|

Fort Julien

Izbat Burj Rashid, Egypt

|

|

|

Constructed:

1470-1516, 1799-1802

Used by: Egypt, France,

Great Britain

Conflict in which it participated:

French Revolutionary Wars

Also known as: Fort Jullien, Citadel of Quaitbay

|

It is thanks to the French devotion to the starfort, and the Egyptian propensity for using their priceless artifacts as building materials, that we can understand hieroglyphs today.

By we, I mean we as in the world in general. I can't understand hieroglyphs. Don't be sending me hieroglyphic emails and expect me to understand them. |

|

|

|

The Nile is quite a river. Stretching 4,258 miles from Lake Victoria in central Africa to the Mediterranean Sea, it is the world's longest river...unless South America's Amazon is longer, which it either is or is not, depending on whom you ask. Bringing water to parts of the world that would otherwise be parched, the Nile also makes much fertile land for farming, particularly in the Nile River Delta, which is where Fort Julien hangs its metaphorical hat.

Folks have lived in the area of Izbat Burj Rashid since the days when sky god Horus ruled over Egypt (3000BC, plus or minus a thousand years), before deciding He could make more money and live a more relaxed life on the lecture circuit, plus making regular appearances at fan events such as San Diego Comic-Con, whereupon He resigned. At this time Menes became Egypt's first "human ruler."

|

Fort Julien With an Egyptian Boat, 1803. Fort Julien doesn't have much of a presence on the Internet. This is the only contemporary image that I could find, and it's more boat than fort. Since this was as the fort appeared in 1803, that flag you can't make out atop would be British. Or maybe Turkish. Note the three teepees to the fort's left, clear evidence of the presence of Lakota Indians! Fort Julien With an Egyptian Boat, 1803. Fort Julien doesn't have much of a presence on the Internet. This is the only contemporary image that I could find, and it's more boat than fort. Since this was as the fort appeared in 1803, that flag you can't make out atop would be British. Or maybe Turkish. Note the three teepees to the fort's left, clear evidence of the presence of Lakota Indians! |

|

In the 32nd century BC, a form of writing began to develop in Egypt, which would eventually include around 1,000 distinct elements. These were the fabled hieroglyphs, whose expressive characters sprawled entertainingly across all manner of ancient Egyptian items and structures.

This form of writing helped to fuel a mighty Egyptian dynasty that lasted thousands of years, but in the 4th century AD the Romans were in charge of Egypt, and all non-Christian temples were closed. Hieroglyphs were no longer in use, replaced by the effective but far less charming Roman alphabet...and their meaning slipped quietly into the mists of time.

And now, just maybe, it's time to start talking about a fort. |

|

By the mid-15th century the Ottoman Empire was expanding into Egypt, and the Egyptians were building forts to keep those wicked Turks out. Sultan Al-Ashraf Sayf ad-Din Qa'it Bay (1416-1496), known mercifully as Quaitbay, was the 18th Burji Mamluk Sultan of Egypt. He oversaw the construction of lots of stuff, but most notably for our present pursuit was responsible for fortification.

The Mamluks, who were until fairly recently known to western society as Mamelukes, were Muslim rulers and/or soldiers who began their careers as slaves. Young boys would be purchased from their families, trained as soldiers and eventually freed, whereupon they more or less willingly took their place in the ranks. 'Twas the Mamluks who fought the European crusaders in the 12th through 14th centuries in the Levant, ultimately ejecting those armored white guys from the region.

The original fort at Izbat Burj Rashid could be described as a "crusdader fort," high walls around a plain square with round towers as corner bastions, surrounding an interior blockhouse. It was initially known (and in some cases is still known) as the Citadel of Quaitbay, which is fine & dandy, except that Mr. Eponymous also built a much more famous Citadel of Quaitbay in Alexandria, only about 30 miles to the west. By all means o mighty Sultan, name your forts whatever you wish, but don't name them all the same thing.

|

Being built in 1470 would have put the creation of both Citadels of Quaitbay at the very moment that the starfort was being conceived in northern Italy, so Quaitbay can be excused his non-starry original design. While certainly nowhere near as secure against an attacker with artillery as would be a starfort, both Citadels' first versions made perfect sense when the expected opposition were swarthy little Turks with spears and arrows.

An outer wall was added to the fort in 1516, but the tide that was the Ottoman Empire wouldn't be stopped by such paltry measures, and Egypt fell to the Turk in 1517. Our fort was abandoned, and fell into a predictable state of disrepair.

The Ottoman Empire of the 17th century was vast, extending around much of the Mediterranean and Red Seas. As such it was difficult to defend everything to a sufficient degree, which made Egypt seem ripe for the plucking as far as Napoleon (1769-1821) was concerned.

|

|

The other, one might say the real, Citadel of Quaitbay in Alexandria, Egypt. The Citadel itself was built around the same time as what we now call Fort Julien, with its outer defenses being added in the early 19th century, shortly after the French left. The other, one might say the real, Citadel of Quaitbay in Alexandria, Egypt. The Citadel itself was built around the same time as what we now call Fort Julien, with its outer defenses being added in the early 19th century, shortly after the French left. |

|

France was ostensibly allied with the Ottoman Empire in 1798, but the opportunity to expand the French Empire by colonizing Egypt, while simultaneously denying British access to India was too great for Napoleon to resist. The future Corsican Tyrant landed with 30,000 French troops near Alexandria on July 1, 1798. Though miserably ill-supplied, the French made short work of the Mamluk and Bedouin forces that were so foolish as to meet them on the field (colorfully-dressed dudes swinging scimitars on horseback weren't ready for the European artillery-supported infantry square). Napoleon & co. dragged themselves 200 miles down the Nile to Cairo.

|

The interior of Fort Julien today. Not a whole lot of room for parading on a parade ground almost completely filled by a blockhouse! The interior of Fort Julien today. Not a whole lot of room for parading on a parade ground almost completely filled by a blockhouse! |

|

Early in this conflict, the French had taken possession of the Citadel of Quaitbay of Our Current Interest, whereupon they renamed it Fort Julien, after Thomas Prosper Jullien (1773-1798). Jullien, an aide-de-camp to Napoleon, was killed along with his escort in August of 1798, by the inhabitants of an Egyptian village called Alkham.

As the French will do, they recognized that the ramshackle little fort would be much more effective with pointed starfort bastions, at least on the landward side. A frantic construction effort ensued, which revealed that much of the stone that Quaitbay had used to build this fort came from old buildings in the area, and was frequently covered with hieroglyphics. |

|

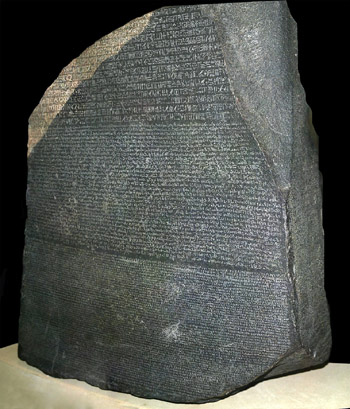

Lieutenant Pierre-François Bouchard (1771-1822), detailed to work on the upgrade of Fort Julien's defenses, made the most amazing discovery of all: Used as fill inside one of the fort's walls was the Rosetta Stone. Hieroglyphs had been a forgotten language for over a thousand years, but on this stone was a decree carved in 196BC for King Ptolemy V (210-181BC), in three languages...Hieroglyphics, demotic script and Ancient Greek.

Say what you will about Napoleon, but he was absolutely devoted to the advancement of science and education in general. With the French army to Egypt came a slew of historians, writers and scientists, all of whom had an interest in unlocking the secrets of ancient Egypt, which in the early 19th century was a black hole of history. The Rosetta Stone, with the same message carved in both unknown and known languages, made it possible for the first time to decipher the language of the ancient Egyptian pharaohs.

|

BUT...the Rosetta Stone today sits in London, not Paris. While Bouchard was able to convince Napoleon of the staggering significance of this discovery, the French were running out of time in Egypt. Before they had even found the Rosetta Stone, much less had a chance to transport the thing back to the mother country, the Royal Navy under the command of Sir Horatio Nelson (1758-1805) appeared in Aboukir Bay on August 1, 1798. Nelson defeated the French Navy there, trapping Napoleon in Egypt with no hope of support or resupply.

An Anglo-Turkish force of 2,000 men finally approached Fort Julien in March of 1801, with the intent of wresting it from the grasp of its 300-man French garrison. Gunboats and carronades (squatty shortish cannon with less range than properly-sized guns, but effective under the right circumstances) were dragged into position, and a two-day bombardment brought down Fort Julien's southwest bastion, which would be at the lower left in the image at the top of this page, on April 18, 1801. As the fort's garrison was thus exposed to Turkish sharpshooters, the French surrendered.

|

|

The Rosetta Stone, on display at the British Museum in London. The Rosetta Stone, on display at the British Museum in London. |

|

The French lost 41 men in the Siege of Fort Julien, to a British/Turkish three. One supposes that shouting "Stop shooting at us, you might damage the world-famous Rosetta Stone!" wouldn't have been a sound French tactic in this circumstance, as nobody had yet heard of the Rosetta Stone. Regardless, Napoleon eventually made it out of Egypt by way of Syria, but barely half of the troops with which he had arrived made it out with him.

|

|

|

After some wrangling and negotiating with the French scholars who claimed the Rosetta Stone and the many other historical Egyptian treasures they had found, the stone was brought back to England and laid at the feet of King George III (1738-1820). The King decreed that the stone would be displayed in the British Museum, where it still sits today. In 1820, French scholar Jean-François Champollion (1790-1832) began the lengthy process of deciphering the Rosetta Stone, which ultimately unlocked its secrets. A worldwide Egyptology craze ensued, which led to lots of bad western architecture that attempted to reproduce the building style of ancient Egypt. This included, weirdly, the main gate of Fort Trumbull in New London, Connecticut ( Click here to see). |

|

Fort Julien was restored in the 1980's, and officially reopened in 1985 by Egyptian president Hosni Mubarak (1928- ). Today it is open to the public, which no doubt scratches at the walls, hoping to unearth yet another priceless treasure.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|