|

Castillo de San Carlos de la Barra

Island of San Carlos, Zulia, Venezuela

|

|

|

Constructed: 1623

Used by: Spain, Venezuela

Conflicts in which it participated:

Anti-Pirate Shenanigans,

Venezuelan War of Independence,

Venezuelan Crisis of 1902-1903

|

Though completely incapable of defending itself from the invaders against which it had been intended, the Castillo de San Carlos de la Barra holds the distinction of being the only starfort in history to deflect the Imperial German Navy!

The Añu tribe that inhabited the west coast of what would be named Lake Maracaibo got their first glimpse of pale, diseased Europeans in 1499. The city that would become Maracaibo began the lengthy "founding" process in 1529.

|

|

|

|

Lengthy, because the town was "founded" on three occasions! First in 1529 by the German Welser family, which had been granted rights to do as they pleased in Spain's new colony in Venezuela (read more about this financial weirdness on our Castillo San Felipe page if you're interested). They evacuated the area in 1535, due to "lack of activity in the zone." A second attempt to colonize this seemingly choice spot was made by Spain a few years later, but it wasn't until 1574, when a Captain Pedro Maldonado finally founded Nueva Zamora de Maracaibo, that the "founding" stuck.

|

Clearly, there was once a moat surrounding the Castillo. You'll find that, today, most places that used to have moats no longer have water in them, for wet moats are stinky. Clearly, there was once a moat surrounding the Castillo. You'll find that, today, most places that used to have moats no longer have water in them, for wet moats are stinky. |

|

Pirates enjoyed the Caribbean, and liked Maracaibo. A lot. So much so that they began attacking and plundering the town in 1614. Between then and 1678, Maracaibo had been attacked and pillaged by freebooters, corsairs, filibusters and whathaveyous five times.

In order to get into Lake Maracaibo, one must cross dangerous shoals, past the island of San Carlos. That this was an ideal spot for a starfort was not lost on the Spanish authorities. The Castillo de San Carlos de la Barra was built at this chokepoint in 1623, with limestone brought from nearby Toas Island. The fort mounted sixteen guns. |

|

For whom was the Castillo de San Carlos de la Barra named? Obviously somebody saintly named Charles, except the king of Spain in 1623 was good ole Philip IV (1605-1665): There had been a King Charles previously, but he had abdicated in 1556. Were there people in charge of naming things in 1623 who still had fond memories of Charles I (1500-1558)? Maybe, but one of the surest ways of getting one's head removed from one's body in 17th century Spain would have been by saying nice things about any king other than one's current king. Assumedly the island on which the Castillo was built was named during the Charles I administration, and the fort was just named for its location. The rest of the fort's name is more easily explained: The shoals at the mouth of Lake Maracaibo are also called the bar, hence de la Barra.

|

In 1666, a pirate fleet of 8 ships and 650 men exchanged gunfire with the Castillo for three hours, then landed and took possession of the fort. An impressive maiden effort there, Castillo.

A similar situation occurred three years later, when the Castillo again failed to prevent pirates from sacking Maracaibo. The pirates, led by Welshman and future admiral of the British Navy Sir Henry Morgan (1635-1688), got past the fort with little in the way of difficulty and went about their plundering business. When it became time to depart from Lake Maracaibo, however, folks from the town had fled to the Castillo, which may have been indifferently crewed when the pirates passed it on the way in, but was now fully manned, its sixteen guns ready and waiting to pound the pirate fleet to flinders.

|

|

The Castillo's rather unsavory-looking front gate. Surely it appeared more formidable in the 17th century. |

|

But the clever Sir Henry outfoxed the Castillo's defenders. Seeing that the pirates were sending a party ashore to attack the fort from the landward side, the Spaniards laboriously dragged the Castillo's guns around to face that direction. By the time it was revealed that the land attack had been a ruse, the pirate ships were sailing through the shoals on their way out of Lake Maracaibo, doubtless flashing their bare behinds at the Castillo, whose defenders had no time to reorient their cannon. Britain (and by Britain I of course mean piracy) triumphs again.

Notwithstanding their inability to build a fort capable of deterring pirates, the Spanish Empire in South America continued, fat and happy, until the beginning of the 19th century. When the armies of Napoleon (1769-1821) effectively invaded Spain in 1807, however, the subjected peoples of South America grabbed their chance.

|

The Battle of Lake Maracaibo by José María Espinosa Prieto (1796-1883), who obviously never actually saw the Castillo, portraying it as a squatty Martello Tower. The Battle of Lake Maracaibo by José María Espinosa Prieto (1796-1883), who obviously never actually saw the Castillo, portraying it as a squatty Martello Tower. |

|

Occupied with trouble at home, Spain was unable to quash numerous rebellions sprouting in their South American colonies. One of these became the Venezuelan War of Independence, which began in 1811.

The Battle of Carabobo (1821) was pretty much the culmination of this conflict, with the Royalist forces all but crushed, but Spain still held a few key positions in Venezuela. Such as the Castillo de San Carlos de la Barra.

In July of 1823 the Spanish and Republican fleets gathered in Lake Maracaibo to pound on one another. Had the Spanish Navy been victorious, it could have led to a resurgence of Spanish power in Venezuela. As you have no doubt guessed from my choice of words, this was not to be. |

|

The Venezuelan War of Independence had killed a reported half of Venezuela's caucasian population, though it was surely a consolation that they had the awesomeness of the Castillo de San Carlos de la Barra to cheer them up. Fortunately if inexplicably, the Castillo was not renamed something like La Fortaleza de la Felicidad de Liberación Gloriosa Victoria (The Fortress of the Glorious Liberation Victory Happiness) by its new owners. Which is what I would have done.

|

Venezuela's troubles with European powers were by no means over. From 1859 to 1863, a vicious Venezuelan Civil War was fought betwixt liberal and conservative factions. This in turn led to a series of smaller civil wars, with various dudes grabbing for the brass ring of power. European nations, primarily Germany but also Great Britain, Italy and Holland had made substantial investments in Venezuela, which were effectively lost in the wars.

Further investor outrage occurred when Cipriano Castro (1858-1924) seized power in 1899, made himself dictator and defaulted on all foreign debts. Castro's nerviness in this regard was due to a misplaced Venezuelan expectation of American protection.

|

|

|

|

US President James Monroe (1758-1831) had in 1823 declared; ...the American continents...are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers. This wasn't a suggestion that anyone took all that seriously in 1823, when the United States had no navy capable of defending the entire hemisphere from the desires of Europe, but by the end of the 19th century it had taken on a new meaning. For it was because he was feeling snug and secure behind the Monroe Doctrine and the US Navy, which had effortlessly humbled that of Spain in the Spanish-American War (1898), that Castro was confident enough to thumb his nose at Europe. US President Theodore Roosevelt (1858-1919), however, had a different interpretation of the Monroe Doctrine than did Cipriano Castro. "We do not guarantee any state against punishment if it misconducts itself," said Roosevelt. Which led to the Venezuelan Crisis of 1902-1903. Germany, Great Britain and Italy sent naval contingents to Venezuela to punish the nation for its debts. The tiny Venezuelan Navy was done away with in short order, and the allied nations began blockading Venezuelan ports. Visit our Castillo San Felipe page to read about the only thing that the German and British navies ever simultaneously shelled! |

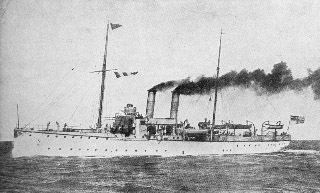

SMS Panther of the Kaiserliche Marine. Launched in 1901, the Panther participated in several of Germany's imperialism-projecting festivities of the early 20th century. SMS Panther of the Kaiserliche Marine. Launched in 1901, the Panther participated in several of Germany's imperialism-projecting festivities of the early 20th century. |

|

On station in the Gulf of Venezuela on January 17, 1903 were the German gunboat SMS Panther and light cruiser SMS Falke. A feisty merchant schooner eluded the blockade and slipped into Lake Maracaibo, its captain obviously familiar with the shallow waters of the lake's entrance. The Panther took off in hot pursuit, but became predictably stuck on the sandbanks.

Which put it right in front of the starfort of our current interest! The Castillo opened fire with four guns, one of which being an 80mm Krupp gun (ironically, Krupp is a German manufacturer: The mount for this gun can be seen near the center top of the first image on this page), which was used to good effect against the Panther. The ship and the Castillo traded shots for 30 minutes. |

|

The Panther was "considerably damaged" in this exchange, but managed to get itself free of the obstruction and limp out of range of the Castillo's guns. The Castillo was reportedly undamaged, though three of its defenders were wounded. For the first (and likely last) time in history, a starfort had bested a world-class, 20th century navy!

|

For exactly three days. On January 20th, the German protected cruiser SMS Vineta took a break from pounding the snot out of the Castillo San Felipe and, along with the Panther, commenced pounding the Castillo de San Carlos de la Barra instead. The 8-hour bombardment that followed reduced the Castillo and surrounding area to burning ruins, killing around 40 people, 25 of whom were civilians. By February of 1903, the European fleets had steamed back across the Atlantic, having made their point, and having noted that Teddy Roosevelt was getting tired of their presence. |

|

Today, the Castillo de San Carlos de la Barra heroically protects four interior trees. |

|

Once repaired, the Castillo served as a prison for anyone who pronounced the name "Cipriano Castro" with anything less than the servile gravity that it demanded. In 1965 the fort was declared a National Historic Monument, whereupon its rotting prisoners were assumedly shuffled elsewhere.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|