|

Fort Popham

Phippsburg, Maine, USA

|

|

|

Constructed: 1861-1869

Used by: United States

Conflicts in which it participated: None

|

Though unfinished, untested and an un-starfort, Fort Popham stood sentinel on the Kennebec River through four wars, theoretically keeping the shipyards at Bath and Maine's state capital, Augusta, safe from seafaring Confederates, nautical Spaniards and oceangoing Germans in that order.

At the beginning of the 17th century, all of North America's eastern coast, from Spanish Florida to New France in what is now Canada, was known as Virginia. England's King James I (1566-1625) chartered the Virginia Company in 1606, to raise money from investors to settle Virginia.

Within this organization were two competing branches: The Virginia Company of London, which successfully established a colony at Jamestown in 1607; and the Plymouth Company. |

|

|

|

Settlers of the Plymouth Company, 120 colonists led by George Popham (1550-1608), arrived at the mouth of the Kennebec River in August of 1607 and immediately did what all right-thinking colonists did in the era in question: They built a starfort! Fort St. George, named for England's Patron Saint, was built by the colonists on Sabino Head, just across a little bay from Hunniwell Point, where Fort Popham sits today.

|

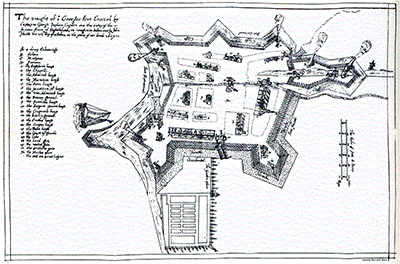

Fort St. George, immediately built by the wise Popham colonists upon their arrival to the New World in August of 1607. |

|

Fort St. George mounted nine guns of various (small) sizes, and contained eighteen buildings. The map to he left, drawn in October of 1608 by colonist John Hunt, somehow found its way into the clutches of Pedro de Zuniga, Spain's ambassador to England. While the Spanish never seriously operated as far north along the American coast as Maine, they were nonetheless extremely interested in what the English were up to, and the layout of their colonial forts.

Hunt's original map was lost, but a copy was found in Spain's National Archives in 1888, thus preserving it for us to look at and be unable to read today. Thanks, Spain!

|

|

|

George Popham was elected President of this new colony, but he died in 1608. Overwhelmed by the harshness of the Maine winter and distressingly leaderless, the rest of the colonists abandoned their starfort the following Spring and returned to England. Though the Popham Colony predated the much-vaunted Plymouth Colony by 13 years, it was ultimately unsuccessful, and thus generally forgotten to history.

Fast forward, if you'd be so kind, to the middle of the 18th century. The town of Bath, up the Kennebec from the ill-fated Fort St. George, established itself as a shipbuilding community in 1743. By the mid-19th century, Bath was the nation's fifth-largest port, along a coast that had been raided at the British Royal Navy's whim during the American Revolution (1775-1783) (at which time a minor gun battery existed on the site of the future Fort Popham) and War of 1812 (1812-1815).

|

|

|

Maine had become a United State in 1820, and the city of Augusta, also up the Kennebec River, was designated it's capital city in 1827...which made two strategically important locations on the Kennebec, not yet protected by a starfort. For heaven's sake Maine, get on it already!!

Fort Popham's majestic backside, as it appeared when I visited in May of 2015. The back of the fort was originally built as a low moated curtain with a central gate, and 20 musket loopholes. It's all still there except for the moat!

Maine, or more precisely the United States government, finally got on it in 1857, by authorizing an actual fortification to be built on Hunnewell's Point. Though it was technically planned and built as part of America's Third System of Seacoast Defense, the design of Fort Popham, as well as that of other forts planned at the time in question, were unique to that system.

|

An aerial view from 1936. Thanks, Fortwiki.com! An aerial view from 1936. Thanks, Fortwiki.com! |

|

During this period, a grand vision of slab-sided monstrosity fortifications, with three masonry tiers of casemated gun emplacements, each belching huge projectiles at foolishly defenseless attacking ships, floated dreamlike in the imaginations of the US War Department. The construction of several such fortifications were initiated in the mid-19th century at some of America's imagined hot spots: Fort Jefferson in the Gulf of Mexico, and reworkings of Fort Constitution and Fort McClary guarding Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in New Hampshire are examples of this phenomenon. Interestingly, precisely zero of these projects were ever completed. |

|

|

It's easy to understand why such fortifications would be desirable. With naval gunnery ever improving, and the added game-changing development of the ironclad warship (the CSS Virginia had wreaked havoc on the US Navy at Hampton Roads in March of 1862), the gentlemen with the impressive facial hair of the federal government felt sure that masonry atop masonry was the only sure way to defend against a belligerent navy in the 1860's.

|

Unfortunately, events early in the US Civil War (1861-1865) demonstrated the deficiencies of masonry fortifications in the modern era. The war opened with the semi-obliteration of Fort Sumter at Charleston, South Carolina; continued with the swift defeat of Fort Pulaski at Savannah, Georgia; then saw the rapid destruction of Fort Macon at Beaufort, North Carolina. Three breathtaking masonry fortifications, whose defenders felt pretty good about themselves and their situation until the bombardments began...and these three were by no means the only previously indestructible forts to fall to the latest weaponry in this conflict.

|

|

Impressed? You should be. Impressed? You should be. |

|

Suddenly all of the massive works in a state of mid-construction along the Union's shores seemed less necessary than they had before the war started. Work was eventually abandoned on Fort Popham, with only the two tiers we see today completed.

But even in a state of 2/3 of its intended size, Fort Popham would have been a sticky wicket indeed for an approaching vessel with ill intent. A closed lunette built with granite blocks, the nonstarfort of our current interest was thirty feet high facing the river, and would have defended the mouth of the Kennebec with 36, ten- and twelve-inch guns in two tiers of vaulted casemates...a daunting obstacle for any ship at the time, but now understood to be vulnerable to the concentrated attentions of rifled artillery.

|

The business end of Fort Popham, from the breakwater afront. The business end of Fort Popham, from the breakwater afront. |

|

After the war, Fort Popham was garrisoned until 1869. Instead of making an effort to come up with the next generation of seacoast defense for the United States, the government collectively said, "Hmmm..." and did what amounted to nothing along these lines for the next thirty years. Most of Fort Popham's guns were dispersed through New England, to martially decorate parks and government buildings.

In light of alarming European advances in gunnery and naval ability, a brief enthusiasm for modernizing the defenses of America's shores took place in the 1870's. Plans were made and some projects were initiated, but anything military was not what a newly re-United States wanted to deal with at the time, so our shores continued to be "defended" by declining, ungarrisoned husks that were "armed" with rusting Rodman Guns and Parrot Rifles. |

|

|

We find ourselves once again thanking the Spanish Empire, this time for ruling Cuba in a heavy-handed fashion! Though a global power due in no small part to the careful maintenance of an overseas empire for several hundred years, by the end of the 19th century the Spanish Empire was heading for rock bottom: Spain was on the wane. A buff young United States had a not-completely-unreasonable desire to reign supreme in it's own hemisphere, and there was Spain, fighting a Cuban independence movement 90 miles south of Florida.

Spain had the international reputation of possessing and wielding a most formidable navy, honed by centuries of colonial domination and paid for by an endless stream of treasure from those colonies. During the period in which the United States was beginning to bump heads with Spain over the latter's possessions in the Caribbean, the Spanish Navy's Numancia was the first ironclad warship to circumnavigate the globe (which took place in the late 1860's), and their Peral was the first electrically-powered, military submarine to take to the seas (1888). The United States could, therefore, be excused for believing that the Spanish Navy was a modern, irresistible juggernaut of nautical force, which would sooner or later come down on America's shores like a steel hurricane, should any sort of hostilities be initiated.

|

The United States' lax attitude of the past 30 years as regarded its seacoast defenses now seemed suicidally silly. In the 1890's a huge effort went into the upgrading of America's fortifications, which became known as the Endicott Period, named for US Secretary of War William Crowninshield Endicott (1826-1900). During this period, many of America's vital strategic interests were violently enhanced with countless tons of concrete and steel, in the form of batteries-a-plenty. Fort Popham was initially granted one temporary gun mount, slightly to the fort's south, upon which an 8", breechloading gun was affixed. That and four old 15" smoothbore Rodman Guns were expected to hold off the Spanish Armada.

|

|

The temporary Endicott Battery outside of Fort Popham. Should you wonder when it was built, just roll over the image with your cursor! The temporary Endicott Battery outside of Fort Popham. Should you wonder when it was built, just roll over the image with your cursor! |

|

Once the Spanish-American War finally came to pass in 1898, the Spanish Navy was revealed to be however the opposite of a modern, irresistible juggernaut of nautical force could be described. Two of Spain's three naval groups were swiftly annihilated by the US Navy and swept from the Caribbean Sea and Pacific Ocean, while the third group raced home to defend Spain's coast from an expected American invasion.

Fortunately Spain had no secret, supermodern nuclear naval group dedicated to the North Atlantic, so Fort Popham spent the war peacefully. The fort was briefly garrisoned, but spent much of the war, indeed most of the Endicott Period, manned by a single Ordnance Sergeant. This is not to say, however, that the federal government had given up on defending the mouth of the Kennebec River.

|

Fort Baldwin, as it sits next to Fort Popham. Fort Baldwin, as it sits next to Fort Popham. |

|

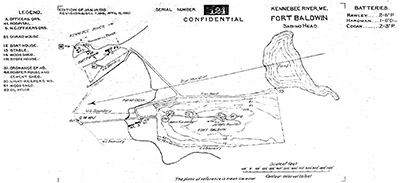

By 1905 the government had bought 45 acres of land on Sabino Head, which included the location of the Popham Expedition's Fort St. George. One of the main principles of fortification in the Endicott Period was that those fortifications should be difficult for an attacker to immediately identify, thus three low-profile batteries were built there by 1908: Battery Cogan, with two 3" pedestal-mounted guns; Battery Hardman, with one 6" Disappearing Gun; and Battery Hawley, with two 6" pedestal-mounted guns.

Weirdly, no quarters or other support structures were built for the men who might notionally operate these guns, so the newly-initiated Fort Baldwin, as this collection of batteries was named, was left in the hands of a single Ordnance Sergeant. Fort Baldwin was named for Colonel Jeduthan Baldwin (1732-1788). |

|

|

Baldwin had been an American military engineer during some very trying times: He fought with the British in the French and Indian War (1754-1763), assisting Captain William Eyre (d.1764) with the construction of Fort William Henry. Lessons learned during this conflict helped Baldwin become Chief Engineer of the Northern Theater Army during the American Revolution (1775-1783), in which post he strengthened the defenses at Fort Ticonderoga. Another war broke out in Europe in 1914, into which the United States leapt in 1917. This was of course the First World War (1914-1918), which brought a merry garrison back to Fort Popham for the last time. Though no longer a source of defensive gunfire, Fort Popham was still an important part of the Endicott Era defensive strategy, in that electrically-fired mines had been liberally sprinkled throughout the entrance to the Kennebec River, and the minefield's Fire Control system was operated from within the old fort. A series of unpleasant-sounding tar-paper-nailed-over-wood-frame buildings were constructed as "shelter" for this garrison of around 200 men, who must have primarily stood around looking at each other, as it couldn't have taken more than a few dudes to operate the minefield controls, and the only semi-modern gun at Fort Popham, the 8" breechloader outside the fort at the 1898 battery, was apparently no longer there by 1916. And surely nobody expected to deflect the Imperial German Navy with 40-year-old Rodman Guns?

|

Perhaps so, because all of Fort Baldwin's 6" guns were shipped off to Europe in 1917, leaving Battery Cogan's two 3" guns as the only modern weaponry defending the mouth of the Kennebec. But ultimately the decision to send Fort Baldwin's guns to Europe proved to be the right one, as Germany was crushed under an enormous pile of gun tubes relocated from America's coastal defenses.

Another war passed by without noticing the Kennebec River. But how long would the Kennebec's luck last?

|

|

The superduper secret plan of Fort Baldwin. Sorry, but as you've seen this, I will now have to kill you. Thanks, Fortwiki.com! The superduper secret plan of Fort Baldwin. Sorry, but as you've seen this, I will now have to kill you. Thanks, Fortwiki.com! |

|

Forever. Forts Popham and Baldwin were sold to the state of Maine in February of 1924 for use as public parks, and Fort Baldwin's remaining gun mounts were transferred to Fort Preble in Portland.

Our fort and faux fort were federalized in 1941 with the United States' joining of the Second World War (1939-1945). A battery of four 155mm guns on Panama Mounts were installed around Battery Hawley at Fort Baldwin, and a five-story Artillery Fire Control Tower was also constructed: This was one of four such towers intended to direct fire from two huge new 16" guns installed 40 miles away at Peak's Island Military Reservation, in Portsmouth Harbor.

|

The Panama Mount was developed by the US Army in Panama in the 1920's. It was a relatively simple method by which to turn a mobile 155mm gun into a solid fixed gun position, and was used to augment older gun positions, often of the Endicott Period. This Panama Mount is at Battery 155 next to Battery Cooper, an Endicott battery at Fort Pickens at Pensacola, Florida. Roll over to see an M1918 155mm gun and it's crew on a Panama Mount, at the mouth of Cape Cod Canal in Massachusetts during the Second World War. The Panama Mount was developed by the US Army in Panama in the 1920's. It was a relatively simple method by which to turn a mobile 155mm gun into a solid fixed gun position, and was used to augment older gun positions, often of the Endicott Period. This Panama Mount is at Battery 155 next to Battery Cooper, an Endicott battery at Fort Pickens at Pensacola, Florida. Roll over to see an M1918 155mm gun and it's crew on a Panama Mount, at the mouth of Cape Cod Canal in Massachusetts during the Second World War. |

|

During the Second World War, Fort Popham was not armed, but used as a motor pool and storage area for Fort Baldwin. As in previous wars, the enemies of the United States were very frightened by an unarmed fort with trucks parked inside, and thus the waters of the Kennebec remained unchurned by foreign propellers.

Fort Popham was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1969, and is today open to the public as Fort Popham National Historic Site from April 15 to October 30.

One of those electrically fired mines, painted in cheery bright colors, has stood next to Fort Popham's gate as a martial decoration for many years: It can be seen at the base of the flagpole to the gate's right in the picture of the fort's rear, further up this page.

|

|

|

In 1995, an officer of the US Army who was tasked with determining the potential lethal status of old military explosives at historic sites raised some concern when he found that there was no record of that particular mine ever having been rendered safe. Children had been playing upon (and throwing rocks at) that mine for many years, and it would have been most disquieting to learn that they might have been atomized in an instant. Several holes were drilled in the mine, and it was determined to be empty, and thus extremely unlikely to explode.

|

|

Fort Popham by Stephen Etnier (1903-1984), painted in 1981. Fort Popham by Stephen Etnier (1903-1984), painted in 1981. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|