|

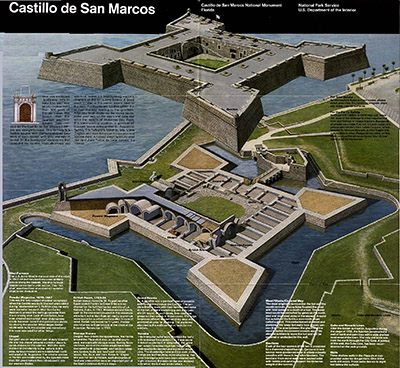

Castillo de San Marcos

St. Augustine, Florida, USA

|

|

|

Constructed: 1672 - 1696

Used by: Spain, Great Britain, USA

Conflicts in which it participated:

Queen Anne's War, War of Jenkin's Ear

Also known as: Fort St. Mark, Fort Marion

|

The area that is now St. Augustine was first explored by Ponce de Leon (1474-1521) in 1513: Naturally, he claimed it for Spain. Several failed attempts at the colonization of Florida followed over the next few decades by both France and Spain: The most painful being a colony of 250 French Huguenots who built themselves a lovely little starfort in 1562, only to be evicted (and slaughtered) by the Spaniards, which process eventually resulted in the razing of the fort. Read more about this happy story at our Fort Caroline page! |

|

|

|

The Spanish, those jealous landlords, founded the city of Saint Augustine in 1565. They built a series of nine wooden forts to defend their city over the next hundred years, but after a costly attack by English buccaneer Robert Searle in 1668 (and the foundation of Charlestown by the British in 1670, just two day's sail from St. Augustine) Mariana (1634-1696), Queen Regent of Spain, ordered that a proper fort be built to protect her colonial holding.

Work began on the Castillo de San Marcos in 1672. Workers were brought in from Havana to build the fort out of Coquina, a local limestone comprised of the shells of billions of teeny clamlets. Labor for the fort's construction included Spaniards and Indians, plus "some" convicts and slaves. Construction was completed in 1696.

|

Quarrymen in 1671, collecting Coquina stone for the Castillo. |

|

A British fleet from Carolina Province (a British colony centered on modern Jacksonville, Florida) sailed into St. Augustine's bay in November 1702, hoping to capture the city. The Castillo's 300 soldiers and St. Augustine's 1200 residents all took refuge in the fort, where they withstood a British siege for two months. The Castillo's teeny clamlet walls proved more than a match for British naval firepower, and the fort suffered very little damage. A Spanish fleet from Havana Cuba arrived in January 1703 and trapped the British fleet in the bay. The British were forced to burn their ships to prevent them from falling into Spanish hands, but also managed to burn down St. Augustine before marching back to Carolina. |

|

|

The interior of the Castillo was rebuilt starting in 1738, replacing the wooden ceilings with vaulted ceilings, adding more defense against bombardment and allowing cannon to be placed along the fort's walls, instead of just at the corner bastions. These improvements proved fortuitous when the British declared war on Spain in 1739 (the War of Jenkin's Ear (1739-1748) came about thanks to Spain and Great Britain bumping into each other in the New World a few too many times) and a fleet commanded by General John Oglethorpe (1696-1785) sailed back into St. Augustine's bay in 1740, sending the city's 1300 residents back into the Castillo...again, British guns made no demonstrable effect on the fort's walls. General John tried to starve the Spanish out, but his fleet was low on both supplies and morale, so the British left, unsuccessful, once again.

|

The Treaty of Paris that concluded the Seven Years War (1756-1763) finally provided Great Britain that which it couldn't achieve by force of arms: The Castillo de San Marcos! All of Florida was now Britain's domain, in exchange for returning Havana and Manila to Spain. The Castillo was officially turned over to the British on July 21 1763. The name of the fort was changed to Fort St. Mark, and wasn't maintained, as Britain faced no enemies in the region.

...until the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783)! St. Augustine became the capitol of the British colony of East Florida, and Fort St. Mark the base of operations for British military operations in the south. More improvements were made in the fort's interior. |

|

A pamphlet handed to those fortunate enough to pay to get ino the Castillo de San Marcos! Click on it, it's huge. |

|

|

The Castillo was mostly used as a prison during the war, holding prisoners that were taken when the British captured Charleston (and most of the southern Continental Army) on May 12 1780. Fort St. Mark didn't play much more of a role in the conflict thanks to the efforts of Bernardo de Galvez (1746-1786), the governor of Spanish Louisiana, who kept the British too busy to mount many offensives against its wayward colonists by capturing several British-held cities, tying down loads of British troops in the process. The Second Treaty of Paris (1783), which ended the American Revolution, returned Florida to Spain. Spanish troops moved back in to the once again properly-named Castillo on July 12 1784.

The Spaniards continued to improve the Castillo, but didn't get the opportunity to chortle over their reacquisition of Florida for long. Most of the Spanish colonists in Florida had left during the period of British rule, and the new English settlers in the region didn't care for their new government. That and pressure from the rapidly expanding United States led to the Adams-Onis Treaty of 1819, which handed Florida over to the US, in addition to settling some border issues in Texas and the Rocky Mountains.

|

The United States takes possession of the Castillo de San Marcos: July 10, 1821. Click on it, it's ever so slightly larger. |

|

The Americans renamed the Castillo as Fort Marion, after US Revolutionary War hero Francis "The Swamp Fox" Marion (1732-1795), whose guerilla tactics were the terror of British forces in South Carolina. Job #1 for the US at their new fort was to imprison Indians, as the Seminole Wars (1814-1858) were producing lots of red-skinned dudes in need of incarceration. The Seminole Wars turned out to be the most expensive endeavor in which the young United States had involved itself, and in the end the Seminoles burrowed into the Everglades and there they remain, undefeated and belligerent to this day.

|

|

At the outset of the US Civil War (1861-1865) Federal forces had long ago withdrawn from Fort Marion, leaving a single man behind to act as a caretaker. Confederate troops marched up in January of 1861 to claim the fort, but that one Union sergeant refused to surrender it unless given a signed receipt by the Confederacy.

One wonders at both the concept of leaving one guy behind at a fort that the Confederates would surely come to claim (although this turns out to be not terribly unusual: There were plenty of awesome starforts up and down the coasts of the southern United States that were so individually manned at the start of the Civil War) and why those Confederates would be reluctant to just knock the guy on the head, but a signed receipt was duly produced, and Fort Marion was handed over to the Confederacy.

|

Most of the fort's cannon were soon dispersed to other places, leaving it somewhat defenseless. The steam frigate USS Wabash entered the bay on March 11 1862, finding the city of St. Augustine bereft of any Confederate defenders and Fort Marion deserted, so city and fort were taken back by the Union without so much as a scabbed knee to the federal government.

By 1875, many Native Americans were again incarcerated at Fort Marion, this time from tribes of the western United States. Northerners vacationing in St. Augustine took an interest in educating and converting these luckless heathens to Christianity and American society in general, going so far as to send some 20 of them to college upon their release. |

|

The USS Wabash, a steam screw frigate of the US Navy, was launched on August 18, 1855. Steam and sails?? I don't believe you. |

|

|

1898 saw the incarceration of over 200 deserters from the Spanish-American War (1898). By the time these prisoners had moved on in 1900, Fort Marion was taken off the active duty rolls and ceased to be a military facility.

Fort Marion was named a National Monument in 1924, and handed over to the National Park Service in 1933. In 1942 everyone wised up and realized that Castillo de San Marcos is a way cooler name, and the name Fort Marion was left on the junk heap of history. Today, the fort is not only a popular tourist attraction but THE tourist attraction of St. Augustine.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|