|

Perekop Fortress

Perekop, Crimea

|

|

|

Constructed: 1509ish

Also known as: Or-Kapu

Used by: Crimean Tartars,

Ottoman Empire, Russia, Germany

Conflicts in which it participated:

Russian-Turkish Wars,

Russian Civil War, Second World War

|

Crimea is a peninsula that sticks out into the Black Sea. Its border with what is today the Ukraine is about fifty miles long, but almost all of that border consisits of the Syvash Lagoon System. A whopping five miles of solid ground is the only means by wish one might walk into the Crimea: The Isthmus of Perekop. |

|

|

|

Who was responsible for the first ditch stretching across this isthmus is a bit of an open question, but it may have been the Romans, who had some measure of control in the region in the first century BC, and who were responsible for lots of first fortificational efforts in and around Europe. The story of the starfort of our current interest, however, really begins with the Crimean Khanate, which came into being in the mid-15th century.

The Great Horde of Desht-i Kipchak, a bloodthirsty nomadic tribe that galloped about Asia in a menacing fashion in and/or around the 14th century, decided that it needed to settle down and repent from its nomadic ways. The Horde determined that the Crimea would be its new yurt, or homeland. Crimea was at that time under the control of a different Horde, the Golden Horde of the Mongol Empire. Decades of interHorde warfare followed, and by the mid-15th century the Great Horde, having victoriously yurtified the Crimea, gentrified itself with the new name of the Crimean Khanate. The Ottoman Empire would shortly weasel its way into the Crimea, and the Crimean Khanate became a vassal state of the Ottomans.

|

The entire width of the Isthmus of Perekop: There's our fortress near the center to the right! The village of Perekop is just to its north, and the North Crimean Canal slashes in a most unsightly fashion through, left of center. The entire width of the Isthmus of Perekop: There's our fortress near the center to the right! The village of Perekop is just to its north, and the North Crimean Canal slashes in a most unsightly fashion through, left of center. |

|

Just to the north of Crimea, however, were the Kievian Rus. Though by the start of the 16th century the Rus were past their days as the most powerful state in central Europe and were in a period of foreign domination, the Crimean Khanate certainly didn't want those Kievians stomping all over their yurt, and thus fortified their northern border by expanding on the ancient moat that may or may not have been initiated by the Romans of long ago.

The Khanate upgraded their border fortification over the next couple of centuries, adding a variety of strongpoints...but none were as strong as the Golden Gate. |

|

|

But it would be a while before the muddy ditch-fort of our current interest could reasonably be called the Golden Gate. The moat was known as Perekopskiy Val, or Perekop Shaft, and the fort was called Or-Kapu by its creators, the Crimean Tartars (Or means "ditch" in their language). Shaft and attendant forts did their job of keeping the border reasonably secure for nearly 300 years...but during that period the Kievian Rus had morphed into the Russian Empire, whose globe-spanning power was eclipsed only by that of the British. As Russia expanded, it naturally came into (frequent) conflict with the Ottoman Empire, and the two empires entertained each other with several wars...at least a dozen between 1568 and 1918 by my count, which seems like a lot, but then all of Europe was pretty much constantly fighting amongst itself during this period.

The Ottoman version of Perekop Fortress was a five-bastioned, rectangular design, with earthen walls lined with stone. The first version was completed around 1509, but the fort was of course built and rebuilt over many decades, utilizing the skills of various Italian and Dutch starfort engineers. It sported twenty, four-sided towers (each covered with ruby-red tiles) with an armory, wheat barns, and several wells inside, and mounted around 100 guns. The fort was manned not only by Crimean Tartars but Turkish troops.

|

In some inexplicable fashion, from the 17th century on, Perekop was the name of a fort, a city and a village, all around the same place. This trifecta of regional confusion was beseiged on three occasions by Russia: Unsuccessfully in 1689 ("Crapski, it's a fort, a city and a village?! Why didn't you tell us that before we started besieging?!"), but successfully in 1736 and 1771, which finally left our fort, for a time, in ruins.

Russian interest in the Perekop Isthmus up to this point hadn't been so much about conquest of the Crimea as access to it, which is why they tended to bash Perekopskiy Val's fortifications, move a bit inland and hang out for a while, but then scuttle away, chortling indulgently. This ambivilent attitude ceased, however, with the advent of Catherine the Great (1729-1796).

|

|

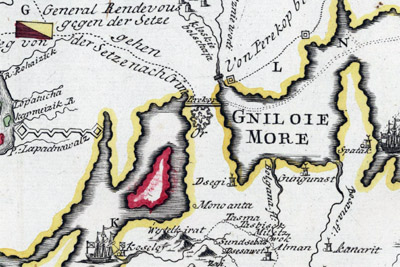

From the map Operationen am Donn und Dnieper 1736, a German interpretation of 1736's events of the Russian-Turkish War. There's Perekop Fortress represented with a generic illustration of a multipointed flower-thing, right between Das Schwartze Meer and the Gniloie More. Click it to see the whole map, which is huge, and shows a bunch of starforts sprinkled through the countryside. Maybe the remains of some of those forts are still around, but I looked for a while and couldn't find 'em. |

|

Upon its defeat in the Russo-Turkish War of 1768-74, Turkey signed the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca, which made the Crimean Khanate independent from the Ottoman Empire, but dependant on Russia. Russian troops garrisoned Crimean forts at Yeni-Kale and Kerch, and Russian settlement became widespread. Finally, Catherine went ahead and made a Proclamation of Annexation on April 19, 1783.

|

The Storm of Perekop, 1771: a painting from 1791, on the 20th anniversary of the battle. Forgive me for being unsure, but which way is north? Since Perekop Fortress lies slightly to the west of center of the isthmus, I guess we're looking down from the Russian side of the border? So north is down, and south is up. |

|

Perekop's new owners planned an extensive overhaul of shaft and fortress, but somebody must have pointed out that a strong border defense wasn't really necessary any more, because north and south of this ditch was now all Russia, and little work was completed.

The Russian garrsion pulled out before too long, and Perekop Fortress was only used for "quarantine measures." 1835 saw the state handing responsibility for shaft and fortress over to the city authorities of Perekop, which were probably overjoyed with the opportunity to maintain such a huge and seemingly useless edifice.

Things continued to worsen for our fortress through the rest of the 19th century, as it was abandoned, a state which folks who live nearby historically take as permission to cart off whatever's not nailed down as building materials.

|

|

|

When the Russian Revolution broke out in 1917, a great many people, across a vast expanse of the globe, had absolutely no idea what was going on. This included the folks in the Crimea, which changed hands betwixt the Bolsheviks and Whites on numerous occasions. By 1920 it had become a stronghold of the Whites, who were desperately fighting to restore Russia's doomed monarchy. Though Perekop Fortress was probably long gone as a defensive entity by this point, Perekopskiy Val was still a defensible obstacle that could be utilized against those wishing to head into the Crimea via the Isthmus of Perekop, and White General Yakov Aleksandrovich Slashchev-Krymsky (1885-1929) managed to build up some "light barriers" along the ditch, centered on a few artillery pieces.

|

Light as those barriers may have been, they were heavy enough to prevent the Reds from breaking through in a meaningful fashion in March of 1920.

By the time the Red Army returned with a significantly larger force the following November, much of Perekopskiy Val had been fortified with supporting trenches, several lines of barbed wire and machine guns covering the 8-meter-high walls that the Turks had built...but the Reds weren't taking no for an answer this time around, and the shaft was captured by the Red Army's 51st Infantry Division (full name: 51st Rifle Perekop Order of Lenin Red Banner Division named after the Moscow Council of Workers' Peasants and Red Army Deputies) on November 9, 1920. The Reds made short work of the Whites in Crimea after that, and by the end of November the Crimea was fully red in hue, likely in more ways than one.

|

|

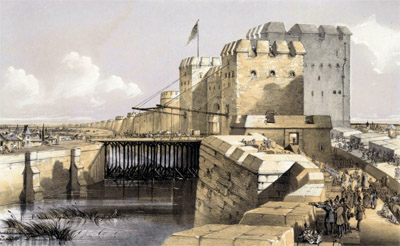

It wasn't always just a strategically-shaped hole in the ground! Perekop: The Golden Gate, Fortalice & Ditch, a lithograph by T. Packer, 1855. This image comes to us courtesy of the Institut Cartogràfic i Geològic de Catalunya. Thank you, Institut Cartogràfic i Geològic de Catalunya. Assumedly, this majestic image came into existence thanks to interest in the region due to the Crimean War...but based on the history that I've found, Perekop Fortress would have looked absolutely nothing like this sleek, impregnable monster of loveliness in 1855. |

|

If you thought Perekopskiy Val and Perekop Fortress were dilapidated at the end of the 19th century, just imagine how they must have looked after the Red Army rolled over them in 1920! Still, some sort of defense had to be cobbled together on the Isthmus of Perekop in the autumn of 1941, because here came the Nazis, along with some Romanian units, to conquer the Crimea.

|

A "preserved" section of Perekopskiy Val as it appears today. I still wouldn't wish to attempt to drive a tank over this obstacle! |

|

The Red Army did much of the defense of the isthmus in and around the city of Perekop, using the Perekopskiy Val as a fallback position, but the combined weight of German airpower, artillery, armor and infantry (and let us not forget the doubtlessly invaluable contributions of the Romanians) were too much for the Russians, and the isthmus was German property by the end of October 1941.

Perekopskiy Val was used as a defensive structure by folks attempting to halt an invasion of the Crimea yet again in the Spring of 1944, but this time it was the Germans and Romanians who manned the Turkish wall! The Red Army was by this point an unstoppable juggernaut, however, and no amount of deft German defensive engineering could stop it. |

|

|

The Nazis may have left behind the most compelling legacy of all who fought and died along the Perekopskiy Val, in the form of hundreds of thousands of landmines, which are still being discovered today. The graves of men who died fighting over the shaft from the 16th through 20th centuries are all over the area, and you can't go digging in or around the shaft without coming across their remains...if you haven't already been atomized by a 70-year-old German mine.

|

In 1950, the Soviet Union committed to building the North Crimean Canal, which would bring water from the Dnieper River in the Ukraine all the way to Kerch at the Crimea's far eastern extent, leaving reservoirs along the way for agricultural irrigation. By necessity this canal had to cut through Perekopskiy Val, and it can presently be seen as a diagonal slash to the east of the ditch's center. From 1961 to 1963 thousands of German mines were cleared from the area surrounding the Val to make way for the canal, which was ultimately completed in 1971.

When the Soviet Union imploded in 1991, the Crimea became part of the new Ukrainian Republic.

|

|

The mighty Golden Gate to the Crimea, Perekop Fortress, in what is probably a much more accurate portrayal than the one earlier on this page. This one is by Carlo Bossoli, 1856. The mighty Golden Gate to the Crimea, Perekop Fortress, in what is probably a much more accurate portrayal than the one earlier on this page. This one is by Carlo Bossoli, 1856. |

|

Which would be pretty much where things stand today, had Russia not annexed the Crimea, again, in 2014. While this move probably seems perfectly reasonable to most Russians, the rest of the world has agreed that it is not, in fact, reasonable. Citing a huge outstanding debt for previously-provided Dnieper water, the Ukraine cut off waterflow to the North Crimean Canal following the annexation, and the canal is little more than an ugly, dry shaft that cuts through the lovely, equally dry Perekopskiy Val today.

Since 2014 Russia has invested heavily in Crimean infrastructure, including the construction of a high-tech security fence to protect the Crimea's new border with Ukraine...which, tragically, is about four miles north of Perekopskiy Val. How cool would that have been, a 21st century security fence atop a 16th century Turkish wall?

Muchas gracias to ever-vigilant starfort discoverer Nico Pfeifler, who alerted us to Perekop Fortress and its attendant heroic ditch!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|