|

Fort Richmond

and

Fort Tompkins

Staten Island, New York, USA

|

|

|

Constructed: 1847-1861

Also known as: Fort Wadsworth,

Battery Weed

Used by: United States of America

Conflicts in which it participated:

None

|

I'm fairly certain we can all agree with the statement that, New York City is a pretty big deal. As much as residents of Boston, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, Atlanta, Washington DC and Dubuque might passionately argue otherwise, New York is, and pretty much always has been, America's First City.

Florentine explorer Giovanni Verrazzano (1485-1528) is the first European to have sailed into what is today New York Harbor, which he did in 1524. Verrazzano claimed the entire area for France, and named it Nouvelle Angoulême, as it is still known today, by which I mean nobody calls it that anymore.

|

|

New York City positively bristled with fortification in the mid-19th century! Not all of these designated forts still exist today, but this serves to give one an idea of how hard a nut New York would have been to crack for a foe with an intent to invade by sea. |

|

Verrazzano is also remembered as the first European to sail Narraganset Bay at what is today Newport, Rhode Island, home of Fort Adams... and his name will crop up again later in the history of this page's forts. Spain and England also "discovered" New York over the next hundred years or so, mapping and naming various aspects of the region...but the first permanent European settlement there was undertaken by the Dutch.

|

New Amsterdam, starring Fort Amsterdam, as it was in 1660. This is a 1912 redraft of the famous Castello Plan, which dates back to when there actually was a New Amsterdam. Impressed? You should be. New Amsterdam, starring Fort Amsterdam, as it was in 1660. This is a 1912 redraft of the famous Castello Plan, which dates back to when there actually was a New Amsterdam. Impressed? You should be. |

|

This was accomplished at the southern extent of the island of Manhattan, beginning in 1624. Any European power worth its salt knew that erecting a starfort was priority nummer één when colonizin', and the colony of New Netherland grew around the town of New Amsterdam which grew around Fort Amsterdam. In October of 1683, the first session of what would become the New York Legislature was held at Fort Amsterdam: New York City started life as a starfort!

Ownership of the fort and city passed back and forth betwixt the Dutch and the English four or five times until the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) banished European powers from North America for good and all, unless you consider Canada to be part of North America. |

|

Fort Amsterdam, which had been maintained for around 160 years (and which by this point was naturally named Fort George, as the British had been its most recent inhabitants: Over the course of its existence, the fort was also known as Fort James, Fort Willem Hendrik, Fort William Henry and Fort Anne), was recognized as a symbol of colonial oppression and torn down in 1790.

|

Symbol of oppression or not, some folks may have regretted doing away with a perfectly good starfort when events led the young United States back to war with Great Britain in 1812. Just two blocks from where Fort Amsterdam had stood, ground was broken for West Battery, which would become known as Castle Clinton, in 1808.

This round little non-starfort was only operational until 1815, after which it was turned over to the city for use as a theater/beer garden/opera house/etcetera. In 1855 it became an Emigrant Landing Depot, where shady foreigners could be held and scrutinized until they were determined to be safe for emigration, or the people scrutinizing them just got bored.

|

|

That squatty thing at bottom left is Castle Clinton, watching over New York Harbor in a non-military fashion around 1890. In the distance is the Statue of Liberty, which as we all know is perched atop Fort Wood. Thanks for the image, Library of Congress! That squatty thing at bottom left is Castle Clinton, watching over New York Harbor in a non-military fashion around 1890. In the distance is the Statue of Liberty, which as we all know is perched atop Fort Wood. Thanks for the image, Library of Congress! |

|

But you may have noted that the names at the top of this page are Fort Richmond and Fort Tompkins, so let's stop digressing into the 750 other forts in and around New York City, all of which are interesting and worthy of our attention, just not right now thank you.

In 1636, a blockhouse was built on Signal Hill, an elevation on Staten Island which overlooks the narrows that lead into New York Harbor. This blockhouse was constructed by Captain David Pieterszoon de Vries (1593-1655), a Dutch "navigator" (which I suppose is another word for "explorer"). Fort Pieterszoon, as I wish it were named but sadly it was not, lasted until 1655, when it was burnt by Indians of the Susquehannock Nation as part of the Peach Tree War. The Dutch had recently done away with New Sweden, a colony in the Wilmington, Delaware area...and the Susquehannock preferred Swedes to Dutchmen.

The Dutch built another blockhouse on this spot (spoiler alert: We're talking about the future location of Fort Tompkins!) in 1663, but were unable to mount an adequate defense of their colony when the English came a-calling the following year, and New Amsterdam became New York. And then it became New Orange in 1673 when the Dutch took it back, but then it was New York again when the English regained the colony in 1674. |

This 1815 print by Thomas Birch (1779-1851) shows Fort Tompkins on the left (a collection of buildings and maybe a battery?) and what looks like a blockhouse on the right, but is identified as a "small lighthouse." Thanks again, LoC! This 1815 print by Thomas Birch (1779-1851) shows Fort Tompkins on the left (a collection of buildings and maybe a battery?) and what looks like a blockhouse on the right, but is identified as a "small lighthouse." Thanks again, LoC! |

|

That second Dutch blockhouse was the nucleus of at least three future fortifications: A "patriot redoubt" by the name of Flagstaff Fort was thrown up there in June of 1776 to defend New York from the British, who immediately captured it a month later.

Over the course of the next few years the British appear to have developed the site into a full-fledged starfort! In 1782 Flagstaff Fort was described as having five bastions with several barbette batteries: Sounds like a starfort to me! After all that hard work, the British abandoned Flagstaff Fort, along with (almost) the rest of America, in 1783. The 1663 blockhouse remained in place, though what actual function it served cannot be surmised.

|

|

In 1806, the government of New York finally got serious about defending itself, and four new forts were built to defend the Narrows. One was Fort Tompkins, named for Daniel D. Tompkins (1774-1825), who served as New York's Governor from 1807 to 1825. This first version of Fort Tompkins, a pentagon with round bastions on its seaward-facing corners, was made of red sandstone and enclosed the 1663 Dutch blockhouse (we're still keeping that blockhouse around??!). On the waterline down the hill from Tompkins was built Fort Richmond, named for the county in which Staten Island resides (which is named Richmond), also of red sandstone. Fort Hudson and Fort Morton were also built at this time. Four forts, with a grand total of 164 guns! All of these forts were declared fit for use by 1808, even though they were unfinished...and by the end of the War of 1812 (1812-1815) they probably really were finished, and boasted around 900 guns! A seacoast fortification must be able to do two things: Prevent a seaborne enemy from passing unmolested, and defend itself from direct attack on its landward side. Topographical considerations sometimes make the perfect fort difficult to achieve, however. Fort Richmond on the waterline and Fort Tompkins on the high ground were each intended to fulfill one of those roles, while mutually supporting each other.

...and what were Forts Hudson and Morton for? Hard to say. Fort Morton in particular wasn't around for all that long, and little information about either of them seems to remain. One important distinction is that all of these forts were built during the period of the United States' Second System of seacoast fortification, but they weren't part of that system, which was Federal, and the forts of our current interest, at least at this point, were local efforts. 1837 saw Forts Richmond and Tompkins to have deteriorated to a state unfit for defending much of anything, but in stepped the federal government, who initiated a ten year process of purchasing them. |

|

Forts Richmond and Tompkins by Seth Eastman (1808-1875), 1870. Forts Richmond and Tompkins by Seth Eastman (1808-1875), 1870. |

Because the United States had seen the error of its ways (having one's capital city burned to the ground tends to enhance one's clarity), and was now ready to fortify its ever-expanding coastline from any who might wish it ill! The Third System of American seacoast fortification made the Second System look like #2. It was an enormous, long-reaching and hugely expensive endeavor that would ultimately (and arguably) shield the United States from foreign invasion for all time. And it would include Forts Richmond and Tompkins! |

Fort Richmond (technically known as Battery Weed) and Fort Tompkins (technically collectively known as Fort Wadsworth), at the tip of the spear. Support buildings! Extra batteries! Clear fields of fire! That would be a "mine building" between the two forts at a diagonal. |

|

Fort Lafayette, 1904. LOC again! Fort Lafayette, 1904. LOC again! |

|

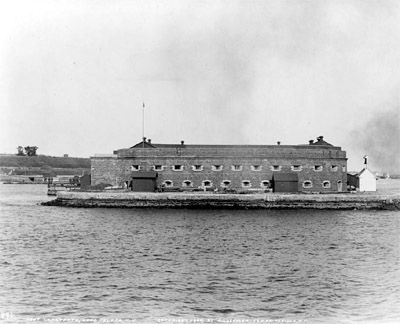

1847 saw the strategic land over the Narrows on Staten Island securely in Federal hands, and work began on what would be the ultimate expressions of Fort Richmond and Fort Tompkins.

On the other side of the Narrows were Fort Lafayette (built 1812-1818) and Fort Hamilton (built 1825-1831, designed by Third System hero Simon Bernard (1779-1839), still an active-duty US Army post). Stationed at Fort Hamilton in the 1840's was a young engineer officer named Robert E. Lee (1807-1870). Lee would go on to great things as General in Chief of the Confederate Army during the American Civil War (1861-1865), but in the 1840's he was a lowly lieutenant in the US Army, tasked with rebuilding Fort Lafayette.

|

|

As Lee was present during the period in which Forts Richmond and Tompkins were undergoing their Third System makeover, it is thought that he may have played a role in their design...gladdening the hearts of alternate history fans, who imagine a fleet of unstoppable Confederate ironclads smashing its way into New York Harbor in 1864, armed with knowledge of weaknesses in the Narrows' defenses that only the man who designed them would know...but Lee had his plate pretty full with Fort Lafayette, and other than his proximity, there doesn't seem to be any evidence to suggest his involvement in the design of Forts Richmond and Tompkins. Good old Joseph Totten, Third System MVP, was responsible for the design of Fort Richmond. |

As the Third System progressed, the designers of America's seacoast fortifications leaned more towards forts with multiple tiers of casemated artillery positions. Many such forts were started, but few were complete by the time the American Civil War rolled around in 1861. Fort Richmond was one of three of the tallest forts constructed during this period, with a whopping four gun tiers: Castle Williams, just up the bay on Governor's Island (which it shares with the starrilty spectacular Fort Jay), and Fort Point at the mouth of the Golden Gate in San Francisco, were also graced with four gun tiers. Fort Richmond, as the seaward-facing component of the Richmond/Tompkins axis, was designed command the narrows with 116 guns, and to mount 24 flank howitzers to defend the gorge, which is just a gross way of saying its landward side. |

|

America's two other four-tiered forts: Castle Williams on Governor's Island in New York Harbor in 1912, and Fort Point in San Francisco, 1865. America's two other four-tiered forts: Castle Williams on Governor's Island in New York Harbor in 1912, and Fort Point in San Francisco, 1865. |

|

Fort Tompkins, meanwhile, had three landward-facing fronts dotted with musket loopholes, intended to deter anyone coming after Fort Richmond. One battery of seacoast cannon was built atop its single seaward-facing wall. Aside from a few flank howitzers, no big guns were mounted to fire upon any landward attackers...which seems a little optimistic, given the nature of warfare at the time, but assumedly the guys who designed this system knew things that I don't.

The red sandstone versions of Forts Richmond and Tompkins were flattened to make room for the forts' new iterations...and that 1663 Dutch blockhouse was finally, mercifully, done away with.

|

Our forts today, from an angle afforded only to those with a drone, a helicopter, the gift of flight, or access to Google Earth. Our forts today, from an angle afforded only to those with a drone, a helicopter, the gift of flight, or access to Google Earth. |

|

As was the case with many a fort on America's shores, Forts Richmond and Tompkins weren't finished in 1861 when the south seceded from the Union, but they were finished enough to be declared "finished!" so that all the dudes needed for their construction could put on blue coats and go be shot at in such scenic locales as Manassas, Virginia.

Some guys stayed behind, however. In 1864 the expanding fort complex was garrisoned by 1900 men: Four small, additional batteries were also built next to the existing forts during the war. |

|

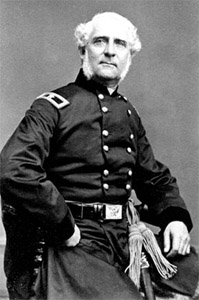

Seven months after the Civil War ended, on November 7, 1865, Fort Richmond was rechristened Fort Wadsworth. Brigadier General James Samuel Wadsworth (1087-1864) had been a wealthy New York landowner who volunteered when the war broke out, served as an aide to Major General Irvin McDowell (1818-1885) at the First Battle of Bull Run (July 8, 1861), and was then put in command of the military district of Washington, DC. |

Wadsworth was given his own command, the 1st Division, I Corps, at the end of 1862, which divison fought with relative acuity at the Battles of Chancellorsville (May 1863) and Gettysburg (July 1863). He was leading 4th Division, V Corps, at the Battle of the Wilderness (May 1864) when he was mortally wounded, and died at a Confederate field hospital on May 8, 1864.

This man was most certainly worthy of having an American fort named after him, and as Fort Richmond hadn't been named after a person, nobody's estate was going to cause trouble over a new name.

A brief enthusiasm for rebuilding America's coastal defenses reared its well-intentioned head in the 1870's. America's military had built itself to a massive state through the Civil War, following which everything had pretty much been dropped and left to rust on the ground where it lay, while Europe's militaries continued to develop and modernize.

The folks in charge of the 1870's armament program recognized that masonry forts were obsolete, and were mostly concerned with mounting guns in various types of earthen batteries: Given the experience of the Civil War, earth was considered to be more difficult to destroy (and vastly cheaper) than masonry.

|

|

James Samuel Wadsworth, looking for all the world like Major Charles Emerson Winchester III, US Army Medical Corps, M.A.S.H. 4077. James Samuel Wadsworth, looking for all the world like Major Charles Emerson Winchester III, US Army Medical Corps, M.A.S.H. 4077. |

|

Information about the short-lived King's Depression Carriage at tiny Fort Foote on the Potomac River, just south of Washington, DC. This early method of making a big gun "disappear" was first installed at Fort Foote. Information about the short-lived King's Depression Carriage at tiny Fort Foote on the Potomac River, just south of Washington, DC. This early method of making a big gun "disappear" was first installed at Fort Foote. |

|

Fort Wadsworth (née Richmond) and Fort Tompkins benefited from this program by having several of their Civil War-era outer batteries refitted to receive new guns: 8-, 10- and 15-inch Rodmans.

During this period Battery Hudson, just to the east of Fort Tompkins, was one of few American forts to be fitted with King's Depression Carriages, by which Rodman Guns could swing down and "disappear" after firing, for safe and cozy reloading behind the parapet. These carriages must not have worked very well, as they were a short-lived phenomenon.

By the end of the 1870's, money for America's bold coastal rearmament program dried up, and many unfinished fortification projects remained unfinished fortification projects. |

|

If the United States thought its coastal defenses were sub-par in the 1870's, by the mid-1880's those defenses were so outmoded that they practically invited invasion. US President Grover Cleveland (1837-1908) may not be remembered today for much, but one thing he did do was turn his Secretary of War, William Crowninshield Endicott (1826-1900), loose. In 1885 Endicott chaired the Board of Fortifications, which investigated America's coastal defenses, determined that they would be ridiculously ineffective if ever called upon to perform their intended function, and recommended a $127 million construction program to correct this. 29 locations along the United States' coast were earmarked for new fortification in 1886, and most of these locations already had fortifications of one stripe or another.

The forts of our current interest were amongst those 29 locations. Between 1896 and 1905, 39 modern, breech-loading guns of various sizes were mounted at thirteen new batteries in the vicinity of Forts Wadsworth and Tompkins. Just to make things as confusing as possible, however, the entire complex was now named Fort Wadsworth, and on February 4, 1902, what had once been Fort Richmond was renamed Battery Weed. Which made sense in the abstract, giving the whole fortified area one name instead of referring to it as Fort RichmondandTompkinsandallthoseotherlittlefortlets- andbatteriesandthings, but...Battery Weed?!

|

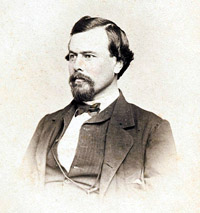

Steven Hinsdale Weed, a New Yorker, was a Brigadier General of artillery in the US Army who died at the Battle of Gettysburg (July, 1863) in defense of Little Round Top. Weed had fought in Florida in 1857 during the Seminole Wars, and helped to deal with the pre-Civil-War unpleasant- ness in Kansas in 1858.

Again, certainly a man worthy of remembrance via American fort-naming. If you were a fort, however (and whom amongst us has never imagined such), whose proud name had been Fort Richmond in the not-so-distant past, would you not consider it just a wee bit of a demotion to be renamed Battery Weed? |

|

Steven Hinsdale Weed, 1863 Steven Hinsdale Weed, 1863 |

|

Part of the impetus of the Endicott Period's defensive improvements involved rising tensions with Spain. We fear the unknown, which is what Spain's naval capabilities were at the end of the 19th century. Had it been the end of the 16th century, America's fears would have been well-founded...but the Battle of Manila Bay (May 1, 1898) revealed that the Spanish navy was about as modern and effective as America's pre-Endicott seacoast fortifications had been. Before the poor state of Spain's navy was divulged, however, there was a universal expectation of the imminent destruction of America's major coastal cities by the Mighty Spanish Armada...and there was no majorer American coastal city than New York. |

An 18cm (7.09") Armstrong Gun at Lévis Fort No. 1 in Québec, Canada. This particular specimen is not of the size installed at Fort Wadsworth, but it's the only Armstrong Gun in whose presence I have ever had the honor to have been, so you get what you get, pilgrim. An 18cm (7.09") Armstrong Gun at Lévis Fort No. 1 in Québec, Canada. This particular specimen is not of the size installed at Fort Wadsworth, but it's the only Armstrong Gun in whose presence I have ever had the honor to have been, so you get what you get, pilgrim. |

|

Work on the modernization of Fort Wadsworth's batteries didn't get underway until 1896, and by the time the United States declared war on Spain in April of 1898, precisely zero of the modern guns with which our fort intended to defend New York were mounted.

In what may have been an unprecedented act of desperation, the United States turned to Great Britain, purchasing four Armstrong Guns: Two 6" and two 4.7" guns. These were modern, medium-caliber, quick-firing breachloading "rifles" that were closer to the size of the Rodman Guns than current American designs, and could thus be more easily fitted onto existing mounts as a short-term solution. |

|

By 1904, Fort Wadsworth's thirteen batteries bristled with a total of 39 fearsome modern guns, ready and waiting to deter whomsoever might try to force the Narrows. Which of course nobody ever did.

Were America's potential seaborne enemies foiled by the massive fortification projects of the 1840's and 1890's, or was no one ever really interested in attacking the coast of the United States in the first place? Hard to say, but Britain most certainly wreaked havoc on American shores during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) and War of 1812 (1812-1815), but nobody wreaked a similar havoc after that, when forts bristled on American shores. |

|

"Taking range" on a 12" gun at Fort Wadsworth, 1908, featuring a spectacularly disinterested artilleryman in the foreground. Thanks again, LOC! "Taking range" on a 12" gun at Fort Wadsworth, 1908, featuring a spectacularly disinterested artilleryman in the foreground. Thanks again, LOC! |

|

...unless you want to count German U-Boats sinking countless tons of American shipping just off of US shores during the Second (1939-1945) and to a lesser degree First (1914-1918) World Wars...but that was really a failure of the US Navy, not coastal defenses.

In 1913, President William Howard Taft (1857-1930) broke ground for what was to be a magnificent National Indian Memorial, which would have been erected on the site of (atop?) Fort Tompkins. This memorial would have involved a museum of native American cultures, topped with a 165-foot statue of an Indian warrior: Perched on the bluffs overlooking the Narrows, this would have been higher than the Statue of Liberty. As fascinating as this project sounds, its proponents ran into trouble when it came to raising money for its construction, and once the First World War broke out in 1914, everyone's attention wandered elsewhere. There are other memorials to Native Americans around the United States today, but this would have been an absolutely huge monument, in one of the most visible places that America had to offer. Sorry, Indians!

|

Fort Tompkins afront, with "Battery Weed" behind. Doesn't that look like some sort of a racetrack in Fort Tompkins? In Fort Wadsworth's Endicott Period overhaul, Fort Tompkins was given over to the Quartermaster, with all the offices, storage, shops and whatnot that went with that most noble branch of the service. All guns were removed from Fort Tompkins at this time, as you simply can't trust a Quartermaster with a gun. Fort Tompkins afront, with "Battery Weed" behind. Doesn't that look like some sort of a racetrack in Fort Tompkins? In Fort Wadsworth's Endicott Period overhaul, Fort Tompkins was given over to the Quartermaster, with all the offices, storage, shops and whatnot that went with that most noble branch of the service. All guns were removed from Fort Tompkins at this time, as you simply can't trust a Quartermaster with a gun. |

|

Perhaps it's just as well that a gargantuan Indian wasn't built atop Fort Tompkins, as the First World War caused a lot of frantic activity at Fort Wadsworth. Being the largest fortification protecting New York, many of the guns at Fort Wadsworth were continually manned and ready to fire during the war, and an enormous Indian lurking behind everybody surely would have been psychologically damaging to the gun crews.

Most American forts that had been blessed with the huge guns of the Endicott Period waved farewell to those guns during the First World War, as these guns were thought to be more usefully utilized as railroad guns in Europe...but for the most part, Fort Wadsworth remained fully armed. The few guns it did send away were swiftly replaced with similar guns from "less-threatened" American forts. |

|

In 1920, several of Fort Wadsworth's guns were removed from service, including the Armstrong Guns at Battery Barbour. Our fort was made into an infantry post in 1924, with just a few caretakers left to watch over the remaining coast artillery. New facilities at Fort Tilden in Queens and Fort Hancock at Sandy Hook, New Jersey mounted monster 12" and 16" guns, whose range, accuracy and destructive power were deemed sufficient to deny the entrance to New York Harbor to any enemy.

The interior of Battery Weed today. Anybody else see a similarity to Fort Popham at Phippsburg, Maine? Well, sort of, I guess. Click here to see a similar angle of Fort Popham.

The Second World War brought some gun swapping to Fort Wadsworth, but the bigger guns at nearby facilities were what kept the Imperial Japanese Navy out of New York Harbor. Fort Wadsworth was used as a "mustering station" for troops heading overseas.

|

As the New York metropolitan area grew in the 20th century, it was recognized that poor, heavily-populated Staten Island, accessible only via the Staten Island Ferry or a lengthy drive (or an even lengthier walk) around the harbor, was unduly separated from the awesomeness of the city. Various plans involving bridges across, and tunnels under the Narrows were bandied about starting in the 1920's, and it was eventually determined that a suspension bridge would be the wisest and most cost-effective option. As military bases existed on both sides of the Narrows, this bridge would need to encroach on military property.

The US War Department, however, wasn't sold on the idea. In the 1930's the military thought that a bridge at this strategic point could block the harbor, which seems a reasonable objection. Following the Second World War, however, all of America's coastal defense guns were scrapped: Missiles and "aeroplanes" would handle coastal defense from thereon. The military finally gave in to civic pressure and sold enough of Fort Wadsworth and Fort Hamilton across the Narrows to the city for bridge construction purposes. |

|

A recent National Park Service map of Fort Wadsworth. Looks like plenty of the fort's infrastructure is still in use by the US Coast Guard and Army! A recent National Park Service map of Fort Wadsworth. Looks like plenty of the fort's infrastructure is still in use by the US Coast Guard and Army! |

|

Looking west over the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. See anything you recognize just to the right of the bridge on Staten Island? Yeah, me neither. Looking west over the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge. See anything you recognize just to the right of the bridge on Staten Island? Yeah, me neither. |

|

Giovanni da Verrazano, Italian discoverer of New York Harbor, finally got his due in August of 1959 when construction of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge began. One unfortunate casualty of this project was little Fort Lafayette, which location was needed to anchor the bridge's eastern support. The bridge was opened for traffic in 1964, and a second, lower deck was completed in 1969.

Fort Wadsworth, meanwhile, was sliding further and further into obscurity. It served as the headquarters for the New York National Guard's anti-aircraft brigade in the early 1950's, and served as a Nike missile headquarters until 1964...which feat it managed to accomplish without ever having any Nike missiles stationed there. The Army, Navy and Coast Guard all used the fort's facilities for various military things during this period. |

|

Fort Wadsworth finally achieved its ultimate manifestation in 1996, when it was turned over to the National Park Service...for the most part. The US Coast Guard and Army still utilize some of the fort's structures. Today much of the fort is available to the public through guided tours. Guided tours, people. No climbing over walls or slipping in through conveniently open gates that say things like "employee entrance only." Only a total creep would do that sort of thing.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|