|

Fort Senneville

Senneville, Quebec, Canada

|

|

|

Built: 1671, 1692, 1702-1703

Destroyed: 1691, 1776

Used by: France, Great Britain

Conflict in which it participated:

Iroquois Incursions, American Revolutionary War

|

In the last decades of the 17th century, Canada, or at least those portions of it that had been explored by Europeans, was French. The riches of the new world flowed back to the mother country, and the most valuable of those riches were furs: Countless Canadian beavers willingly gave their semiaquatic rodent lives so that the ladies and gentlemen of Paris could wear the finest hats and cloaks in the world. |

|

|

|

Intrepid French exporer Jacques Cartier (1491-1557) was the first European to see the Iroquois town of Hochelaga in October of 1535. This impressive metropolis, at which over a thousand locals showed up to ogle Cartier's ship, would become the even more impressive metropolis of Montreal. Samuel de Champlain (1567-1635) returned in 1603, and found this formerly bustling burg to be mysteriously vacant: Intertribal wars and nasty diseases provided by Europeans had done an impressive job of emptying this really quite desirable location. Champlain set up a fur trading post on what he named La Place Royale in 1611, which we now know as the Island of Montreal.

|

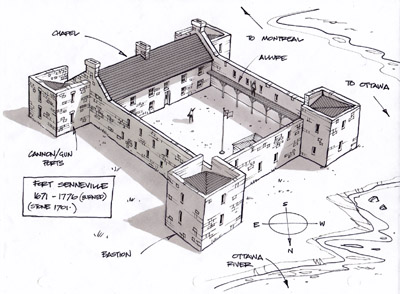

Fort Senneville was initially a wooden fort, but was upgraded to stone in 1701. This image comes to us courtesy of OttowaRewind.com, a truly fascinating blog about cool Canadian things! Fort Senneville was initially a wooden fort, but was upgraded to stone in 1701. This image comes to us courtesy of OttowaRewind.com, a truly fascinating blog about cool Canadian things! |

|

It's probably safe to say that Canada wouldn't have grown the way it did, had it not been for the St. Lawrence River. All of the cities that figured into Canada's early days are either on the St. Lawrence (Quebec, Montreal, Kingston), on one of its tributaries (Ottowa) or on one of the Great Lakes (Toronto), which is connected to the wider world by the St. Lawrence.

Being on this riverine highway, Montreal grew swiftly, and was just as swiftly recognized to need defendin' from the local Iroquois, who weren't quite as ready to completely abandon the region as the Canadiens may have wished. Eventually a string of 30ish forts were built to protect Montreal: Most of these were relatively insubstantial wood, but at least one got a stone overhaul.

|

|

|

Fort Senneville was initially erected in 1671 as a lovely wooden stockade fort, to protect a fur trading post nearby. Jacques Le Ber (1633-1706), the influential fur trader who owned this part of the Island of Montreal (and whose fur trade was being protected by Fort Senneville) reasoned that further fortification of the masonry variety was needed, so a stone windmill was built on a hill close to the fort in 1686. A windmill, one might ask? This windmill sounds as though it was a low-level Martello Tower in that it served as a watchtower, had square loopholes for muskets and supported machicolation: A system by which unpleasant things could be conveniently dumped onto the unsuspecting heads of attackers who were so unwise as to pass underneath. This fortified windmill concept was a new one, and Fort Senneville's sentinel windmill was unique until another similar specimen was built elsewhere in Quebec. The Indians may or may not have felt that Fort Senneville (which Le Ber named after his hometown of Senneville-sur-Fécamp, France) was a threat, but a stone windmill was another matter entirely, and fort and windmill were duly attacked in 1687: A few settlers were killed in this attack, but the Indians were repulsed. They returned in 1691, however, and were more successful in that they burned down Fort Senneville. Though damaged, the mighty windmill still stood, which served as a testament to the superiority of stone as a building material for forts, in case anyone had been unconvinced.

|

Louis de Buade de Frontenac (1622-1698), Governor of New France (1672-1682, 1689-1698), ordered Fort Senneville reconstructed, but wished that it would be made to last this time around. In 1692, our fort was rebuilt with stone, and four walls with a bastion at each corner made it a bonafide starfort!

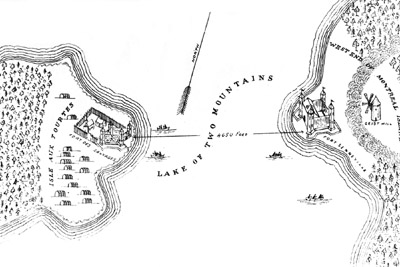

At or around 1725, another fort was built across the water from Fort Senneville on the Isle aux Tourtes (Island of Ties? Neckties?). The island was established as a community of Indians of the Nepissingue Nation, whose souls were in need of saving by the missionaries who ran the island, but whose energies were more directed toward the fur trade. This community built a wooden fort, which at least in some instances was known as Fort des Savauges. |

|

The Lake of Two Mountains is where the St. Lawrence, Ottowa, Prairies and Mille îles Rivers meet. Facing Fort Senneville across this waterway was, for a brief period, the Fort of the Savages...which the Indians probably called something else. The Lake of Two Mountains is where the St. Lawrence, Ottowa, Prairies and Mille îles Rivers meet. Facing Fort Senneville across this waterway was, for a brief period, the Fort of the Savages...which the Indians probably called something else. |

|

Details about the Fort of the Savages are sketchy, and there's certainly no trace of it left today: See? Wood vs. stone! Now are you convinced?!

The new Fort Senneville clearly impressed someone, because it was never attacked by Indians again. Buildings were added to the fort's interior steadily over the next few decades, making it both the most secure and comfiest fur trading post this side o' the Pecos. Perhaps if more of France's forts in Canada had been as stoutly built as Fort Senneville, they wouldn't have had to hand over all of Canada to the United Kingdom at the conclusion of the Seven Years' War (1756-1763). This of course included Fort Senneville, which must not have made much of an impression on its new owners because the British never manned it.

When Canada was French the British wanted it, and when it was British the Americans wanted it. One of the first priorities America had once the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) kicked off was invading Canada, and at the head of this onslaught was American Brigadier General Benedict Arnold (1741-1801).

|

What was left of Fort Senneville after Benedict Arnold got through with it. What was left of Fort Senneville after Benedict Arnold got through with it. |

|

Though today universally recognized as the textbook definition of perfidy for his treachery later in the war, Arnold spent most of the Revolution being an extremely effective American leader. After capturing Fort Ticonderoga in May of 1775, he led a force into Quebec, where his and another force led by the later-to-be-namesake of Fort Montgomery, Richard Montgomery (1738-1775), captured Montreal. British forces ground their way east toward Montreal and made it to Fort Senneville in May of 1776, but a series of maneuvers left the fort empty, and shortly thereafter Arnold ordered its destruction: Our heroic little fort was demolished. |

|

|

The Americans fled from Canada, but the war, and everything else, was over for Fort Senneville. As Montreal developed into a major metropolis, the western end of the island became suburbs for the well-to-do. The property that included the remains of Fort Senneville were purchased by John Abbott (1821-1893): Abbott would serve as a Member of Parliament, Mayor of Montreal and Prime Minister of Canada, though not simultaneously. Abbot bought Fort Senneville in 1865, when he was the commander of the 11th Battalion Volunteer Militia Infantry of Canada, also known as the Argenteuil Rangers. Other rich and powerful persons have owned the property every since, and though it was classified as a site historique in 2003 and Canada's Ministry of Culture and Communication funded some archaeological research and repairs to the fort, Fort Senneville remains on private property, visible only to those who squint at Google Earth.

Ten thousand thanks to Vince Rioux, who alerted us to the existence Fort Senneville!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|