|

Fort Loudoun

Vonore, Tennessee, USA

|

|

|

Constructed: 1756

Razed: 1760

Reconstructed: 1930's-1960's

Used by: Great Britain

Conflict in which it participated:

French & Indian War

|

|

|

|

|

The Cherokee people lived in the area that is now southeastern Tennessee, and in the 18th century were increasingly pulled betwixt the competing interests of the French and the English. The native persons would of course do what was best for their tribe, which often came down to predicting which set of evil white men would be victorious in whatever conflict was presently raging, and then allying themselves, however tenuously, to those hopeful winners. We now know that the only thing that ultimately might have worked out for those Indians was to prevent any Europeans from even landing in the New World...but I'm glad they didn't, because then we wouldn't have all of these fabbo American starforts to admire.

Important English persons first started considering building a fort where the Little Tennessee and Tellico Rivers meet in 1708. Colonists in South Carolina traded extensively with the Cherokee, but found the Injuns to be slippery characters (an opinion that was certainly mutual), and it was felt that a permanent projection of power in the region would give them a measure of control over events. Great idea, agreed everybody, but no fort.

|

Fort Loudoun and the remains of Tellico Blockhouse, which once sat across from one another on the Tellico River, now have Tellico Lake to contend with. Water levels rose in the 1970's due to enthusiastic damming on the Little Tennessee River, and the reproduction Fort Loudon that we see today had to be carted a little way uphill to keep it dry. Fort Loudoun and the remains of Tellico Blockhouse, which once sat across from one another on the Tellico River, now have Tellico Lake to contend with. Water levels rose in the 1970's due to enthusiastic damming on the Little Tennessee River, and the reproduction Fort Loudon that we see today had to be carted a little way uphill to keep it dry. |

|

By the 1740's the French were well established along the Mississippi River Valley, which was of concern to the British, colonists and the Cherokee. More talk of a fort at this spot, but still no fort.

The Cherokee were not a united, centrally-governed people. Individual villages cozied up to different bunches of Europeans, which brought increasing numbers of Indians under the French sphere of influence. In 1754 the French and Indian War rumbled into being, and the British finally decided to get serious about fortifying, so as to help disuade the Cherokee from allying with the French: Virginia's Governor Robert Dinwiddie (1692-1770)* was granted funds to build a fort near the confluence of the Little Tennessee and Tellico Rivers. |

|

While Dinwiddie was a friend to all starforts due to his part in initiating a fortification where the Ohio, Allegheny and Monongehela Rivers meet in 1754 (the troop of Virginians he sent on this mission before war was even declared were chased away by the French, who built Fort Duquesne there instead), in this case he thought he knew better than the authorities (or perhaps he considered him self the authority), and used most of the money to help fund the Braddock Expedition, which did not turn out well for anyone who spoke English. The Braddock Expedition had been such a disaster that much of Virginia's frontier was left open to the depredations of whomsoever might choose to depredate. The Cherokee agreed to provide 600 warriors for border defense, if the English would get off of their tuckuses and build that fort they'd been talking about for so long.

|

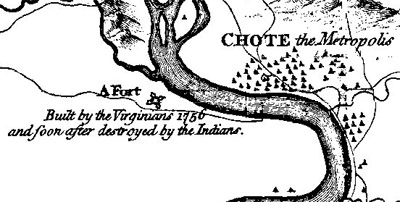

Dinwiddie made plans with South Carolina's governor to work together and make a fort happen. The Virginia contingent of 60 fort-buildin' men arrived at the Cherokee Mother Town of Chota, near the confluence of the Little Tennessee and Tellico Rivers where Fort Loudoun would later be built, on June 28, 1756.

The South Carolina group couldn't get its act together, however, and was still several weeks from arrival. Reasoning that there was no point in hanging around and waiting for the South Carolinians to show up, the Virginians built the appropriately-named Virginia Fort.

|

|

A section of Henry Timberlake's Draught of the Cherokee Country, 1762. Virginia Fort was not a starfort as one might be led to believe from this representation, but a rather undignified square. A section of Henry Timberlake's Draught of the Cherokee Country, 1762. Virginia Fort was not a starfort as one might be led to believe from this representation, but a rather undignified square. |

|

This was a square fort whose walls were earthen embankments topped with a seven-foot-tall wooden palisade, 105 feet long on each side. Surely the watching Indians said, yeah, we could never have figured out how to build this marvel of technology! The Virginians finished their square in August, and having no orders beyond "build a fort," went home...at which time the sarcastic Indians said, swell, you left us an empty square. Our prayers have been answered.

Did the South Carolinians ever make it to Virginia Fort? Apparently not, but what amounted to the South Carolinian contingent of this operation, 80 British troops and 120 provincial soldiers, finally made it to the location of our present interest at the beginning of October 1756...upon which arrival they completely ignored Virginia Fort and started arguing about where and what a new fort should be.

|

Somebody's most excellent dronework. Somebody's most excellent dronework. |

|

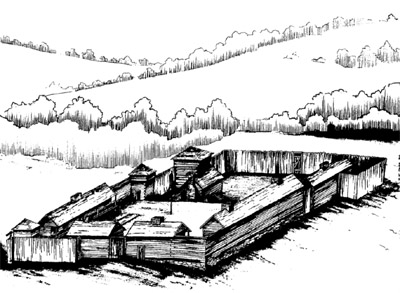

A proper starfort needs cannons, and twelve relatively small guns (300lbs each, which seem small until you need to transport the things) were laboriously dragged over the mountains and through the wilderness for the new fort's armament. Much squabbling about the fort's design and placement eventually resulted in the diamond-shaped, wooden-walled entity we see today, bastions on each corner with risers for three guns each. |

|

These bastions were named after King George II; Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (the present Queen of Britain); the Prince of Wales (whom, confusingly, was the present King George III); and the Duke of Cumberland, who at the time was William Augustus. The whole shebang was surrounded by a three-foot-deep, 10-foot-wide dry moat that was filled with honey locust branches, which have particularly nasty, long thorns in plenty. The fort's main gate was covered by a ravelin, which unfortunately does not figure into the reproduction of Fort Loudoun that we see today. The new fort was completed in May of 1757...but after whom shall it be named? South Carolina's Governor, William Lyttleton (1724-1808) made that challenging decision. And the honor went to...John Campbell, 4th Earl of Loudoun (1705-1782), was not a popular fellow in the thirteen colonies. He had sailed to North America in 1756 as the new Commander-in-Chief and Governor of Virginia, and upon arriving learned that some American merchants were continuing to trade with the French, despite being instructed otherwise: We are at war with the French he reasoned, not unreasonably. Loudoun temporarily closed all American ports to prevent such behavior, which did not endear him to the mercantile Yankees. In August of 1757, Loudoun was off dithering in Canada, trying to figure out how to take the mighty fortifications of Louisbourg from the French (unsuccessfully), when those same French and their Indian allies captured Fort William Henry at the lowest tip of Lake George in New York. Loudoun was replaced and sent home. Despite being generally loathed and of dubious ability, Loudon had not only Loudoun County in Virginia named after him**, but also the starfort of our current interest.

|

Fort Loudoun was reported to be ready for action on May 30, 1757, but work continued into 1758, when its well was completed and some 700 acres of crops were planted: One of the reasons this site was ultimately chosen was ready access to those 700 acres. A garrison had to feed itself after all, and while the Cherokee were willing to provide some food, nobody expected them to wholly provide for the fort's inhabitants: The garrison numbered around 130, with an additional 60 or so wives, "wives," and children.

Perceived insult led to distrust led to whooping and yipping led to scalped settlers led to Cherokee hostages being untidily killed at Fort Prince George, another undignified British square fort in South Carolina, in February of 1760.

|

|

One of those tiny, eminently manageable 300lb guns inside Fort Loudoun today. Might I take this opportunity to say, Tripadvisor: Where to? One of those tiny, eminently manageable 300lb guns inside Fort Loudoun today. Might I take this opportunity to say, Tripadvisor: Where to? |

|

The English and Cherokee were no longer best buddies, and 70 men were sent as reinforcements to Fort Loudoun. The Cherokee were outraged by the killings at Fort Prince George, and attacked our fort on March 20, 1760, led by the mighty Standing Turkey, whose position in his society was First Beloved Man. His name in Cherokee was Conocotocko II***, differentiating him from Conocotocko I, who had been his uncle, Old Hop (the previous holder of the First Beloved Man office).

The Indians fired on Fort Loudoun but were kept at a distance by those guns that had been dragged over the mountains four years previously. Time for a nice, long siege, agreed the Cherokee. Long it was, and by the beginning of August, food was running out and so were members of the fort's garrison. The sad decision was made to surrender the fort on August 8, 1760. The departing garrison was promised safe passage back to Fort Prince George by the Cherokee, who proceeded to attack the British anyway, two days later. Three officers, 23 soldiers and three women were killed before the British surrendered, whereupon they were taken into captivity and mostly ransomed off in South Carolina and Virginia over the next several months.

|

The remains of Tellico Blockhouse, and a drawing of what it probably looked like when it still existed. The remains of Tellico Blockhouse, and a drawing of what it probably looked like when it still existed. |

|

Never ones to forego an opportunity to stick it to the English, the French sent an expedition from Louisiana to take control of Fort Loudoun, but the Tennessee River proved unnavigable and they decided it wasn't worth the trouble it would take to get there. An English expedition made it back in 1762, which included one Henry Timberlake (1735-1765), whose helpful map of the region is included on this page: Timblerlake reported that Fort Loudoun was in ruins at the time of his visit. To many an Indian's dismay, The United States was victorious in its Revolutionary War (1775-1783) and the English, who had supplied those Indians with arms and inspiration, mostly departed and went to Canada or back across the pond: For an accounting of those British troops that did not leave when they were supposed to, check out this site's Starforts of the Jay Treaty page. Indians and settlers squabbled long and hard, and the United States waited until 1794 to make another fortificational attempt at the river confluence of our present interest, which they did to try to slow the tide of settlers from pouring into the area. Tellico Blockhouse, which was built at least partially with materials scavenged from what was left of Fort Loudoun, was completed in 1794 and located across the Tellico River from Fort Loudoun. Settlers interested in doing their settling thing in Cherokee lands were required to have written pass from the blockhouse's commanding officer. |

|

In addition to its intent to keep order in the region and serving as a trading post, Tellico Blockhouse was also home to Tellico Factory. This was an enterprise dedicated to teaching Indians in the modern methods of agriculture and industry, in the hope that they might better integrate with the American society that was coming whether they wanted it or not. This relatively enlightened program came about thanks in no small part to genuine American Founding Father and present US Secretary of War, Henry Knox (1750-1806)****.

|

Knox had been the general in charge of George Washington (1732-1799)'s artillery during the American Revolutionary War, was made Secretary at War in 1785, and then Secretary of War in 1789, when the ridiculous at office was abolished. As regarded the Indian situation, Knox held the outlandish opinion that the Indians possessed the lands they occupied, that the Indian nations were sovereign, and suggested that the federal government was the only body that could deal with them on matters of land redistribution (as opposed to the states or private individuals).

Though Knox was clearly crammed full of good intentions, the situation was beyond his control and both the Cherokee War and Northwest Indian War took place during his time in office. Settlers were gonna settle, or why would they even be called settlers? In 1792, First US Secretary of State and later Third US President Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) stated that the Doctrine of Discovery, a pseudo-legal concept that had fueled much of the righteous land-grabbing behavior of European powers during the Age of Discovery, would be really cool to apply in our case as well! This was solidified by the US Supreme Court in 1823: Discovery of lands previously unknown to Europeans gave the discovering nation title to that land against all other European nations, and this title could be perfected by possession. Indians, who were considered even lower in social stature than Europeans, apparently didn't figure into these interactions at all.

|

|

Genuine US Founding Father Kenry Knox, wearing the lovely honorary starfort that bears his name at an appropriately jaunty angle. Genuine US Founding Father Kenry Knox, wearing the lovely honorary starfort that bears his name at an appropriately jaunty angle. |

|

Tellico Blockhouse did its part in furthering Cherokee-White Person relations, but by 1807 there were hardly any Indians left in the area to come and be positively influenced by the Tellico Factory. The fort's garrison was moved closer to where the Cherokee now were, leaving only a few soldiers at Tellico Blockhouse, just in case an Indian showed up and had some questions about modern agricultural drainage practices. The post was finally abandoned at the end of December 1811.

The Great Depression of the 1930's may have been depressing for humans, but it was a happy time for many of America's forgotten starforts. Looking to meaningfully employ those out-of-work masses before they embraced Communism, the US government initiated the Works Progress Administration in 1935. The WPA ultimately employed 8.5 million Americans up until 1943, when the Second World War (1939-1945) was recognized to be a better use of our masses.

|

Fort Loudoun in the process of being moved in the 1970's. Fort Loudoun in the process of being moved in the 1970's. |

|

But during those golden WPA years, America's infrastructure was strengthened. Roads, bridges, schools and hospitals were built by these happy throngs of federally-employed Americans. State governors determined many of the projects that were undertaken, and historic sites were frequently the targets of governmental largesse. Fortunately, such was the case with Fort Loudoun!

The Fort Loudoun Restoration Project was launched in September of 1935. Excavation proceeded at an unhurried pace over the next three decades, and a reconstruction of Fort Loudoun was completed by the mid-1960's, whereupon it was declared to be a National Historic Landmark.

|

|

And then they had to move the whole thing! Dams along the Little Tennessee River raised the water level, necessitating moving the reproduced Fort Loudoun some 17 feet higher up than the original. By 1977 everything had been safely relocated, and Fort Loudoun State Park was opened that year. What's left of Tellico Blockhouse is also on park grounds.

...and, wouldn'tcha know it, there's another Fort Loudoun.

The Other Fort Loudoun |

At the town of Fort Loudon (modern spelling) in Franklin County, southern Pennsylvania, there is another Fort Loudoun: Named for the same person, built for the same war. Twas built in 1756 as part of the Forbes Expedition, a "protected advance" through the wilds of Pennsylvania with the ultimate aim of removing the French from Fort Duquesne at what is today the city of Pittsburgh. The cool thing about the Forbes Expedition was that in order to protect that advance, the English built a series of forts along the way, with Fort Ligonier being the most notable of the bunch. After the French and Indian War had been concluded with neither the French nor the Indians claiming victory, the English resumed trading with the local Indians, which included arming them. Pennsylvanian settlers felt this to be intolerable, as it would be they who would come up against these armed Indians, and a series of attacks on supplies intended for the Indians took place in March of 1765. Some of the perpetrators of these attacks were captured by the British and imprisoned at Fort Loudoun...which seemed like problem solved, until 300 of the perpetrators' closest friends showed up at the fort, demanding their release. A tense several months followed, concluding with around 100 Pennsylvanians continuously firing on Fort Loudoun on the evening of November 16, 1765. The fort's garrison was low on ammunition and fired exactly one shot in return to the Pennsylvanian fusillade.

|

|

This Fort Loudon's logo is much more impressive than the fort itself. |

|

The next morning, the British agreed to turn over a small number of rifles and smoothbore muskets that had been a point of contention, and departed for Fort Bedford, the next fort up the line towards Pittsburgh. The Pennsylvanians apparently did not garrison Fort Loudoun, which deteriorated into nothingness but was reproduced in 1993 by the Fort Loudoun Historical Society.

*Dinwiddie would go on to have a county in Virginia named after him, and it has a very pretty historic courthouse.

**Loudoun County also has a lovely courthouse. If it's an 'istoric courthouse in Virginia, I got it.

***Conocotocko's name, never intended to be spelled by white persons, has appeared throughout literary history as Canackte, Canacaught, Canacackte, Canacockte, Caneecatee, Cannacaughte, Conarcortuker, Concauchto, Connagatucheo, Connecocartee, Connecorte, Connecortee, Connecote, Connetarke, Connocotte, Connocte, Conocortee, Conocotocho, Conogotocke, Conocotocko, Conogotocho, Conogotocka, Conogotocke, Conogotocko, Conogtoco, Cunigatogae, Cunnacatoque, Cunnicatoque, Guhna-gadoga, Kanagagot, Kanagagota, Kanagataucko, Kanagatoga, Kana-gatoga, Kanagatucko, Kanetekoka, and Kunagadoga. You're welcome!

****Though born in Boston, Knox adopted Maine as his home state. He had a county named after him in Maine (no representative pic, sorry. Write your congressperson and ask that Knox County be moved to Virginia and I'll get right on the pictaking process) in 1860, but much more importantly he had an absolutely gorgeous pentagonal fort built in his name, and that fort is called, you may have already guessed it, Fort Knox.

*****No fewer than 26 states have a Jefferson County. None of those states are Virginia. |

|

|

|

|

|

|