|

The Three* Systems of

American Seacoast Defense

*Actually four. Or five, if you wanna get really picky. |

|

|

|

|

When the United States burst forth as a new nation at the end of the 18th century, Great Britain, France and Spain had already been busily building starforts on its shores for three hundred years: The French and Spanish along the southwest and Gulf coasts, and France and Great Britain all over the northeast, along the coast and around the Great Lakes and their attendant rivers.

Notable American Starforts of the Pre-Revolutionary Era

- Fort Caroline

France, 1564: Jacksonville, Florida

- Fort Crown Point

France, 1734: Crown Point, NY

- Fort Frederick

Great Britain, 1756: Big Pool, MD

- Fort Independence (Fort William)

Great Britain, 1703: Boston, MA

- Fort King George

Great Britain, 1721: Darien, Georgia

- Fort Niagara

France, 1725: Youngstown, NY

- Fort Ontario

Great Britain, 1755: Oswego, NY

- Castillo de San Marcos

Spain, 1696: St. Augustine, Florida

- Fort Stanwix

Great Britain, 1762: Rome, NY

- Fort Ticonderoga (Fort Carillon)

France, 1757: Ticonderoga, NY

- Fort William Henry

Great Britain, 1755: Lake George, NY

|

|

Once the US had won independence from Great Britain, however, those in charge of things had to come up with a way to defend itself from those European powers that had been doing their best to gobble up the New World.

Initially, it was hoped that America could exist with a teeny federal army, bolstered by state militias, and that Europe would leave the US to entertain itself while all those ancient monarchies went about their daily business of trying to consume one another.

But the events brought on by the French Revolution (1789-1799) were particularly vicious, and the United States swiftly found itself unable to safely sail the seas, with the British and French navies dashing about, boarding vessels and confiscating American sailors at their whim. Surely it was just a matter of time before every European power swooped down upon a relatively undefended United States, burned everything and demanded fealty to their monarch.

The fortifications used against Great Britain during the American Revolutionary War were pre-existing British or French forts, plus a variety of locally-produced earthworks and batteries. These proved sufficient to the job, but they were a ramshackle collection of frantic efforts, and would not serve to protect a whole nation. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Though he came into office on a platform of vastly cutting federal spending, US President Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) quickly realized how ridiculous such a concept as frugality was, and set the expensive fortification wheel in motion in 1802.

The US Army Corps of Engineers was founded in 1802, and set up what was, until the middle of the 19th century, the only engineering school in the United States, at West Point, New York. Engineers are of course what a nation needs to design and build its own starforts, but when Jefferson waved his hand and commanded that 21 strategic points along America's coast be fortified, the US had no such engineers.

Fortunately, France was practically bursting with engineers, of whom several had served with the Continental Army during the American Revolution. Stephen Rochefontaine (1755-1814) and Louis de Tousard (1749-1817) were two such examples, both of whom toiled to build fortifications for the United States in New England during this period.

Some lasting forts were duly constructed under the First System, but as would become the standard American fortification experience, without the appearance of a clear and imminent threat, everyone (Congress) lost interest in the project, and monies for starforts dried up.

Most of the fortifications built in this period were wood and earthworks, which had deteriorated into uselessness by the time they were needed to defend America's shores during the War of 1812 (1812-1815). |

|

Notable American Starforts of the First System

|

|

|

|

|

America's Second System of seacoast fortification only really differs from the First in that qualified US engineers were finally being produced by the US Army Corps of Engineers, so an effort was made to make the US fortifications system a "home grown" affair. Tensions with France had convinced the US government that it might not be a fabulous idea to depend solely on engineers from foreign lands.

Notable American Starforts of the Second System

|

|

The dividing line betwixt the First and Second Systems is squishy at best: In fact there is no actual "line," as the Systems are more about differing ideas as to whom should design said starforts. As such, coming up with a list of First vs. Second System forts is difficult. Yet you will note that this has not prevented me from doing so anyway. Many forts can be said to belong to more than one System: Forts such as Fort Washington, Fort Adams and Fort Trumbull all had iterations constructed, and then upgraded, in each of the System periods. Confused yet? Good. |

|

|

|

|

The War of 1812 was a particularly terrible idea for the United States. War may or may not ever be the wisest course to follow, but in this case, America's declaration of war against Great Britain seems just plain dumb. Everything certainly did not go Britain's way in the conflict ( Fort McHenry's defense of Baltimore (September, 1814), the Battle for New Orleans (January 1815)), though most of it did (everything else). Exposed for all to see, however, was the United States' complete inability to protect its capital city from a foreign army. On August 24, 1814, Washington, DC was put to the torch by a British army that had relaxingly sailed up the Potomac River with virtually nothing available to even attempt to prevent this from occurring. This war, however ill-considered by a nation with little other than deteriorating, half-hearted fortifications to defend it, was a great war for starforts. Not only was the seminal event of this war (at least in the minds of most Americans) the heroic defense of Baltimore by Fort McHenry and the subsequent composition of America's national anthem, The Star-Spangled Banner, but even the densest American lawmaker, once the conflict was over, understood the desperate need for lots and lots of starforts. |

|

|

|

|

|

Following that ridiculous War of 1812, US President James Madison (1751-1836) determined that the United States would not allow itself to be so babe-in-the-woods vulnerable ever again. He appointed a Board of Engineers for Fortifications, which busily darted about, determining how to spend the $800,000 that Congress had newly appropriated for seacoast defense.

The Board's first report in 1821 listed 50 sites in immediate need of fortification, and by 1850 that number had soared to 200. The US Army eventually built forts at 42 of these sites, with a scattering of batteries and those silly Martello Tower things protecting sites deemed less strategically important. Interestingly, despite the previously-stated desire to make starfort design and construction an all-American effort, two of the names that dominate the early period of the Third System are Frenchmen Pierre L'Enfant (1754-1825) and Simon Bernard (1779-1839). L'Enfant not only designed both Fort Delaware and Fort Washington, but is also responsible for the city layout of post-burned-by-the-British Washington, DC; while Bernard was simply all over the place. By my count, Simon Bernard is responsible for the design of at least TEN Third System starforts, including such ridiculously important examples as Fort Monroe, Fort Adams and Fort Pulaski. One might even go so far as to nominate Bernard as the MVP of the Third System of American Seacoast Defense. Another Third System star was Joseph Totten (1788-1864), who studied Bernard's works and took over construction of two of his projects: Fort Adams and Fort Montgomery. Totten was possibly America's first, first-class military engineer, going on to serve as Chief Engineer of the US Army from 1838 until his death in 1864. Sadly, there were no starforts named for L'Enfant, Bernard or Totten: The only thing Totten had named after him was one of the many earthwork forts that protected Washington, DC during the US Civil War (1861-1865). Today, it's a trash-sprinkled, overgrown series of indistinct mounds in a crappy neighborhood. Several of the starforts of the Third System took decades to complete, which is as much a testament to their complexity as it is to the on-again, off-again nature of public interest in such works. |

|

Notable American Starforts of the Third System

- Fort Adams

1857: Newport, Rhode Island

- Fort Clinch

1867: Amelia Island, Florida

- Fort Delaware

1859: Pea Patch Island, Delaware

- Fort Point

1861: San Francisco, California

- Fort Jackson

1832: Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana

- Fort Jefferson

1874: Dry Tortugas, Florida

- Fort Macon

1834: Beaufort, North Carolina

- Fort Macomb

1822: New Orleans, Louisiana

- Fort Monroe

1834: Hampton Roads, Virginia

- Fort Montgomery

1871: Rouses Point, New York

- Fort Morgan

1834: Mobile, Alabama

- Fort Pickens

1834: Pensacola, Florida

- Fort Pike

1826: New Orleans, Louisiana

- Fort Pulaski

1847: Savannah, Georgia

- Fort Schuyler

1856: Throggs Neck, New York

- Fort Washington

1824: Prince George County, Maryland

- Fort Wayne

1851: Detroit, Michigan

- Fort Zachary Taylor

1866: Key West, Florida

|

|

|

|

If the War of 1812 was the inspiration for the start of the starfort's American renaissance, then the US Civil War was the end, in a puff of brick dust. The war started with the destruction of a masonry fort of the Third System, when the federal garrison at Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina was pounded into submission by the massed artillery of the Confederacy on April 13, 1861. At the start of the war, virtually all of the starforts in the southern states were manned with one or two federal caretakers, which allowed local militias to take control of them in January of 1861: One notable exception was Fort Monroe at Hampton Roads, Virginia, which remained solidly in Federal hands throughout the war, serving as an impregnable bastion of Northernness in the south.

Notable Starforts of the US Civil War

|

|

Once the federal government got its act together, it began deploying new, rifled cannon with a level of range and accuracy that was unimagined when America's Third System starforts had been designed. Confederate-held Fort Macon in North Carolina and, more famously, Fort Pulaski in Georgia were blasted to the point of surrender in disturbingly brief periods of time. Third System fortifications already under construction at the start of the war were completed, but no new masonry fort projects were begun. |

Due to the relatively fast-moving nature of the war, virtually all of the fortifications built from 1861 to 1865 were wood-revetted earthworks of varying degrees of complexity. Fort Negley and Fort Union certainly turned out in a properly starfortish manner, but the major fortification efforts, such as those surrounding Washington, DC and the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia and its approaches along the James River, the trenches of Petersburg and the defense of Atlanta, Georgia (where there was, for a brief and stellar moment, such an entity as a Shoupade), primarily involved digging holes and making piles of dirt. Many of those piles of dirt were star-shaped. The starfort concept was still considered the most sensible configuration for a fort that would stand against infantry and relatively small cannon, and Richmond and Washington, DC were surrounded by darling little starfortlets. Very little of these fortifications exist today, sadly, except as indistinct grassy mounds. |

|

|

|

But the rest of the world was watching. France had already been conducting experiments with modern cannon against masonry forts. Guns were getting bigger and more accurate, both on land and mounted on the ships of Europe's increasingly heavily-armored and steam-powered navies.

Following the US Civil War, there were brief periods of interest in upgrading America's shore defenses in the light of the vast improvements in the military arts being made in Europe, but a public weary of war (and the ever-fickle US Congress) just couldn't work up enough enthusiasm to see anything through. By the mid-1870's, a number of such projects had been completely abandoned. |

|

|

Battery Mount Vernon, Fort Hunt, Virginia Battery Mount Vernon, Fort Hunt, Virginia

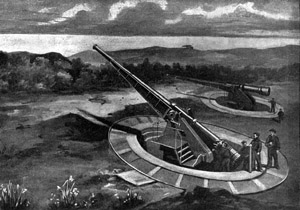

A fanciful depiction of "Our Defence Guns," 1898 A fanciful depiction of "Our Defence Guns," 1898

Fort Howard, Baltimore, Maryland Fort Howard, Baltimore, Maryland

Fort Delaware Fort Delaware

|

|

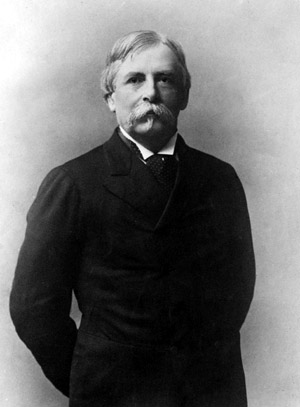

William Crowninshield Endicott (1826-1900) was the Secretary of War for the Grover Cleveland (1837-1908) administration. In 1885 President Cleveland initiated the Board of Fortifications, headed by Secretary Endicott, which included representatives of the army, navy and civilian population. The Endicott Board, as it came to be known, took a good hard squint at America's defenses and determined that they would be unable to deter a semi-determined group of fluffy kittens from landing troops on the shores of the United States.

The fortifications of the Endicott Era came not in the form of forts, but individual batteries. These batteries were frequently built to mount enormous Disappearing Guns, which, when fired, would drop down behind concrete walls fronted by earthen slopes, be reloaded and hydraulically raised to fire again. This would make them difficult to target by the ships that would notionally be trying to get past these batteries. Huge 12" mortars and electrically-fired mines (along with rapid-firing guns to protect the minefields) were also important armaments of these batteries. And there were so many batteries! Around 80 locations benefited from the largesse of the Endicott Board: Fort Washington along the Potomac River alone had an additional seven batteries built in its vicinity during this period, with even more being built across the river in Virginia. |

|

William Crowninshield Endicott: Thank you for your tireless efforts, Mr. Secretary. |

Much of the impetus for this vast fortification program was due to increasing tensions with Spain, whose mighty Armada was imagined to be massed just beyond America's shores, waiting for the moment to pounce. As it turned out, those aforementioned fluffy kittens could have easily defeated the Spanish Navy of 1898, but that wasn't made apparent until the Spanish-American War (1898). Starforts actually fared quite well in this period. The strategic locations at which they had been sited in the 1810's were the same locations that needed to be defensively enhanced in the 1890's, so these new batteries were often built alongside existing starforts, re-emphasizing their importance in the defense of America. In some cases, the beautiful masonry of these starforts was cruelly besmirched by millions of tons of concrete (see Fort Delaware), necessary when these huge new guns needed to be mounted on a starfort, as the original brick structures couldn't support such monstrous weapons.

|

|

By the First World War (1914-1918), most of these batteries' gun tubes had been shipped to Europe, and few were ever returned. It became evident to everyone paying attention to such things that stationary batteries were no longer able to properly defend much of anything, in the age of the aeroplane. By the time of the Second World War (1939-1945), anti-aircraft guns had been placed in and around many starforts and their Endicott Era batteries, but the final iteration of the United States' Seacoast Defense System was now in play.

Boeing's iconic B-17 bomber is famously known as the Flying Fortress. Most assume this is because of the bomber's unprecedented defensive capabilities, but in fact the name came about because it was originally imagined as a flying coastal defense fort. Able to intercept enemy ships at a safe distance from America's shores, the B-17 was intended to be a way to extend the range of the coastal defense of the United States.

|

|

|

|