|

Kuressaare Castle

Saaremaa, Estonia

|

|

|

Constructed: 1600-1640,

1684-1706

Used by: The Livonian Order, Denmark, Sweden, Russia

Conflict in which it participated:

Great Northern War

|

In 1227, Saaremaa was the last county in Estonia to surrender to the rampaging German crusaders. Saaremaa is an island off of Estona, which made it a far-flung territory for the Teutonic knights to dominate. Uprisings were common, and by the 1260's the Livonian Order, a branch of German knights, started building a castle-like fortification for their Bishop to hide in when the Saaremaanians were feeling frisky.

|

|

|

|

Various improvements were made to the castle and its walls over the next few centuries, but it wasn't until the 17th century that Kuressaare Castle took on the spectacularly starrish shape we see today. Kuressaare Castle resident Bishop Johannes V von Münchhausen sold his lands to the Danes in 1559, not wishing to be present when the Russians showed up as expected in the ongoing Livonian War (1558-1583).

|

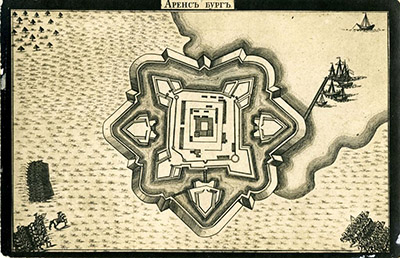

An image of Kuressaare Castle from 1713 (likely representing the Russian approach to the fort during the Great Northern War), which appears to feature troops of cavalry cantering purposefully atop the Baltic Sea and mighty ships sitting on the landmass of Saaremaa, until one realizes that this image shows the fort upside-down. Which is totally cool, as the concept of "north" and "south" are relative. An image of Kuressaare Castle from 1713 (likely representing the Russian approach to the fort during the Great Northern War), which appears to feature troops of cavalry cantering purposefully atop the Baltic Sea and mighty ships sitting on the landmass of Saaremaa, until one realizes that this image shows the fort upside-down. Which is totally cool, as the concept of "north" and "south" are relative. |

|

The Castle's new Danish owners stared at its puny walls and stroked their chins in contemplation for four decades (fortunately the Russians did not march on Saaremaa during this contemplative period), and then finally got to work surrounding the castle with a proper starfort around 1600. The end result, completed in 1640, was a classic, four-bastioned starfort surrounded by a seawater moat which was up to 30 meters wide.

A mere five years after having completed their newest starfort, the Danes were forced to hand it over to Sweden. The Tortensen War (1643-1645) was just one of many bloody squabbles betwixt the Danes and Swedes to take place in the 17th century, and it ended with Denmark ceding a number of its landholdings to Sweden. |

|

One of these lands was the island of Øsel, which is what the Danes called Saaremaa. Kuressaare Castle's new owners began a modernization process in 1684, which eventually resulted in the three ravelins we see today, which were intended to protect the starfort's curtain walls from direct fire. A fourth, seaward ravelin was planned, but work on the Castle ceased in 1706 before it could be built.

|

All of Sweden's dandy new additions to Kuressaare Castle were for naught, however. The Great Northern War (1700-1721), fought primarily betwixt Russia and Sweden, brought Russian troops to the castle of our current interest on September 15, 1710. The Swedish garrison, weakened by the plague, immediately surrendered... and what could be more appealing to an attacking army than a fort filled with plague-consumed corpses?

Unpleasant or not, the Russians spent that winter at Kuressaare Castle.

|

|

|

|

Upon their departure from Kuressaare Castle in the Spring of 1711, the Russians destroyed much of the fort. The conclusion of the Great Northern War brought with it much land-swapping, during which all of modern Estonia was ceded to Russia.

|

Kuressaare Castle's northernmost bastion, in thoughtful repose Kuressaare Castle's northernmost bastion, in thoughtful repose |

|

In 1762 Russia began a series of repairs and upgrades to the Castle, but by the beginning of the 19th century the endless struggle against the wicked Swedes had moved elsewhere, leaving Kuressaare far from the action. In 1835 Tsar Nicholas I (1796-1855) sold Kuressaare Castle to the Knighthood of Saaremaa (whomever they were) for 3,000 rubles, and the following year the fort was officially "excluded from the list of fortifications," meaning it was no longer considered to be of any military value.

As we have frequently seen, however, a starfort is a useful structure, and rarely left to wither on the vine in modern times. Beginning in the 1860's, Kuressaare Castle's buildings were used for a variety of peaceable purposes. |

|

A dedicated restoration effort began in 1968. The second phase of this effort, which intends to represent the development of the fort's defenses from the 14th through 18th centuries, continues to this day. Today Kuressaare Castle is home to the Saaramaa Museum.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|