|

Fort Mackinac

Mackinac Island, Michigan, USA

|

|

|

Initiated: 1780

Used by: Great Britain, United States

Conflict in which it participated:

War of 1812

Allegedly pronounced: Mackinaw*

|

The border between the United States and Canada is the world's "longest international border" (meaning longest betwixt two individual nations): 8891 miles, which of course includes the border with Alaska. Even prior to Alaska being part of this calculation, that oft-disputed US/Canadian border was nearly 7400 miles long. How would a nation even attempt to defend such an expanse, back in the days of starfortery? |

|

|

|

Fortunately, no nation had to. From the time of the American Revolution up to the 1860's Canada was essentially Great Britain, with whom the United States most assuredly did not get along; but nobody really cared about the defense of that entire length of border, because west of the Great Lakes was mostly nothing, aside from countless moose, Indians, trees and beaver...few of whom/which would have cared one way or another about a starfort. The 1600-odd-mile border that stretched from the Atlantic Ocean west to the tip of Lake Superior's pointy nose was the only section that was ever fortified in any meaningful way, and most of those efforts were clustered around a small number of chokepoints. One of those points was the spot where two of the Great Lakes, namely Huron and Michigan, join: The Straits of Mackinac.

|

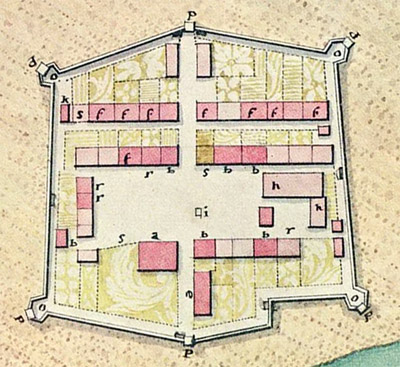

Fort Michilimackinac, drawn by Lt. Perkins Magra of the British 17th Regiment in 1765. Click it to see the whole map (and learn what all those s's and f's are), and thanks to Mackinacparks.com for the image! Fort Michilimackinac, drawn by Lt. Perkins Magra of the British 17th Regiment in 1765. Click it to see the whole map (and learn what all those s's and f's are), and thanks to Mackinacparks.com for the image! |

|

French Explorer Jean Nicolet (1598ish-1642) was the first European to investigate the area, around 1634. French missionaries noted with dismayed alarm that the local Ojibwe Indians weren't Christians, and therefore established a mission on little Mackinac Island in 1670.

The Ojibwe were of course responsible for all of the entertaining names in this region: They felt that what is now known as Mackinac Island looked like a big turtle, so they named it Michilimackinac, which means, unsurprisingly, big turtle.

Michilimackinac was the name by which the entire immediate region was known, until the British came along and did what the British always did, which was make things easier for themselves to pronounce. Before the British got a chance to undertake their ritual renaming, however, the French built Fort Michilimackinac on the mainland southwest of Mackinac Island.

|

|

|

The French constructed what they should have named Fort Grosse Tortue (Fort Big Turtle in French, Fort Michilimackinac in Ojibwe and English, in this specific instance) around 1715, on the southern banks of the strait, at what is today Mackinaw City, Michigan: This was a stockade fort, anchored by six blockhouses. In addition to attempting to benefit the eternal souls of the locals, the French were of course also interested in making money, and fur was money at that time and place: Fort Michilimackinac was one of a series of fortified trading posts that spanned from the Atlantic Ocean through the Great Lakes, and down the Mississippi River.

The Seven years' War (1756-1763) concluded with one of the many, many treaties known as the Treaty of Paris (Wikipedia lists around 40 of them), in which France agreed to surrender virtually all of its colonies in the western hemisphere to Great Britain. This included Fort Michilimackinac and its environs, which eventually presented a problem for the locals. The French version of the Great White Father had instituted a policy of annually giving gifts to the local Indians, which may or may not have been financially supportable in the long term, but at least kept the Ojibwe content enough that they weren't disrupting French commercial activity. Given the British reputation for managing their interactions with North American native peoples less successfully than did the French, it is unsurprising that, once in charge of the Michilimackinac region, the Brits declined to continue the giftgiving tradition.

|

Already displeased at being left out of the peace process betwixt France and England, the Ojibwe found their new giftless situation to be intolerable. Other Indian tribes in the Great Lakes region were equally unhappy with British rule, so Odawa leader Pontiac (1714/20-1769) decided to name a war after himself.

Pontiac's War (1763-1766) launched in May of 1763 with several British forts being attacked, but the garrison at Fort Michilimackinac was tragically complacent. On June 4, 1763, a group of Ojibwe initiated a hearty game of baaga'adowe (lacrosse) near the fort's main gate. That gate was opened so the fort's inhabitants could watch the game, and sure enough, 'twas but a clever ruse to gain entrance! Was this the only time in history that such a sports-based gambit was successfully enacted in the interest of semistarfort appropriation? Surely not, and we'll be on the lookout for more instances!

The insidious lacrosse players killed 16 of the 35 British troops stationed at Fort Michilimackinac, and captured the rest: An additional 54 British settlers were killed in the attack. The fort was held by French Canadians for about a year, until the British returned and recaptured it. |

|

I've always thought lacrosse was too violent of a sport. Thanks to Drhartnell.com for the image! I've always thought lacrosse was too violent of a sport. Thanks to Drhartnell.com for the image! |

|

Having learned their lesson, the British promised the Indians newer and better annual gifts, and everybody was happy...but once the American Revolution (1775-1783) got underway, British authorities made the wise decision to relocate Fort Michilimackinac, concluding that the original location was clearly too vulnerable to organized sporting events. What tragedy would befall the fort if the Americans showed up and started playing baseball nearby? Unthinkable.

Big Turtle (Michilimackinac) Island, about five miles northeast of Fort Michilimackinac's initial location, was chosen as the easily-defensible new fort site. Under the auspices of Major Patrick Sinclair (1736-1820), Lieutenant Governor and Superintendant of Michilimackinac, work on the new and improved fort was begun in 1780 and completed in 1781. This was to be a more formidable affair than the wooden fort it replaced, in that much of the new Fort Mackinac was built of limestone. Sadly, this awesome fortification went unchallenged during the American Revolution.

|

One of Fort Mackinac's two blockhouses, as depicted by the Detroit Publishing Co., dated 1890-1901. Thank you, Library of Congress! One of Fort Mackinac's two blockhouses, as depicted by the Detroit Publishing Co., dated 1890-1901. Thank you, Library of Congress! |

|

The latest Treaty of Paris (1783) officially ended the war in the favor of the newly-minted United States of America. One of the treaty's stipulations was that the British were to relinquish their control of forts in United States territory with all convenient speed, but the terms "convenient" and "speed" meant different things to different parties.

Great Britain retained two forts at the mouth of Lake Champlain and five forts in the Great Lakes region, one of which was, you guessed it, Fort Mackinac. Great Britain claimed that this was due to the dangerously unsettled regional situation, and/or in retaliation for the Americans reneging on other parts of the treaty...but one suspects that the British never intended to give up these forts.

|

|

|

But give them up the British did, thanks to the Jay Treaty (1794)! Should you be so inclined, you may read all about the starforts that were affected by the Jay Treaty on our Jay Treaty page. The men in red departed, and Fort Mackinac was finally occupied by American troops on September 1, 1796.

|

When the United States declared war on Great Britain in June of 1812, sixty men under the command of a Lieutenant Porter Hanks garrisoned Fort Mackinac. Thanks to the alacrity of the British commander in the region, Major-General Sir Isaac Brock (1769-1812), the British learned that a state of war existed before the Americans did. Note to war-declaring nations: Make sure to get the word out to your starforts before the enemy gets to 'em! (Brock is starfort Royalty, in that upon his death at the Battle of Queenston Heights in October of 1813, he was buried in the northwestern-facing bastion of Fort George, which heroically contests Fort Niagara across the Niagara River, where it meets Lake Ontario.)

|

|

Fort Mackinac as it appeared from Mackinac Island's wee harbor, in 1899. Thanks again, loc.gov! |

|

On the morning of July 17, 1812, a force of 200 British and Canadian troops, along with an indeterminate number ("a few hundred") of Native Americans from various tribes landed on Mackinac Island. Lieutenant Hanks and his men were taken by surprise, being unaware that they were at war, and surrendered Fort Mackinac to the British without a fight. They were vastly outnumbered, and when them wild Injuns were involved in warfare and allied with Eurpean armies, an effective threat was always, "...if you don't surrender, I can't guarantee that these ungovernable Indians won't kill all of you very slowly, in a most unpleasant fashion..." Hanks and his men were permitted to depart unmolested, but when he returned to Detroit he was charged with cowardice for surrendering Fort Mackinac. Fortunately Hanks' career wasn't blighted by a court martial, as before it had a chance to convene he was cut in half by a British cannonball when the British attacked Fort Lernoult in August of 1812.

|

The diminutive horseshoefort that is Fort Holmes. The diminutive horseshoefort that is Fort Holmes. |

|

Fort George/Fort HolmesThe Brits 'n' their peeps easily captured Fort Mackinac not only because they had surprise and numbers on their side, but also because they had landed on the opposite side of Mackinac Island from the fort, marched unopposed overland and appeared as if by Britannic magic at Fort Mackinac's back door. In order to prevent the same thing from happening to them, the British built Fort George (there were almost as many Fort Georges as there were Treaties of Paris) on the highest point of the island, shortly after capturing Fort Mackinac.

Fort George wasn't much, but it didn't have to be much to succeed in its mission. Essentially just a blockhouse surrounded by horseshoe-shaped earthworks, it was (and still is) connected to Fort Mackinac by a 600-yard-long covered way. Petite though it may have been, Fort George proved its worth in August of 1814.

On July 26, Five American warships disgorged 700 troops at the same spot of Mackinack Island where the British had landed two years earlier. As the sneaky overland approach had worked in 1812, it was reasoned that it would also work in 1814. |

|

|

The unwelcome surprise of Fort George was soon discovered by the American attackers, and the US Navy was asked to reduce it to rubble, so that the silent lightning raid on Fort Mackinac might continue. At 320 feet above lake level, however, Fort George proved to be too high for the naval guns to meaningfully bombard: Most of the rounds landed semi-harmlessly in vegetable gardens around the fort ("There go my bloody leeks," muttered Sergeant Erstwhile). A heavy fog then blew in, making further offensive operations impossible, and the Americans were forced to wait it out in their comfy ships: I believe it would be safe to say that the element of surprise had been lost by this point.

|

When the Americans returned, they were led by Major Andrew Holmes (1782-1814). The British had not been idle in the fog, and built a breastwork to cover a clearing below Fort George, armed with two field pieces and a "small number" of musketeers. This clearing was exactly where Holmes led his men on August 14: 13 Americans were killed (including Holmes and two other officers), with another 51 wounded. Stunned by this turnaround, the Americans scampered back to their ships and departed.

This shambolic episode is known as the Battle of Mackinac Island, and while it's difficult to classify it as a battle, calling it Ambush Near Fort George That the Americans Walked Right Into is much less impressive-sounding for either side.

|

|

Fort Holmes around 1890. Sensible place for a radio tower! Once again, this image comes to us courtesy of LOC.gov. |

|

Due to his quick thinking on Mackinac Island, Major Holmes had a county named after him in Ohio, a city in Mississippi and as American fotified works are usually named for the heroically dead, Fort George was renamed Fort Holmes once Mackinac Island was returned to American control upon the conclusion of the War of 1812 (1812-1815).

As important a border fortification as Fort Mackinac was for so many years, it was hard for the US Army to give up on it, despite the gradual lessening of tension between the US and Canada. Our fort remained manned and technically active into the 1870's, but whenever there was an actual war to fight, Fort Mackinac's garrison rushed off to join the party while it was left under the supervision of a single ordnance sergeant.

During the US Civil War (1861-1865) three Confederate "political" prisoners were held at Fort Mackinac. It was desired that these prisoners sign oaths of loyalty to the federal government before being released, but when they were first delivered to Fort Mackinac in the summertime and given freedom to romp about on the island, they wondered what kind of hardship this "prison" was supposed to be? Then, winter came. Two of the prisoners willingly singed their loyalty oaths and were permitted to depart for warmer climes, and when the third continued to resist loyalty, he was moved to another facility...along with his jailers, who didn't want to spend the winter on Mackinac Island either.

|

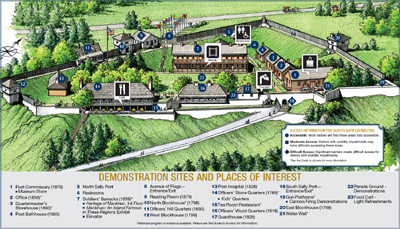

The current map of the main attration of Fort Mackinac State Park. |

|

By 1875, it was clear to even the most rabid anti-Canada zealots that there would be no further episodes of wanton Canadian warmongery against the United States, and Fort Mackinac became the second National Park, after Yellowstone. Troops were moved back to the fort to both maintain it and act as park rangers.

In 1895 the federal government presented Fort Mackinac to the state of Michigan, which graciously accepted and made it their first State Park, which is what it is today. |

|

|

Fort Mackinac State Park is open from May through October each year, global pandemic permitting. Reenactors dressed as US troops circa 1887 man the fort, sporting the oft-overlooked-if-not-openly-mocked pickelhaube, the spiked headgear that was all the rage amongst western militaries at the end of the 19th century: Thanks, Prussia.

*A thought on the pronunciation of Mackinac: According to several sources, "Mackinac" is properly pronounced "Mackinaw." You will note that the city at the tippy tip of Michigan, just southwest of Mackinac Island, went whole hog and is even spelled Mackinaw. Now, localities may pronounce their locations however they see fit of course, but if the word whence comes all of the derivitaves is the original Ojibwe Michilimackinac, which word was notionally phonetically spelled based on the original pronunciation, why was that word not Michilimackinaw? Could it be because it was the French who did the initial European spelling, and we know that they're physically incapable of pronouncing consonants at the ends of words? My Ohio-native father visited Fort Mackinac as a small person at or around 1955, and remembers that they all pronounced it with the ending "ack," but they were just going by what the signs said. If somebody out there knows the answer to this quandry, I sure would appreciate an email.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|