|

Fort Jackson

Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana, USA

|

|

|

Constructed: 1822 - 1832

Used by: United States of America,

Confederate States of America

Conflict in which it participated:

US Civil War

|

The mighty Mississippi. The fourth longest river in the world, and stuff of American legend. So much of America's early history, commerce and transportation involved the Mississippi that I was extremely surprised when I couldn't find any starforts at its southernmost reaches, when I first followed Google Maps from the Ohio River at Cincinnati down to the Mississippi at the Gulf of Mexico, about a year ago. I eventually found Fort Pike and Fort Macomb guarding the entrances to Lake Pontchartrain to the east of New Orleans, which made me happy enough to stop looking for the fort I knew had to be on the greatest US river somewhere.

|

|

|

|

Anyway! Too late to make this long story short, but I spent some more time squinting at the Mississippi and found Fort Jackson. As you can plainly see.

We can thank the Spanish for the first fortification on the Mississippi. Spain was the first European power to investigate the Louisiana area in the early 16th century, but France did much more in the way of permanent settlement there, going so far as to claim all the land on both sides of the Mississippi, all the way from the Gulf of Mexico to Canada - Spain and Great Britain's reaction to this claim was, essentially, "whatever, France."

A variety of claimings and cedings of the Louisiana territory betwixt France, Spain and Great Britain due to wars of the 18th century briefly put Spain in nominal control of the region in the 1790's. The Spanish governor built a fort named San Felipe across the river from Fort Jackson's current location, from 1792 to 1795. 40 miles north of the mouth of the Mississippi and 80 miles south of New Orleans, 'twas constructed at a natural choke point: Plaquemines Bend.

By the time San Felipe was built, Acadians, folks of French descent who had settled in eastern parts of what was now becoming Canada and the United States, were being ejected from their settlements by the British. Many moved down to Louisiana, much of which was claimed by France. These Acadians magically transformed into Cajuns as the centuries rolled by. Louisiana at the beginning of the 19th century may have been technically ruled by Spain, but it had an enormous French presence, and by the time US President Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) made the Louisiana Purchase in 1804, he completed the transaction with Napoleon (1769-1821), whom, as we all know, was not Spanish.

|

Fort Jackson's beautiful casemates, rotting gently and refinedly through the centuries. Fort Jackson's beautiful casemates, rotting gently and refinedly through the centuries.

|

|

American troops moved into San Felipe, which they renamed Fort St. Philip, and began to make improvements in 1808. Please note that, while Fort St. Philip is germane to our interest in Fort Jackson, it was not a starfort, but a kind of uninspired pointy rectangle.

Whatever shape it may have been, Fort St. Philip proved its worthiness of its new nation by repelling a British fleet in January of 1815, during the War of 1812 (1812-1815). Five British ships bombarded the fort for nine days, firing over 1000 shells...but the ships did not make it past Fort St. Philip. Keeping the British ships at bay probably assisted the American cause in the Battle of New Orleans (January 8, 1815), which was the greatest US victory of the war.

|

|

This victory also made Andrew Jackson (1767-1845), who had commanded the defense of New Orleans, a pretty big deal. Jackson would be elected the seventh president of the United States in 1829, but immediately after the War of 1812 he was a national hero, dashing about saying and doing important things. One subject on which he expounded was the need for further fortification of the Mississippi.

While Fort St. Philip had performed admirably against the Royal Navy, it had been a near thing. Andrew Jackson's words were heeded, and in 1822 work was begun on Fort Jackson, which was completed in 1832. The fort's red brick walls were twenty feet thick and twenty feet high, with a circular citadel in the center, designed to protect 500 troops from the Spanish, French and/or British bombardment that everyone was sure would occur sooner or later. Once completed, Forts Jackson and St. Phillip dominated Plaquemines Bend where, in the age of sail, ships would have to slow to a crawl under the forts' 177 combined guns.

|

On January 8, 1861, local militia swooped down on Forts Jackson and St. Philip, capturing them from their small Federal garrisons, who were either so surprised or so outmatched that no fight was offered. Louisiana seceded from the Union on January 28, and the US Civil War began on April 11, 1861, with the attack on Fort Sumter in South Carolina.

Forts on coastlines were of course designed to withstand naval attack, and it was generally believed that such fortifications were invulnerable to shipborne guns at the outset of the war. The Federal success at the Battle of Port Royal in November of 1861, however, set lots of high-ranking men in blue a-stroking their whiskered chins in consideration of this basic truth.

On November 7, 1861, a Federal fleet pounded Fort Beauregard and Fort Walker into piles of sand and landed a force that captured Port Royal Sound in South Carolina, just a tad north of Savannah, Georgia. While Beauregard and Walker were standard slapdash Confederate forts (meaning that they were essentially earthworks), not the masonry marvels of post-War of 1812 US starfortery, their relatively easy defeat made Federal war planners reconsider their strategic options.

|

|

Though Fort Jackson was designed to mount 93 guns, during the battle it had only 69 guns ready for action. Fort St. Philip had 45. |

|

Convinced that any assault on New Orleans would come from the north, the Confederacy concentrated its defensive preparations at various points up the Mississippi. Recognizing that an attack could come from the south, an earthwork battery had been built directly across the river from Fort Jackson, connected to the larger fort by a chain barrier, through which a number of hulks (old ships, good for floating and being in the way and little else) were arranged to block anyone who was silly enough to attack from that unlikely direction.

In March of 1862, up from the Gulf of Mexico came the US Navy, represented by Captain David Farragut (1801-1870) at the head of six ships and twelve gunboats. Also present was a semi-autonomous group 26 "mortar schooners," an experimental naval concept (at least as far as Farragut was concerned) commanded by Farragut's foster brother, David Porter (1813-1891). Mortar ships, or bomb vessels, had actually been around since the end of the 17th century, first developed by the French...Perhaps Farragut's conviction that the mortar ships were a waste of time had more to do with their commander than their martial history.

|

| A gorgeous assessment of damage done to Fort Jackson during the Federal bombardment in April of 1862. Click on it, it's huge. |

|

After a great deal of fussy US Naval preparation that the Confederates were unable to hinder, Porter's mortar ships opened fire on April 18. The bombardment lasted for six days, and while the guns of Fort Jackson weren't silenced and only two of the fort's defenders were killed, seven guns were knocked out of action, most of the troops' quarters and the citadel were burned down, and everybody inside the fort was made really, really miserable.

One of the Federal vessels was sunk by return fire from the forts. Porter had boasted that his mortars would reduce both Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip within 48 hours, but on April 24 when the forts were still returning fire, Captain Farragut took matters into his own horny hands. |

|

At 3am on April 24th, Farragut's fleet started slipping through a gap in the chain that blocked the river bend. Once Fort Jackson's defenders spotted the threat they opened fire, as a column of the Federal ships returned it. Nobody hit much of anything, the combination of darkness, smoke and general confusion being just for what Farragut had hoped. Most of the Federal fleet made it past the forts with little if any damage: Only a couple of ships turned back when the sun started to come up, as it was assumed they would be easy targets in the light.

And where was the Confederate Navy during this mess, one might well ask? Hovering uncertainly just up the Mississippi for the most part. Confederate ships were indeed present, but when a few ventured down to engage the Federal ships as they were passing Fort Jackson, they were fired upon by Fort Jackson, whose gunners couldn't tell the sheep from the goats in the smoky darkness.

|

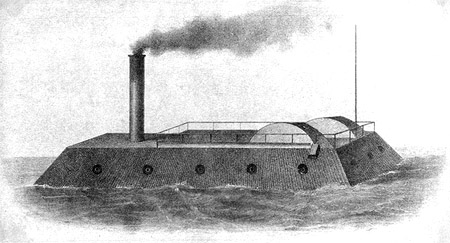

One notable Confederate naval presence was the CSS Louisiana, a brand-new ironclad of ten guns that was rushed down the river from New Orleans to head off the Federal scourge...more accurately it was towed downriver, with workmen still topside, hastily trying to complete attaching everything! The Louisiana was in place to trade shots with some of Farragut's ships, but to little effect.

|

|

CSS Louisiana CSS Louisiana |

|

The Confederate ships that met the Union fleet once it had gotten past Fort Jackson were disorganized. Unable to signal one another and act together, individual vessels tried to slug it out one-on-one, and were completely routed by Farragut's onslaught. The Federals lost one ship in the meleé, the Confederates twelve. Those commanding the Confederate ships that were left behind as Farragut raced up the Mississippi towards New Orleans knew that a large contingent of the United States Army was right behind the Federal fleet, which would be a-capturin' all before it, now that the Union Navy had so efficiently pulverized everything. The Louisiana and several other Confederate vessels were intentionally run aground and/or blown up by their crews, lest they be captured and turned against the south.

Some 8100 rounds had been fired at Fort Jackson and Fort St. Philip during the siege and battle, and the forts were a mess. The officers of Fort Jackson still intended to defend the fort from the oncoming US Army (which was under the command of General Benjamin Butler (1818-1893)), but the fort's garrison were having none of it. They mutinied and forced the officers to surrender the fort, which was really in no state to do anything of a defensive nature. Both forts officially surrendered to Union forces on April 28, 1862, who garrisoned Fort Jackson through the rest of the war. The fort was also used as a prison, which seems to be the fate of a great many starforts. Because who wouldn't want to be imprisoned in a starfort?!

|

| Battery Millar, built alongside Fort Jackson in 1898. Thank you, Secretary Endicott. |

|

When William Crowninshield Endicott (1826-1900), Secretary of War under US President Grover Cleveland (1837-1908), discovered through his study with the Endicott Board in 1886 that America's shores would be completely unable to defend itself from an attack by a modern navy, $127 million (eleventy bazillion dollars in today's money) was dedicated to violently beefing up US coastal defense. As part of this program, Fort Jackson was magically granted two modern gun batteries.

Battery Millar, mounting two 3" guns, was completed in 1898, and Battery Ransom, mounting two 8" disappearing guns, was completed in 1899. |

|

The aforementioned batteries were almost completed in time to defend New Orleans from the menacing, state-of-the-art Spanish armada that was stirred from its nest by the Spanish-American War (1898)! Actually, what Spanish fleet there was was too busy settling to the ocean floor off Havana and at the bottom of Manila Bay to do anything offensive in any direction. U! S! A!

Fort Jackson was manned during the First World War (1914-1918) as part of a coastal defense effort, but the troops left and its guns were removed by 1920. In 1927 the fort was declared "surplus," and sold to a private citizen of New Orleans, who donated it to Plaquemines Parish in 1962. Fort Jackson was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1960.

In the late 1960's, the political boss of Plaquemines Parish, Leander Perez (1891-1969), threatened to imprison any "hippies" or opponents of segregation at Fort Jackson, should they present themselves in "his" parish.

At the end of August of 2005, Hurricane Katrina did a variety of unpleasant things to New Orleans and its surrounding area. The combined destructive efforts of Katrina and Hurricane Rita the following month left Fort Jackson underwater for about six weeks, destroying a great many historical artifacts stored therein, and weakening the structure enough to keep it closed to the public to this day.

Closed and unsafe for operation or not, the needs of oily birdies in July of 2010 prompted Fort Jackson to be used as a cleaning station during the Deepwater Horizon oil spill...until someone remembered that there are always hurricanes coming this way, and the cleaning center was moved somewhere safer.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|