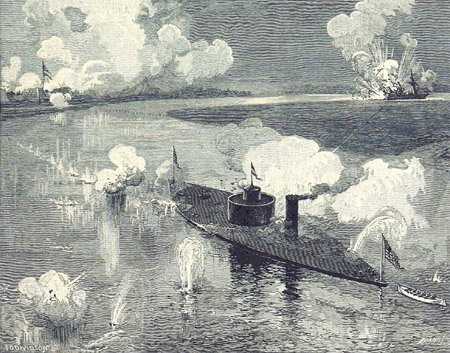

The USS Montauk takes out the CSS Rattlesnake while Fort McAllister, on the left, needlessly wastes heated shot. The USS Montauk takes out the CSS Rattlesnake while Fort McAllister, on the left, needlessly wastes heated shot. |

|

Unfortunately for the gunners at Fort McAllister, they were flinging heated shot at ironclads. The first four naval attacks on the fort involved the much more common wooden sailing warships of the age, but in each case those ships had the sense not to hang around for a slugging match with Fort McAllister. Information on exactly how many times Fort McAllister's hot shot furnace was used for its intended purpose is sketchy, but it seems that the four US Navy wooden vessels that attacked the fort in 1862 were in and out so swiftly that the shot furnace didn't have time to stoke up and get into play. Heated shot's big opportunity came along on January 27, 1863. The US Navy had some brand-new ironclad monitors it wished to use in Charleston Harbor to cow Fort Sumter into submission, but felt that these stumpy, unwieldy ships needed some sort of trial run. The decision was made to park them in front of Fort McAllister and essentially see how much of a beating they could take. As it happened, they could take plenty! The USS Montauk was the first of the ironclads to step into the breach. |

|

|

During the Montauk's first attack, she was hit thirteen times by the guns of Fort McAllister, but came away undamaged. The ironclad returned on February 1 for another go, and was hit 48 times...some of which were with heated shot. An enemy vessel just sitting there in range and trading fire gave Fort McAllister's hot shot furnace plenty of time to get into action, and that heated shot reportedly did do greater damage to the ironclad than dumb ole cold shot...but the "damage" consisted of slightly more visible dents in the Montauk's turret. As pretty much everyone had expected, heated shot was not a worthwhile projectile to use against an iron ship.

Combatants seldom kept any sort of records regarding the use of heated shot in battle. Maybe it was used far more frequently than we know today, but probably not. It was an incredible hassle to utilize, and while in theory it was a devastating weapon, it never really got much of a chance to do what it was intended to do, which was set wooden ships aflame and send them to the murky depths. The exchanges betwixt the Montauk and Fort McAllister's hot shot battery may represent the highest number of heated shots flung in anger during the Civil War. |

|

|

Insert balls here. |

|

Would you please click on any of the images on this page to see their full-sized counterpart, and read more of my brilliant observations about Fort McAllister's hot shot furnace. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|