|

Forteresse Île du Large

Îles Saint-Marcouf, Normandy, France

|

|

|

Constructed: 1803-1812, 1860-1867

Used by: France, United States

Conflict in which it participated:

Second World War

Also known as: Forteresse St. Marcouf

|

Four miles east of the Cotentin peninsula in Normandy sit the Îles Saint-Marcouf. Consisting of Île de Terre and the larger (surprise!) Île du Large, the islands take their collective name from Saint Marcouf (500-558AD), who was reportedly able to cure scrofula (a particularly gross form of tuberculosis that was common in immunocompromised folks, such as notoriously inbred European royalty) with the laying on of hands. |

|

|

|

The islands were named for Saint Marcouf because he died there! As was the case with many European islands that were close to the mainland, the Îles Saint-Marcouf were populated by Monks, on and off into the 15th century.

Thanks to the determined growth of the English Navy, the English Channel (to which the French refer as La Manche) was for the most part much an English waterway...and the French islands therein were either taken by the British, or were under constant threat therefrom. It is unsurprising, then, that the British occupied the Îles Saint-Marcouf in 1795.

|

The Îles Saint-Marcouf: Íle du Large in the foreground, and wee little Île de Terre. The Îles Saint-Marcouf: Íle du Large in the foreground, and wee little Île de Terre. |

|

The French Revolution was a most unsettling event for all of Europe. For centuries France had been, if not precisely a fantastic neighbor, at least a relatively stable entity...but once France's masses committed to throw off the shackles of their monarchy, Europe was thrown into a tailspin from which it took 25 years and many thousands of lives to recover.

One thing Great Britain could be depended upon to do was get involved in European affairs. The Royal Navy occupied the Îles Saint-Marcouf in July of 1795, built barracks, redoubts and shore batteries, and used the post as a forward base for the blockade of the French naval ports along the Cotentin coast. |

|

Historically unwilling to try to pronounce French words if they could help it, the British named the Îles East and West Islands: East was the larger of the two, but they concentrated most of their efforts on West, as it was closer to the French mainland. Seventeen guns armed West Island's batteries, including two 32-pounder carronades...East Island's battery only boasted two carronades, but they were 68-pounder monsters. A number of British ships were assigned to the islands' protection, including the HMS Sandfly, a "floating battery" that was designed specifically for this mission.

One of France's dearest wishes (and later a dear wish of Germany) was that they would be able to cross the Channel, invade England and rid itself of that most meddlesome foe...or at the very least, give England something to think about other than participating in things that didn't concern it on the continent. Amphibious landings weren't endeavors in which militaries regularly indulged during this period, however, so the French were beavering away on new technologies that would make it possible.

|

The French, predictably, wanted their Îles back, and what better opportunity to test their new amphibious landing craft (which seem to have amounted to whaleboats with huge, unwieldy cannon in them) than in an "invasion rehearsal?" After waiting for the right weather and sea conditions to prevent the Royal Navy from being able to interfere, a force of 5,000 to 6,000 French troops in 52 boats paddled their way to East Island in the dawn of May 7, 1798.

If you would be so kind as to look slightly to the right, you will see the result of the French attack. West Island's gun batteries and, as the French got within 50 yards of shore, Royal Marine musket fire wreaked havoc on the invasion force.

|

|

A British depiction of the attack of May 7, 1798. All those desperately flailing French arms! A British depiction of the attack of May 7, 1798. All those desperately flailing French arms! |

|

Having determined that the attack was a failure, the retreating French somehow strayed too close to West Island, whose carronades exacted an even higher toll on the would-be attackers. In all, the French lost around 900 men killed or drowned, and suffered an additional 300 wounded: Of their 500-man force, the British lost one Marine killed, and four others wounded. This shambles of an invasion rehearsal did wonders for the morale of the British, who were naturally concerned about invasion...and caused the French to reconsider future cross-Channel forays.

Another attempt to take the islands from the British was ordered, but never came about. With the Royal Navy constantly prowling thereabouts, a shipborne invasion wasn't possible. But what if those British vessels could be snuffed out, one by one, from beneath the waves?

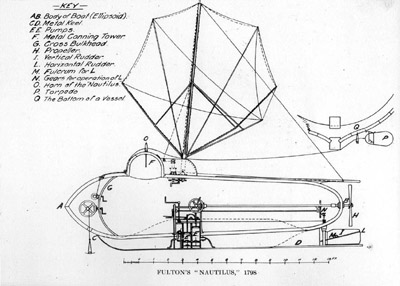

All American schoolchildren (at least from my generation) are (were) taught that Robert Fulton (1765-1815) "invented" the steamboat in 1807, which played a major role in the commercial development of the United States. Prior to this inventive feat, however, Fulton was in the employ of Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821), who by 1800 was First Consul of the French Republic.

|

Robert Fulton's Nautilus, developed in the 1790's: One of several "First practical submarines." Robert Fulton's Nautilus, developed in the 1790's: One of several "First practical submarines." |

|

Fulton insisted that he could tip the naval balance in France's favor with a craft that could motivate beneath the waves, invisible to surface ships, to which an explosive "carcass" could be affixed...whereupon we could all disparagingly discharge the contents of our noses in the general direction of the British Admiralty, because the Royal Navy would cease to be a threat to France.

Fulton's masterpiece, the Nautilus, was a 21-foot-long submersible that was powered by two guys inside turning a crank attached to a propeller. The Îles Saint-Marcouf almost became part of naval history when on September 12, 1800, the Nautilus set its sights on the British gunboats protecting the islands. |

|

Unfortunately for naval history, the Nautilus was a bit on the unwieldy side, and the targeted British ships moved before the submarine could get to them. No way you could have predicted that, eh Fulton? Two such attempts failed because of the Royal Navy's perverse habit of making their ships move, and winter weather prevented any further submarinal sallies. The Nautilus is remembered as the world's first practical submarine: The Confederate Hunley, utilized during the American Civil War (1861-1865) is another "first practical submarine." I would propose that a military submarine would need to be able to both accomplish its mission and not kill its own crew to be "practical." But I'm a fake starfort expert, not a fake submarine expert.

Disgusted with this expensive failure, Napoleon dismissed Fulton, who wound up in Great Britain. The British Admiralty felt that the submarine concept showed promise, and contracted the American to develop his wonder-weapon for them. The Battle of Trafalgar (October 21, 1805) betwixt the Royal Navy and the combined French and Spanish Navies resulted in such a decisive victory for the British, however, that they no longer felt France's naval power to be of concern. The Admiralty then ignored Fulton until he got frustrated, went home, and invented the steamboat.

|

All of the violent brouhaha over the Îles Saint-Marcouf notwithstanding, they were lost to the British with the stroke of a pen, thanks to 1802's Treaty of Amiens. With this treaty peace was (briefly) restored, Great Britain recognized the French Republic, and several islands and colonial possessions were traded back 'n' forth. British troops left the île in May of 1802, and the French, having been shown precisely how defensible this island was, began work on a proper fortification on Île du Large in 1803.

The coliseumesque, circular fort we see to the right, completed in 1812, was the fruit of this French labor.

|

|

The first part of the Forteresse Île du Large, completed in 1812. The first part of the Forteresse Île du Large, completed in 1812. |

|

The French were of course masters of the starfort, but this stout, circular design certainly made sense on a small island without much room for fancy bastions. It was 53 feet in diameter, with two levels of 24 casemates each: Each casemate had a firing port, making for...wait, let me do the tricky math here...48 firing embrasures in all. The Forteresse had seven underground chambers and a cistern, and was intended to accommodate a garrison of 500 men.

Disappointingly, the British never tried to take the île back...maybe because they couldn't find it, reasoned the French, who installed a lighthouse on the island in 1840: Still no British attack. Fortifications were built on the Île de Terre from 1849 to 1858, consisting of a shore battery and a guard house with room for 60 men.

Those who had fond memories of the days when France bombastically pushed its weight around on the European stage were surely pleased when Napoleon III (1808-1873) declared himself Emperor in 1852. Though this Napoleon allied France with England for the Crimean War (1853-1856) and ultimately spent his last days peacefully exiled in Great Britain, he also undertook a great deal of aggressive war preparation, and frequently harrumphed in a threatening fashion towards Great Britain: The British Palmerston Forts were built in the 1860's in reaction to the renewed French threat.

|

The Forteresse's moat, cleaved from the Île du Large's rock in the 1860's. The Forteresse's moat, cleaved from the Île du Large's rock in the 1860's. |

|

Accordingly, the fort on Île du Large was strengthened from 1860 to 1867: Some slightly starfortish, bastionlike works were added, and the whole was surrounded by a moat that was chipped from the island's rock. A powder magazine, semaphore station and quay also joined the festivities. Île de Terre's fortifications were enhanced by adding a moat around the guardhouse, making it an instant blockhouse.

Napoleon III met his match in Iron Chancellor Otto von Bismarck (1815-1898), when the latter maneuvered the former into war before the former was ready for it. |

|

Captured at Sedan during the Franco-Prusian War (1870-1871), Napoleon III wound up exiled in England, where surely he fumed over the fact that nobody ever attacked the Île du Large after he had so lavishly upgraded its fortifications. September of 1870 brought Prussian troops into France, who occupied the ring of fortifications the French had built to defend Paris from the exact sort of thing that was presently happening. Many folks in Paris felt resentment toward their silly government while under siege, which discontent became rebellion. The Paris Commune served as Paris' government from March until May of 1871, when French troops stormed the city, killed around 18,000 persons and jailed another 25,000. 200 of these Communards, as they were known, spent some time imprisoned on Île du Large in 1871, under "deplorable conditions." The world passed our Forteresse by for the next several decades, until Germany landed on the undefended Îles Saint-Marcouf in 1940: The Second World War (1939-1945) saw Germany taking possession of, and utilizing, many a European starfort, in many cases "enhancing" them with ugly concrete bunkers and such. Apparently the Nazis felt that the Forteresse Île du Large was absolutely perfect just the way it was, because they made no enhancements... other than to remove its 1840 lighthouse, and seed the island with mines before leaving in 1944.

|

June 6 of 1944 brought the combined American, British and Canadian invasion of Fortress Europe: D-Day, which took place in exactly the neck of the woods that we've been discussing!

The Îles Saint-Marcouf became the first French territory liberated by the Allies on this day, when four US soldiers swam ashore, armed only with knives, to scout out the opposition. Finding the islands abandoned, 132 troops from the US 4th Cavalry Group came ashore...and suffered 19 casualties from the mines left behind by the departing Germans. Land mines: For when you want to show you care, but don't wish to stick around to say it in person.

|

|

Île de Terre, with the remains of its moated blockhouse and what one imagines is what's left of its battery right next to it. Île de Terre, with the remains of its moated blockhouse and what one imagines is what's left of its battery right next to it. |

|

Île de Terre was designated a nature preserve in 1967, but Île du Large was off-limits to visitors for safety concerns until the 21st century. The Friends of Saint-Marcouf organization was established in 2003, and lobbied the government for the chance to undertake preservation work on the fort, with the end goal of making it safe and accessible to the public. Tourism in Normandy is big business, and the îles' proximity to Utah Beach, one of the D-Day invasion's main landing areas, make them a desirable tourist spot...as long as the walls don't crumble under a visitor's feet! If you're interested in supporting the Friends of Saint-Marcouf's efforts, you can make a donation at their website. Many thanks to determined starfort-discoverer Nico Pfeifler, who alerted us to the Forteresse Île du Large!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|