|

Vyšehrad

Prague, Czech Republic

|

|

|

Constructed: 1653-1727

Used by: Austria, France, Prussia

Conflicts in which it participated:

Occupied, but never attacked

|

Today's Czech Republic is based on the boundaries of Bohemia, which existed from the 11th into the 19th century as part of the Holy Roman Empire. Bohemia got its name from the city of Boihaem, founded circa 1306BC by King Boyya. Later residents of this city renamed it Bohemia, "home of the Boii people" (where the Grrl people lived is an open question).

This city became Prague, thanks to a castle named Praha built on a hill at its northeastern boundary. That structure is now known as Prague Castle, the construction of which began in 870AD.

|

|

|

|

Everybody likes a new castle, but a semi-mythical prince by the name of Krok wasn't convinced that Praha was situated in the optimal location. Prince Krok ordered that the forest atop a steep rock hill on the other bank of the Vltava River be cleared and a castle be built there: Vyšehrad was thus born, in the mid-10th century.

Fantastic, two strong fortifications, sited at strategic points north and south of the city, on either side of the river! Prague will be the safest city in the world with these two forts working together in its defense, right? Somehow, it didn't work out that way: Royal opinion favored either Prague Castle or Vyšehrad over the years, but seldom both of them simultaneously.

|

Prague Castle in 1607 at the top (...where? It's there, I promise), and today. There are four churches packed into the Prague Castle complex, but that big black thing towards the rear, the St. Vitus Cathedral, is the big daddy of 'em all. No offense Prague Castle, but you are no starfort. Prague Castle in 1607 at the top (...where? It's there, I promise), and today. There are four churches packed into the Prague Castle complex, but that big black thing towards the rear, the St. Vitus Cathedral, is the big daddy of 'em all. No offense Prague Castle, but you are no starfort. |

|

The precise date that Vyšehrad sprang into existence is a bit murky, but the fort was referenced on coins minted under the administrations of Princes Bolesac I, II and III, which period spanned the last half of the 10th century...and, documentation exists saying that a bell was rung at Vyšehrad in 1004 as a signal to expel the Poles from Prague. Which sounds bad, but who knows what those sneaky Poles had been up to.

The first king to forego the pleasures of Prague Castle and move his royal self to Vyšehrad was Vratislav II (1031-1092), which occurred around 1070. Vratislav had had a disagreement with his brother and fellow castle resident Bishop Jaromír (1040-1090), who appears to have been a bit of a weenie. The king not only moved to Vyšehrad, but also enriched it with a new, well-funded church in order to limit his weeniebro's influence. Vratislav II ordered the construction of St. Martin's Rotunda towards the end of the 11th century. Little of Vyšehrad remains from this period, but this rotunda is still rotunding merrily away!

Vyšehrad was the seat of Czech monarchs until 1140, whereupon Prague Castle reasserted itself as Place For Kings To Be. Our pre-starfort began to crumble away, though the chapter of priests that Vratislav II had initiated therein continued to prosper. |

|

The Chapter, as the wealthy priests stationed at Vyšehrad were known, spent much of the 13th and 14th centuries building nice churches in the fortified area, and King Charles IV (1316-1378) proved to be a particular devotee to the well-being of our fortification...even though he was way too busy to reside there. All of Prague was improved during Charles' reign, and new battlements around our fort were joined to the new city walls.

But city walls mean nothing to Hussites, particularly when they're already in Prague! The Hussites were holy warriors of a proto-Protestant reformation that took place in and around Bohemia in the early-mid-15th century. The Hussite Wars (1420-1434) began in Prague and spread outward, but one of the first things the Hussites did was besiege and capture Vyšehrad, in November of 1420. Our somewhat dilapidated fort was handed back over to royal forces not long after, but it had been so thoroughly pillaged that it was inhabited by poor craftsmen after the war. Vyšehrad became a small hilltop town, and some sort of small fortification was built therein.

|

Primarily Protestant Prague yet again found itself the genesis of a major conflict in 1618 when Catholics, who had attempted to dismiss Protestant governmental officials, were thrown out of a window, which caused them to die. This event is known as the Second Defenestration of Prague (the first such defenestration began the Hussite Wars), which is a better name than That Time Some Guys Threw Some Other Guys Out of Windows. This august event (a bit of a Prague tradition, it seems) kicked off the Thirty Years' War...which was unpleasant by most measures, but was a boon to the art of starfortery.

Over the course of the war, "loose" starfort bastions were added to Vyšehrad's "endangered places": These would have been essentially freestanding ravelins, built in front of the fort's gates.

Another fortification that did not undergo this emergency starfortification process was Prague Castle. In 1648, while the negotiations to end the Thirty Years' War were proceeding, the Swedes took advantage of everybody's stupid postwar optimism and attacked Prague.

|

|

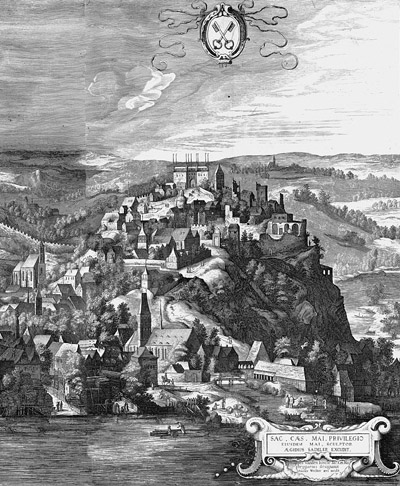

Vyšehrad at the beginning of the 17th century, At the top is The Chapter's coat of arms (coat o' keys). Their motto: Don't worry, God, WE'VE got the keys! Vyšehrad at the beginning of the 17th century, At the top is The Chapter's coat of arms (coat o' keys). Their motto: Don't worry, God, WE'VE got the keys! |

|

A major part of the Swedes' strategic goal was to steal the valuable art collection of Holy Roman Emperor Rudolph II (1552-1612), which was stored at Prague Castle. No starfort bastions were there to deter them, and they made off with the pick of Rudolph's collection (Rudolph probably wasn't too bothered by the theft, as he had been dead for 36 years). Interestingly, this turned out to be the last hostile act of the continent-spanning Thirty Years' War, which had both begun and ended in Prague.

The population of the little town that had sprouted in Vyšehrad prior to the Thirty Years' War dwindled during that conflict, and the town was razed in the early 1650's in order to get down to some serious starforting: The Chapter was even expelled from the premises for a lengthy period. Vyšehrad's present irregular, five-bastioned trace came into being at this time. A sixth bastion was at least partially built directly facing the river...at least it was built enough to be named, but it has since wandered off to seek its fortune elsewhere.

|

The names of Vyšehrad's five bastions, plus that phantom bastion to the west that may or may not have ever existed, but it got a name and a number anyway! Perhaps this was intended to keep enemies wondering as to just how many bastions Prague really had at its disposal. The names of Vyšehrad's five bastions, plus that phantom bastion to the west that may or may not have ever existed, but it got a name and a number anyway! Perhaps this was intended to keep enemies wondering as to just how many bastions Prague really had at its disposal. |

|

As was standard practice for devout, starfort-buildin' monarchies, Vyšehrad's bastions were named after saints: Weirdly, two of the bastions were named for two saints?! Well, if each saint is thought to provide protection in one particular area, then mixing & matching one's saints surely makes a super power? Vyšehrad's bastions were named St. Bernard; St. Paul/Roch; St. Peter/Agnes; St. Ludmila; St. Wenceslas; and St. Leopold. These perfectly serviceable names were later replaced by soulless numbers as part of the Prague Fortress System.

Vyšehrad's walls were from 42 to nearly 60 feet in height, and eight to 16 feet in thickness. This is naturally a casemated fortification, with various strategically-placed ramps with which artillery would have been positioned. Housing for the number of soldiers that would need to sleep somewhere when the fort was fully garrisoned were not included within the fort: Those guys would have had to find a bed someplace in town. |

|

Sadly, Vyšehrad was never called upon to defend Prague in any meaningful way. The War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748) brought French troops to both Prague and the starfort of our current interest in 1741, and the French were always happy to upgrade whatever starfortery they occupied, however briefly (in this case, less than a year). The Leopold Gate in Vyšehrad's southeast curtain wall is also known as The French Gate, so one suspects that they may have had something to do with it.

Prussian troops were the next foreign folks to enjoy the pleasure of occupying Vyšehrad for about ten weeks in 1744. They made an attempt to destroy the fort with explosives before leaving, but locals extinguished the fuses on three separate occasions, at which point the Prussians either ran out of fuses, or just figured it wasn't worth the effort: It should be noted that by this time everyone recognized that Vyšehrad was poorly sited to function as a defensive fortification for Prague. Nearby higher ground offered plenty of opportunities of an artilleristic nature for any attacker. Could it be that Prince Krok hadn't taken the not-yet-extant concept of artillery into account when he chose the site for Vyšehrad in the mid-10th century?!?

|

Despite this universal understanding, Vyšehrad was further enhanced in the years following the French Revolutionary Wars (1799-1815). The Revolution of 1848, in which populations over much of Europe rebelled against their increasingly disfunctional imperial masters, touched Prague in June of that year. For five days, fighting was fierce at barricades in Prague's streets, until royal forces determined that the best course of action was to withdraw and bombard the old town from across the Vltava River. This tactic cooled the revolutionists' ardor pretty quickly, by killing them. |

|

Vyšehrad from the south. Thanks once again, Google Earth! Vyšehrad from the south. Thanks once again, Google Earth! |

|

The various uprisings of 1848 were put down mercilessly wherever they occurred. The Habsburg authorities in Prague took steps to proactively deal with any future such tomfoolery by placing artillery on Vyšehrad's Battery No. 38 (also known as the St. Leopold Bastion) that was intended not to defend Prague from attackers, but to pummel Prague's potentially rebellious inhabitants from within. Similar batteries were set up at two other locations in Prague.

The American Civil War (1861-1865) and Austro-Prussian War (1866) further demonstrated to anyone paying attention the inability of the classic starfort to adequately defend the city which it had been built to defend, much less defend itself, from modern artillery. The Habsburgs threw up their hands and sold Vyšehrad to local government. Prague's walls began to come down in 1875, but Vyšehrad remained a more or less intact, military-operated edifice until 1911, when it was handed over to the city, to do with it what they would.

The early 20th century saw the Austro-Hungarian Empire finally put to rest at the end of the First World War (1914-1918), whereupon Czechoslovakia became a nation, with its capital in Prague...and good ol' Prague Castle as its seat of government.

|

After 1866, Vyšehrad's Basilica of Peter and Paul was rebuilt to the state of horrifying yet pleasing gothic blackness that we see today, and its graveyard developed into a who's-who of famous Czech persons...which is of course a list of famous Czech persons of whom I've never heard, except for composer Antonín Dvořák (1841-1904), of whom I have heard.

There is a legend regarding Vyšehrad. It is said that deep in the rock beneath Vyšehrad there is a vault, crammed with untold riches. This vault is watched over by an "old Czech lion," with twelve cubs. Several times a year, the lion ascends to see if there is any danger to the Czech Republic: If all is well, Mr. (Mrs?) Lion returns to his (/her?) lair, content. If danger is imminent, however, the lion roars so powerfully that the rock beneath Vyšehrad shatters, releasing the twelve cubs, which would assumedly proceed to deal with whatever is troubling the Czechs. Unfortunately, the lion appears to have been on vacation in 1939 when the Nazis showed up.

|

|

St. Martin's Rotunda, visiting us from the 11th century! St. Martin's Rotunda, visiting us from the 11th century! |

|

Today, Vyšehrad is a pleasant, well-cared-for green space filled with statues, churches, gardens and cool old buildings. Many thanks to the starfort enthusiast and Prague resident who alerted me to Vyšehrad in March of 2019...unfortunately my email doesn't want to show me anything from that long ago, so I don't remember the guy's name!!! Hit me again if you would, good sir, so I can thank you properly!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|