|

Fort Sumter

Charleston, South Carolina, USA

|

|

|

Constructed: 1829-1861, 1870-1876, 1898-1899

Used by: USA, CSA

Conflict in which it participated:

US Civil War

|

If ever a non-starfort has earned the right to be considered an honorary starfort, it's Fort Sumter. Built at the tail end of the starfort era, its destruction served not only as the event that sparked the US Civil War, but also the beginning of the end for masonry forts, star- or otherwise, the world over.

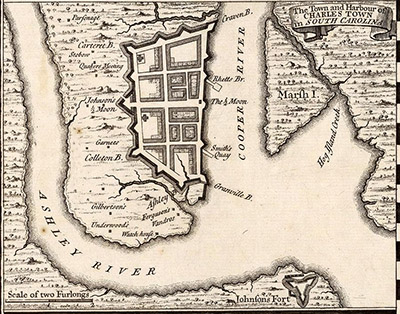

Founded in 1670 and named Charles Town to honor England's King Charles II (1630-1685), the city of Charleston took on its current spelling in 1783, at the conclusion of the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). |

|

|

|

In Charles Town's early days, France and Spain took issue with England's claim to any lands in the region. Pirates and Indians raided ye towne on several occasions (the famed pirate Blackbeard (Edward Teach (1680-1718)) blockaded Charles Towne's harbor for several days in May of 1718). Royal Governor of the province of Carolina, Nathaniel Johnson (1644-1713) designed impressive defenses for Charles Town in 1704.

|

Charles Town's defenses in the 1730's, as depicted by cartographer Herman Moll (1654-1732). Check out that awesome Johnson's Fort at the bottom right!!! Johnson also appears to have had his own "Half Moon" on the left side of the city's main defenses. Charles Town's defenses in the 1730's, as depicted by cartographer Herman Moll (1654-1732). Check out that awesome Johnson's Fort at the bottom right!!! Johnson also appears to have had his own "Half Moon" on the left side of the city's main defenses. |

|

Charles Town developed into a major point of entry into England's southern American colonies, as well as the largest point of entry into America for African slaves. By 1708 the majority of the colony's inhabitants were slaves, which may have had something to do with South Carolina being the first state to secede from the Union in 1860: Nobody had more to lose from the abolition of slavery than the folks who were completely surrounded by slaves! But we're not there yet. The colony of South Carolina declared itself independent from Britain in 1774, and during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) Charlestown was attacked thrice by its previous owners. On the occasion of June 28, 1776, the first iteration of Fort Moultrie, crafted from magical palmetto logs, deflected a British attempt to take Charleston. |

|

During this conflict, Colonel Thomas Sumter (1734-1832) fought on behalf of the soon-to-be United States in South Carolina and Georgia. Nicknamed the "Fighting Gamecock," Sumter led the British on a merry chase during the war, after which he served in the US Congress. A town, counties in four states and the SemiStarfort of Our Current Interest were named after him.

|

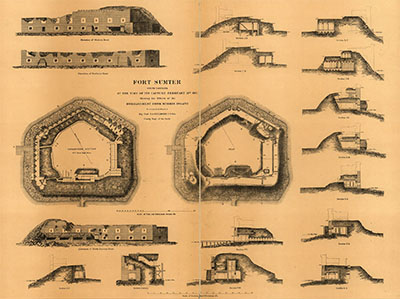

Following the ridiculous War of 1812 (1812-1815), US President James Madison (1751-1836) appointed a Board of Engineers for Fortifications. This body of military and civilian experts travelled up and down the east coast of the United States in the interest of determining which strategic points were the strategicest of all strategic points, and most in need of defense of a starfortical nature. Charleston was identified as one of these strategicological locations early on. I'm pretty sure I gave my proofreader a heart attack with this paragraph. As early as 1805, South Carolina had ceded the land upon which lay Fort Moultrie, Castle Pinckney, Fort Johnson and what would become Fort Sumter to the Federal government, for the express purpose of creating an integrated coastal defense system of Charleston Harbor. The two men in charge of designing this fortification project were none other than American starfort superstars Simon Bernard (1779-1839) and Joseph Totten (1788-1864). The Board of Engineers described that which would be Fort Sumter as, a pentagonal, three-tiered, masonry fort with truncated angles to be built on the shallow shoal extending from James Island. Plans for the fort were drawn up and accepted by the government in 1828, and in 1829 work began in earnest, under the command of Lieutenant Henry Brewerton (1801-1879).

|

A lovely and colorful map detailing Fort Sumter's travails in April of 1861, by Robert Knox Sneden (1832-1918), a landscape artist and cartographer for the Union Army during the Civil War. Click on it, it's considerably larger. A lovely and colorful map detailing Fort Sumter's travails in April of 1861, by Robert Knox Sneden (1832-1918), a landscape artist and cartographer for the Union Army during the Civil War. Click on it, it's considerably larger. |

|

|

It took years to even get the foundation for Fort Sumter built up with tons upon tons of stone, whereupon work was halted in 1834. While South Carolina had ceded the land needed for this Seacoast Federal Program project in 1805, it clearly hadn't ceded the land enough. Increasingly wrapped up in the issue of Nullification, by which South Carolina hoped to "nullify" Federal laws for which it did not care (and which would eventually lead to secession), the government of South Carolina stopped construction of Fort Sumter and questioned the Federal government's authority to use South Carolinian properties for such silliness as building starforts thereupon.

The heroic fortbuilders tapped their feet impatiently as this process dragged on, until finally South Carolina "outright ceded" 125 acres of harbor land to the Federal Government in 1840, and the construction of Fort Sumter resumed in 1841.

|

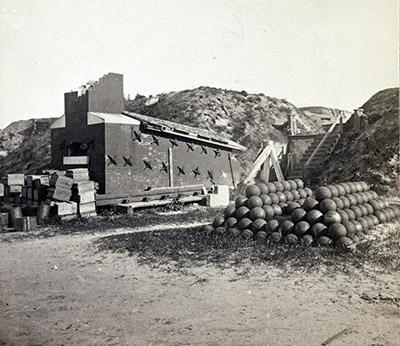

One of Fort Sumter's two hot shot furnaces, in 1865. Thank you, Library of Congress, for having such an awesome online presence!!! One of Fort Sumter's two hot shot furnaces, in 1865. Thank you, Library of Congress, for having such an awesome online presence!!! |

|

Fort Sumter was designed to be manned by a garrison of 650, with 135 guns in three tiers. It had two barracks buildings, an officers' quarters, and two hot shot furnaces. Anyone interested in more detail regarding the construction of Fort Sumter should check out An Overview of the Events at Fort Sumter, 1829-1881 by James N. Ferguson, and presented by the National Park Service. Before any of this could be put into play, however, 300 Africans who had been captured at the mouth of the Congo River with the intent of selling them as slaves in the southern United States, were interned at Fort Sumter for three weeks in September of 1858. The International Slave Trade had been outlawed in 1808, but a healthy "piracy" industry provided plenty o' slaves for those who still wished to purchase them. The ship that carried this particular cargo of slaves, the Echo, was captured by the USS Dolphin off Cuba, and brought to Charleston. |

|

These displeased Africans were held in a Charleston jail for a time, but caused such a sensation (slaves there were in plenty in Charleston already, but the sight of folks directly from Africa, starved and in loincloths, was a rare and delightful occurence in 1858) that they were brought to Fort Sumter, where they were held until the steam frigate USS Niagara picked them up and "returned" them to Liberia. As unhappy as all of this was, it's gratifying to note that someone was at least trying to do the right thing with the Liberia business.

|

The southern folks with an interest in secession from the Union finally found their casus belli in the election of Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) as the 16th President of the United States on November 6, 1860. Lincoln was anti-slavery, did not acknowledge anyone's right to secede, and would not yield Federal property to those who did wish to secede.

In light of such rabidly unreasonable positions in a US President, it's no wonder that South Carolina was the first state to secede from the Union on December 20, 1860. Mississippi, Florida, Alabama, Georgia, Louisiana and Texas joined South Carolina in the first couple months of 1861, and the formerly United States were ready and rarin' for war.

|

|

Fort Sumter as it appeared in April of 1861, at the start of the Civil War. This adorable model is in the fort's museum. Fort Sumter as it appeared in April of 1861, at the start of the Civil War. This adorable model is in the fort's museum. |

|

When these states seceded, many of the Federal forts within their boundaries were garrisoned by single "caretaker" sergeants, who mostly peacefully handed over their charges to the state militias that showed up and demanded surrender (in January of 1861, the Ordnance Sergeant in charge of the Castillo de San Marcos in St. Augustine, Florida, demanded and got a signed receipt for the fort before opening the gates for the Florida militia and walking away, unmolested). The particular exceptions to this phenomenon were Fort Monroe at Hampton Roads, Virginia; Fort Zachary Taylor at Key West, Florida; Fort Pickens at Pensacola, Florida; and Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas off Florida. These heroic starforts would remain in Union hands, and served as burrs in the belly of the Confederacy through the coming Civil War (1861-1865).

|

The sorry state of Fort Sumter upon its eventual recapture by the Union is cataloged in loving detail in this 1865 drawing. Thanks again, Library of Congress! The sorry state of Fort Sumter upon its eventual recapture by the Union is cataloged in loving detail in this 1865 drawing. Thanks again, Library of Congress! |

|

At the moment of South Carolina's secession, Major Robert Anderson (1805-1871) commanded the Federal garrison of Charleston. His little force of 100 (8 of whom were musicians) was stationed at Fort Moultrie on the eastern banks of Charleston Harbor. He knew trouble was coming his way, however, and realized this low-walled starfort, which had successfully defended Charleson from the Royal Navy in 1776 but by 1860 had deteriorated to a state that local cattle frequently if unintentionally blundered into it, would be indefensible under the current state of affairs. Still unfortunately in office, US President James Buchanan (1791-1868) worked until the last moments of his presidency trying not to antagonize the South, and would not reinforce the Charleston garrison. |

|

Anderson moved his men to Fort Sumter under the cover of darkness on December 26, resulting in much patriotic rejoicing in the North, where his actions were viewed as a thumb of the nose to the secessionists. Already living at Fort Sumter were 150 workmen (as the fort was still under construction!), and 45 women and children. Major Anderson dismissed 95 of these workmen as their sympathies lay with the South, and set about determining how to prepare the unfinished Fort Sumter to resist all comers.

Only two of Fort Sumter's intended three tiers of casemates had been completed, and the second-tier casemates had few of their embrasures in place. This of course left great wide openings, which would be perfect holes into which an enemy might gleefully lob things. There were over 60 cannon lying in the fort's parade ground, with only three guns mounted and ready for action...one of which was experimental. In the following four months, Anderson and his little band managed to brick up all those second-tier holes, mount a total of 62 guns, and mine the wharf so as to persuade any attacking ships to dock elsewhere. During this period, however, the Confederacy had not been idle: Batteries had been built all along the coast of Charleston Harbor.

Paranthetically, Abraham Lincoln took office on March 4 of 1861. He made it known that he did intend to send supplies in support of Fort Sumter, which was seen as an act of aggression in the South, and may have been the final deciding factor that led to what came next. And as all American schoolchildren have learned for the past 150 years, what came next was the opening act of the US Civil War.

|

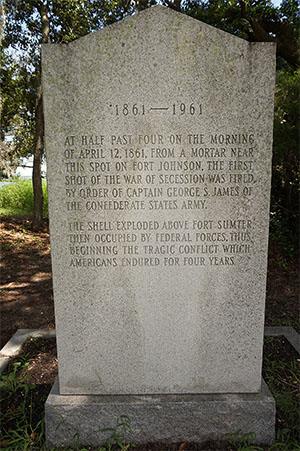

Once the Confederate States of America was officially made an entity in February of 1861, its first priority was to wrest Fort Sumter from the Union. CSA President Jefferson Davis (1808-1889) ordered it so, and in the early morning of April 12, 1861, with US Navy ships hovering impotently nearby, hoping in vain to deliver supplies to Anderson's garrison, every gun that could be dragged to the shore of Charleston Harbor opened fire on Fort Sumter. The first shot, which sent a mortar shell that exploded above Fort Sumter at 4:30am, was fired from Fort Johnson.

The bombardment went on for 34 hours. Major Anderson returned fire from Fort Sumter with 48 guns, but his garrison was critically low on supplies of all sorts (every stick of unnecessary wood in the fort had been burned as firewood by this point), and without any sort of support from the Federal government, it was just a matter of time.

After a full day of bombardment, all wood structures within the fort that had not already been burned by the boys in blue had been incinerated by Confederate heated shot, and everything else was badly damaged. Recognizing the inevitable, Major Anderson surrendered Fort Sumter on April 13, 1861. No soldiers had lost their lives during this furious exchange, but perversely one Union infantryman was killed and another badly wounded when Anderson's departing men attempted to fire a 100-gun salute to the American flag before it was hauled down in surrender.

The US Navy was permitted to pick up Fort Sumter's retreating garrison, and the Confederates along the shore cheered Major Anderson's heroic stand, while simultaneously rowing out to take possession of their new, if slightly used, fort.

General P.G.T. Beauregard (1818-1893) had been the commanding officer of the Confederate forces in Charleston during these momentous moments, and he knew that the US Navy would eventually come back in force. Before chuffing off to take command for the First Battle of Bull Run in Virginia in July of 1861, Beauregard saw to it that Fort Sumter would be repaired and improved.

|

|

The Bombardment of Fort Sumter, 1861, by George Edward Perine (1837-1885). The Bombardment of Fort Sumter, 1861, by George Edward Perine (1837-1885).

A marker erected at Fort Johnson in 1961, commemorating that historic thing that happened there. A marker erected at Fort Johnson in 1961, commemorating that historic thing that happened there. |

|

When the Yankees returned with the intent of recapturing Fort Sumter in April of 1863, there were nearly 100 guns and mortars mounted therein and thereupon and ready for action. A caponniere with two flank howitzers had been added next to the fort's sallyport, and two stone masonry "counterforts" had been built on the exterior of the first level's two powder magazines to futher protect them...which structures seem like untidy, ungainly additions to me, but I recognize that my affection for symmetry and clean lines may not always dovetail with military necessity.

|

An actual photograph of Fort Sumter in August, 1863, after Federal guns had pounded on it for a bit. An actual photograph of Fort Sumter in August, 1863, after Federal guns had pounded on it for a bit.

A drawing depicting what happens when you pile dirt and sand atop a destroyed fort and stick a Confederate flag on top. A drawing depicting what happens when you pile dirt and sand atop a destroyed fort and stick a Confederate flag on top.

Fort Sumter in April of 1865, finally back in the hands of the Union. It's safe enough for some ladies to row out to take a look!

|

|

There is no doubt that Fort Sumter was definitely a strategic location of great importance for anyone who wished to utilize Charleston Harbor as a shipping port. It was however so fraught with historic significance to North and South that one suspects that the effort for its recapture may have taken on greater significance than was warranted. But that's kind of like saying the Beatles' White Album really could have been edited down to a single disc. It is what it is, and history speaks for itself. On April 11, 1862, Confederate-held Fort Pulaski, guarding Savannah, Georgia, was pounded into submission by the Union. This feat was achieved by US artillerists under General Quincy Adams Gillmore (1825-1888), who pummelled this impregnible semistarfort with the very latest and coolest rifled guns, firing from far enough away that the fort's defenders were unable to effectively return fire. In April of 1863, the Union was finally ready to start taking back Fort Sumter. And Charleston too, but that was a secondary consideration. |

|

While Gillmore would be responsible for reducing the many forts and batteries around Charleston Harbor, he would not participate in the first effort to take back Fort Sumter: A US Navy force of nine ironclad warships under Admiral Samuel Francis Du Pont (1803-1865) was tasked with steaming about the harbor in a semi-random fashion and shooting at things, which undertaking was expected to somehow result in Fort Sumter being returned to the Union's possession. This operation began on April 7, 1863.

|

Though the Admiral had serious misgivings about his mission, noting that a large number of troops on land would be necessary to recapture Fort Sumter, his ironclads attacked...and were unable to navigate effectively in the shallow waters. The naval force was caught in a crossfire betwixt Forts Moultrie, Sumter and Wagner, the latter of which was on Morris Island, the nearest landward point to Fort Sumter.

Du Pont was forced to withdraw, with five of his nine ships badly damaged. One of his ironclads, the Keohuk, sank soon thereafter. Adding insult to injury, the Keohuk's guns were later dredged up by the Confederates and mounted at Fort Sumter.

|

|

Admiral Du Pont's attack on Fort Sumter, April 7, 1863, from Harper's Pictoral History of the Civil War. Admiral Du Pont's attack on Fort Sumter, April 7, 1863, from Harper's Pictoral History of the Civil War. |

|

By August 17, 1863, General Gillmore had managed to set up a battery of guns on Morris Island, and proceeded to bombard Fort Sumter. Admiral Du Pont, disgraced by his failure to do the thing he was pretty sure he wouldn't be able to do in April, had been replaced by Admiral John A. Dahlgren (1809-1870). Known as the "Father of American naval ordnance," Dahlgren developed a cast-iron cannon whose manufacturing process made it much stronger, more reliable and more accurate than most others of the day. The Dahlgren Gun was the standard cannon on US Naval vessels through the Civil War.

Two US Navy monitor ironclads joined in the bombardment of Fort Sumter on August 17. Over 1,000 shells were fired on the fort on this day, reducing much of its outward appearance to that of a particularly battered snack cake...but not resulting in its surrender. After a few more days of bombardment, with no return fire having come from Fort Sumter for some time, Gillmore demanded it and Fort Wagner's surrender. When this surrender was not forthcoming, Gillmore petulantly turned his guns on Charleston itself, as though those people had any say in the matter.

Petulant or not, this was at least partially intended to serve as a form of psychological warfare against Fort Sumter's defenders...although since Charleston's black population outnumbered the white folks, it's easy to imagine how unmoved the fort's beleaguered garrison was by this bombardment of the city.

|

The interior of Fort Sumter in 1863, by George S. Cook (1819-1902). Cook captured some of the first combat photographs in history during this campaign. Please don't climb on the shot furnace, gentlemen, or the Park Rangers will escort you off the premises. |

|

For the next couple of months, Gillmore and Dahlgren nibbled away at the defenses of Charleston Harbor. The Confederates abandoned Fort Wagner on Morris Island on September 7th, whereupon Gillmore moved in and renamed it Fort Gregg.

Gillmore and Dahlgren did not get along. They differed in opinion as to how to best recapture Fort Sumter and thus worked toward that goal independently of one another, with disasterous results.

Dahlgren's plan, an amphibious assault on the fort which was undertaken on the night of September 8-9, was unsupported by Gillmore. With no guns left in place, Fort Sumter was little more than an infantry post...but an infantry post of 320 alert defenders. |

|

Dahlgren's attacking force of 500 men were met with grenades, "fireballs" and brickbats, and his assault boats were fired upon by Forts Moultrie and Johnson. The Union lost 100 men in this debacle, with many more captured. General Gillmore provided no cover fire for Dahlgren's attack.

By October of 1863, Gillmore had 22,000 men dug in and waiting for action on Morris Island and two other nearby islands. He reopened the bombardment on October 26, which commenced for 41 days. Though the only thing resembling a "wall" still standing was a section of the fort's northeast wall, Fort Sumter's defenders remained defiantly in place.

|

As the interior of Fort Sumter became a less and less pleasant place to exist, the garrison took to digging tunnels for survival. On December 11, 1863, an accidental explosion in a powder magazine started a fire within the fort, which blazed for several days: A delighted General Gillmore helped by firing hot shot into the inferno. Somehow the garrison survived this as well, and dug back in once the fire was out.

By July of 1864, Gillmore had taken a back seat, and a General Foster was running things on Morris Island. Foster determined that it was time to completely atomize Fort Sumter, and began the most intense bombardment of that fort to date on July 7. Our spunky little fort was at this point little more than a pile of rubble with a few hundred filthy dudes living in tunnels therein, and no amount of bombardment could make it much worse.

|

|

Fort Sumter as seen from Fort Moultrie, April 11 2014. Fort Sumter as seen from Fort Moultrie, April 11 2014. Fort Sumter as seen from Fort Johnson, August 12 2017. Fort Sumter as seen from Fort Johnson, August 12 2017. |

|

Foster seemed personally offended that one of Fort Sumter's walls still stood, despite the Union's best efforts to the contrary. He and Dahlgren hatched a cockamamie scheme to float a raft piled with barrels of gunpowder up against that enraging wall, whose destruction would surely, surely, convince the entire Confederacy to surrender forthwith. Unsurprisingly, the tidal currents of Charleston Harbor did not cooperate with this devious plan, and the raft exploded harmlessly out in the harbor.

|

Fort Sumter in 1901. Pretty lighthouse! Fort Sumter in 1901. Pretty lighthouse! |

|

Ultimately, the Union was unable to actively dislodge Fort Sumter's Confederate defenders. General William Tecumseh Sherman (1820-1891)'s fabled March to the Sea through the Carolinas and Georgia forced the men in grey to abandon Charleston, and with it Fort Sumter, in February of 1865.

The men in blue finally paddled over to Fort Sumter, took possession of what must have been their particularly malordorous prize, and cleared out the parade ground. On April 12, 1865, the fort's original US garrison flag was raised over Fort Sumter, with none other than General Robert Anderson, the Union officer who had surrendered the fort to the Confederates in 1861, in attendance. |

|

Little more was done with Fort Sumter for the next few years, other than studying the effects of storms and flooding which were, amazingly, found to be detrimental to the fort's shattered remains. Fort Sumter was still considered a strategically important piece of Charleston Harbor's defense from potential naval adversaries, but all of Charleston was such a mess during the Reconstruction period that plans for Fort Sumter's resurrection were made, but none were acted upon until January of 1870.

And who would be in charge of the effort to restore Fort Sumter to a state of military usefulness? None other than the guy charged with doing the exact opposite for the last few years of the Civil War: Good ole General Gillmore.

|

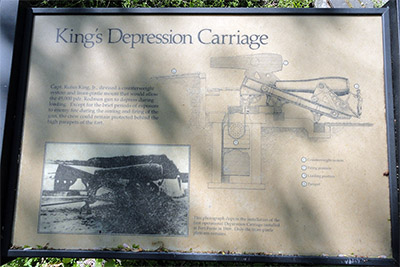

Instead of devoting huge sums of money to the complete reconstruction of Fort Sumter, the plan was to mount thirteen guns en barbette atop the fort's rubble. While this sounds dangerously ill-conceived, the army did spend four years strengthening those walls that were left standing, and generally preparing the fort to be able to support these guns without them immediately tipping over and squashing those people trying to defend the fort. The guns initially considered for this scheme were 15-inch Rodmans mounted on King's Depression Carriages, an early forerunner to those disappearing carriages that would arm many of America's Endicott Period batteries in the 1890's and beyond. |

|

A sign detailing the ill-fated King's Depressing Carriage at Fort Foote on the Potomac River just north of Fort Washington. The first operational King's Depression Carriage was installed at Fort Foote in 1869. Pic taken in April of 2012. You're welcome. A sign detailing the ill-fated King's Depressing Carriage at Fort Foote on the Potomac River just north of Fort Washington. The first operational King's Depression Carriage was installed at Fort Foote in 1869. Pic taken in April of 2012. You're welcome. |

|

Intended to lower the gun after firing, where it could then be reloaded without exposing its gun crew to return fire, these carriages worked much better for breechloading cannon than muzzleloaders...and the US arsenal was popping at the seams with muzzleloading Rodman Guns (over 1800 had been manufactured during the Civil War, and few had been used in action). The King's Depressing Carriage was not adopted by the US military, and not installed at Fort Sumter.

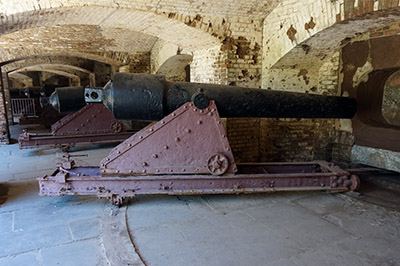

By 1875 Fort Sumter had at least the exterior appearance of a fort. Many of the fort's casemates had been excavated and put to use as housing, storage and magazines, and several new cisterns and a "navigation beacon" were in place. A scarp wall ran all the way around the fort, which mounted thirteen 100-pounder Parrott Rifles in casemates, nine mortars and four Gatling Guns, the latter intended to thwart amphibious landings. Fort Sumter was declared "Good Enough" on April 9, 1876, and all construction ceased.

|

100-pounder Parrott Rifles in some of Fort Sumter's excavated casemates. You don't see those iron carriages still in place very often! 100-pounder Parrott Rifles in some of Fort Sumter's excavated casemates. You don't see those iron carriages still in place very often! |

|

And Fort Sumter was abandoned. From 1876 until 1897, Fort Sumter served as an unmanned lighthouse station. "Good thing we poured all of that money and effort into that fort," agreed everyone proudly.

This abandonment was by no means unusual. America was fed up with all things military after the end of the Civil War...which technically ended in 1865, but which in at least one sense lasted until 1870, when all of those states that had rebelled were readmitted to the Union. South Carolina was readmitted on July 9, 1868. Several fortification efforts intended to address America's coastal vulnerablilites following the war were abandoned in the 1870's. |

|

Thank goodness for America's completely ill-placed fears of the Empire of Spain at the end of the 19th century! Preparation for a defense against the imagined unstoppable juggernaut of Spain breathed new life into America's seacoast fortifications in 1898, and Fort Sumter in particular was in desperate need of resurrection.

An ordnance sergeant, lighthouse keeper and their families had been living in two wooden houses built atop Fort Sumter's earthen berms since the 1870's, and the fort had gone to rot. Its once-fearsome guns had rusted in place, meaning that even if the Spanish had cooperated fully and only approached from directly in front of those guns, it was unlikely that they would prove much of a hindrance to an attacker.

|

The US Army's latest coastal defense guns were 100,000-pound steel monsters that could not be supported by the brick and masonry structures of the early 19th century, thus new batteries would be built atop, within and next to many of America's starforts to mount them.

An enormous concrete battery was "floated" atop Fort Sumter's parade ground, with a complex web of steel beams reinforcing it from below in the sand and loam soil.

|

|

Fort Sumter, during the First World War (1914-1918). Fort Sumter, during the First World War (1914-1918). |

|

This frighteningly hideous battery was named for Isaac Huger (1743-1797), a Charleston resident who served (without, it seems, demonstrable success) as a Brigadier General in the Continental Army during the American Revolution. Mounted atop this battery were two 12" guns, one disappearing and one, weirdly, mounted on a barbette pintle? Why two different mounting styles right next to each other? Must have made sense to somebody at the time.

|

Battery Huger today, with the four flags flown over Fort Sumter during the Civil War: The Garrison Flag, a 33-star US flag; the First National, the first flag of the Confederacy; the Second National, which replaced the first in 1863; and the 35-star US flag, raised over Fort Sumter in 1865. Battery Huger today, with the four flags flown over Fort Sumter during the Civil War: The Garrison Flag, a 33-star US flag; the First National, the first flag of the Confederacy; the Second National, which replaced the first in 1863; and the 35-star US flag, raised over Fort Sumter in 1865. |

|

Something else that made sense to the engineers building Battery Huger (pronounced yoodgie) was a complete disregard for casemates. The area in front of the new battery was filled, so as to better absorb an attacker's fire. This process entombed the Parrott Rifles along Fort Sumter's northeast face...but who cared about the fate of some dumb old Parrot Rifles in the technologically advanced 1890's?! Nobody, but that was a good thing, in that it led to their excavation in place in the 1950's.

Unfortunately, the Spanish-American War ended in August of 1898, mere months after the construction of Battery Huger had begun. Courtesy of the US Navy, two of Spain's three mighty naval fleets lay in untidy heaps at the bottom of various bodies of water, and the feared Spanish Empire had collapsed. |

|

Under normal circumstances this would have been an excellent excuse for the United States to immmediately abandon all war-related fortification efforts, but in this case, the 80-ish Endicott Era batteries planned on the seacoasts of America were completed, despite the unclear and unpresent danger from Spain...but Spain wasn't the only maritime nation whose modern ships were worrisome to the United States at the end of the 19th century.

Work on Battery Huger was officially completed on December 31, 1899. Its two enormous guns sat there until the Second World War (1939-1945), when in 1943 they were removed and replaced by four 90mm, rapid-fire guns intended to neutralize Japanese torpedo boats, should any appear in Charleston Harbor. None did, and this AMTB Battery (Anti Motor Topedo Boat)(differentiating it from ASGFB (Anti Sail Greek Fire Boat)) was deactivated in 1946.

|

The US Department of War handed Fort Sumter over to the National Park Service in 1948. Public tours of the fort were immediately popular, and in August of 1951 an excavation effort got underway.

The decision was made to remove everything that didn't pertain to Fort Sumter's Civil War appearance (except for Battery Huger, because who wanted to wrestle that thing off the island?), so short work was made of the vast majority of General Gillmore's 1870's reconstruction. Plenty of satisfying artifacts were discovered when the parade ground to the west of Batter Huger was cleared down to its original level, including a few Parrot Rifles in relatively good condition.

|

|

What's left of Fort Sumter's parade ground, from Battery Huger. On the right is a 1932 monument presenting the names of Fort Sumter's Union defenders in 1861. What's left of Fort Sumter's parade ground, from Battery Huger. On the right is a 1932 monument presenting the names of Fort Sumter's Union defenders in 1861. |

|

The struggle for Fort Sumter was one of the most significant of the Civil War. Not in a strategic sense, in that nothing war-winningly important hinged on the control of Charleston Harbor. However, many eyes were fixed on this particular part of the conflict for a period of years, all of them determined to either retain or recapture Fort Sumter...and there seemed to be no option of "well, let's just let them keep it for goodness' sake, we'll get it back sooner or later" for the North. Just about every mode of warfare available to American forces were used in the attempt to reclaim or defend Fort Sumter: Artillery barrage; Psychological warfare (in General Gillmore's shelling of Charleston); Amphibious operations; Naval warfare of ironclads and one of the world's first military uses of a submarine (The HL Hunley, a ridiculously unsafe Confederate submarine (which ultimately killed more its own crewmen than Union sailors), sank the USS Housatonic in Charleston Harbor in February of 1863)...and somebody more alert than myself could probably think of at least a few more. Today, Fort Sumter National Monument is one of the nation's most visited parks: Nearly 800,000 folks visited the fort in 2010. I was one of those folks in 2017! Check out Starforts.com's Fort Sumter Visited page if you are somehow not completely overwhelmed with Fort Sumter information by this point! |

|

|

|

|

|

|