|

Fort Stevens

Point Adams, Oregon, USA

|

|

|

Constructed: 1863 - 1865

Used by: USA

Conflict in which it participated:

Second World War (in an oblique fashion)

|

In 1803, the United States purchased the Louisiana Territory from France. President Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) immediately sent a party led by Captain Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809) and Lieutenant William Clark (1770-1838), known to all American schoolchildren as the Lewis and Clark Expedition, to explore and map this new acquisition, as well as to find a practical route to the Pacific Ocean...or to the land of dragons and magical flying ocelots, which was suspected to be in that direction as well.

|

|

|

|

Over the next two years, the flintily determined Lewis and Clark Expedition crashed their way from St. Louis to the end of their journey at the mouth of the Columbia River, where it meets the mighty Pacific. They spent the winter of 1805-1806 holed up at Fort Clatsop, named for a local Indian tribe. This was less a fort than a small collection of log cabins, located just a smidge southwest of the future Fort Stevens.

The Expedition spent an uncomfortable four months at Fort Clatsop, vaguely wishing that a ship might appear and carry them home, but not so much as a single magical flying ocelot showed up to ease their burden. They walked back to St. Louis through most of 1806, no doubt happy to leave Fort Clatsop behind them.

Lewis and Clark, despite their frigid, hungry heroism, were not the first to "discover" the mouth of the Columbia River. The first documented sighting was in 1775, by Spanish naval explorer Bruno de Heceta (1743-1807). Operating on de Heceta's directions, British fur trader Captain John Meares (1756-1809) tried to find the river in 1788, but determined it did not exist. Meares named Cape Disappointment, his location on the Pacific coast where he came to this crushing determination...which is actually the northern end of the mouth of the very river for which he had been looking. Google Maps, where were you when Cap'n Meares needed you?

|

Fort Astoria in 1813, drawn by Gabriel Franchére in 1854. Fort Astoria in 1813, drawn by Gabriel Franchére in 1854. |

|

American maritime fur trader Robert Gray (1755-1806) holds the distinction of being the first "European" to sail upon the Columbia River: The river was in fact named for his ship, the Columbia Rediviva. That this river was first sailed upon by Americans was later used by the United States to support its claim to the Oregon Region, which was also claimed by Britain, Spain and Russia.

The fur trade was a lucrative one, and by 1811 John Jacob Astor's Pacific Fur Company had a presence at the mouth of the Columbia, in the form of Fort Astoria. This was the first American-owned settlement on the Pacific coast. |

|

Which shortly became the first British-owned settlement on the Pacific coast, when, shortly after the start of the War of 1812 (1812-1815), Jacob Astor's business was bought up by a Montreal-based fur trading company. The fort's new owners renamed it Fort George, which was the standard name for about 80% of all British forts during the period in question.

A variety of weird territorial claims and counterclaims took place following the War of 1812 in the Pacific Northwest. The 16-gun sloop of war USS Ontario arrived at Fort Astoria in August of 1818, nominally claiming both the northern and southern banks of the Columbia River for the United States...a claim that Great Britain understandably did not recognize.

|

When the Adamis-Onís Treaty of 1819 betwixt the United States and Spain ceded Florida (along with the stellar Castillo de San Marcos) to the US, it also handed over territorial rights to all discoveries made by Spain on the North American continent north of the 42nd parallel (which included the Columbia River)...or so the United States strenuously argued. Finer points of the law notwithstanding, Britain still felt pretty strongly that the Oregon Territory was part of Canada. Added to all of this was that Fort George was essentially a commercial entity, not a military fort that belonged directly to Britain or the United States. Ownership of the fort was passed between a few different Canadian fur-trading firms for a couple of decades, while Britain and the United States "shared custody" of the Oregon Territory. Finally in June of 1846 US President James K. Polk (1795-1849) spearheaded the Oregon Treaty, which set the boundary between the US and Canada at the 49th parallel, which remains the border today. Though the right of continued operation in this region was guaranteed to the Hudson's Bay Company, a Canadian fur trading firm that owned Fort George at that time, it opted to sell all its possessions south of the 49th parallel. The Columbia River finally flowed in red, white and blue. Which are the colors of the flag of the United States, in case anyone here is unfamiliar. |

|

The Internet is short on pictures of the actual Fort Stevens, but long on pix of the wreck of the Peter Iredale. A British merchant ship, the Iredale ran aground close to Fort Stevens on the night of October 25, 1906. Once 'twas determined to be unshiftable, it was sold for scrap and today all that remains is this fetching section of the bow, a few ribs and two of the ship's four masts. |

|

In the 1820's, fur trappers and traders pioneered what would become known as the Oregon Trail, connecting the eastern United States with the wild 'n' wooly Oregon Territory. The city of Portland, at the confluence of the Columbia and Willamette Rivers, was officially founded in 1845, and developed into a major port of the Pacific Northwest. During the Second World War (1939-1945), the shipyards of Portland churned out a steady stream of Liberty Ships, which were enormous cargo vessels...making the mouth of the Columbia River a location in desperate need of defense..

During the US Civil War (1861-1865), commerce raiders of the Confederate States Navy, such as the CSS Shenandoah, sailed the north Pacific, their mission to disrupt Union commercial activity. The spectre of enemy ships appearing at unexpected locations naturally freaked out Union authorities, and Cape Disappointment was armed with smoothbore cannon in 1862, lest the Shenandoah take an unhealthy interest in Astoria's salmon industry.

|

Thank goodness somebody got a picture of the fort of our current interest! Granted, grassy earthen walls aren't terribly photogenic, but come on, everybody who's ever been to Fort Stevens with a digital camera and subsequently uploaded their pictures to the Internet!!! Thank goodness somebody got a picture of the fort of our current interest! Granted, grassy earthen walls aren't terribly photogenic, but come on, everybody who's ever been to Fort Stevens with a digital camera and subsequently uploaded their pictures to the Internet!!! |

|

By 1863, it was determined that an actual fortification was needed to protect the mouth of the Columbia River, not only from Confederate tomfoolery but due to increasing tensions with Great Britain. The Fort at Point Adams was begun in July of 1863 and completed in April of 1865. Later in 1865 the fort was officially named for Isaac Stevens (1818-1862), who had served as the first Governor of Washington Territory from 1853 to 1857. Stevens was killed in action at the Battle of Chantilly on September 1, 1862, and also had another fort named after him. The northernmost work in the Defenses of Washington DC, this other Fort Stevens holds the distinction of being the only section of DC's defenses that was attacked by the Confederacy in July of 1864, as none other than Abraham Lincoln (1809-1865) watched amusedly from behind the fort's walls. |

|

Starfort enthusiasts of a more discerning nature will have by now noted that Fort Stevens is not of the classic starfort design. Even now they are doubtless composing pithy commentary to inform me of this, but I assure you that I am aware. It is instead a five-sided earthwork, with bastions on each end and a salient point facing the Columbia River. The entire work was surrounded by a wet ditch (which in earlier times would have been referred to as a "moat"), and the only entrance was protected by a drawbridge. Fort Stevens was designed to mount 29 guns.

The fort's garrison during the Civil War mounted a total of ten guns: A 15" Rodman Gun (the largest available at the time) was installed at the salient point, and nine other smaller Rodmans were mounted along the walls. Sadly, no Confederate nor British nor any other belligerent Navy poked its nose into the Columbia River during the Civil War.

By June of 1867 there were a total of 26 guns of varying calibres mounted at Fort Stevens. These were kept operational and fired on occasion until 1882, though little else was done to maintain the rest of the fort. The garrison left, and the dilapidated Fort Stevens was turned over to a single caretaker.

There was a brief period of congressional interest in modernizing America's seacoast defenses in the 1870's. The defenses at Fort Cape Disappointment were slightly improved and renamed Fort Canby in 1875, but money and interest in military endeavors in the years following the immensely exhausting Civil War didn't last long enough to complete much of anything.

|

Thank goodness for William Crowninshield Endicott (1826-1900). The Secretary of War for the Grover Cleveland (1837-1908) administration, Endicott chaired the Board of Fortifications in 1885. This august body was tasked with preparing the United States to defend its shores into the futuristic 20th century, by identifying its most strategically important locations, and then fortifying the living snot out of them. A great many of the 29 identified locations were places that already had starforts installed. The Endicott Period, which lasted roughly from 1885 to 1905, furthered the sacred cause of the American starfort not only by re-emphasizing the crucial nature of these locations, but in many cases by building new gun batteries in and around existing starforts. While this process was not pretty, and has frequently been bemoaned by yours truly, the machinations of the Endicott Period greatly extended the useful lives of many American starforts. |

|

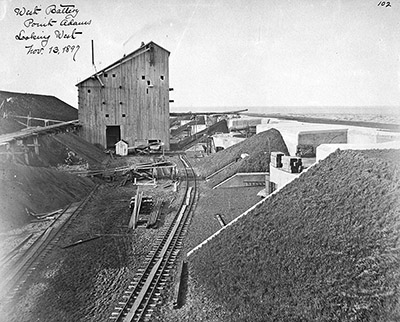

Fort Stevens' West Battery (soonafter renamed Batteries Mishler, Walker and Lewis), under construction in 1897. At least I hope it was still under construction, and that huge obnoxious wooden structure behind the battery was temporary. Because these Endicott Period batteries were supposed to be difficult for attacking ships to identify, and that big dumb wooden thing sure seems as though it would be easy to see for miles around. Fort Stevens' West Battery (soonafter renamed Batteries Mishler, Walker and Lewis), under construction in 1897. At least I hope it was still under construction, and that huge obnoxious wooden structure behind the battery was temporary. Because these Endicott Period batteries were supposed to be difficult for attacking ships to identify, and that big dumb wooden thing sure seems as though it would be easy to see for miles around. |

|

The mouth of the Columbia River was one of the lucky strategic locations to benefit from the $127 million (which would be over $3 billion today) Coastal Fortifications Program. While eight new batteries mounting everything from 3" quick-firing guns to 12" mortars to 10" disappearing rifles were being built in and around Fort Stevens, Fort Columbia was built across the river from 1896 to 1904, on the Chinook Point promontory. This "fort" consisted of three batteries, mounting 3", 6" and 8" guns.

|

Fort Columbia, on the northern shore of the Columbia River, as it appears today. Fort Columbia, on the northern shore of the Columbia River, as it appears today. |

|

Fort Canby at Cape Disappointment was also upgraded, with two batteries of 6" disappearing guns: Another battery mounting four 12" mortars was added in 1918. The Columbia River Harbor Defense System comprised the newly Endicotted Forts Canby, Columbia and Stevens. The Columbia River was ready to be vigorously defended against all comers!

Nobody came. After the initial fear of imminent Spanish invasion (which had provided much of the impetus for the frantic fortification of the Endicott Period) died down, Fort Stevens was garrisoned through much of the 1910's with around 500 men. As war clouds loomed in 1917, however, that number was increased to nearly 3,000. As was the case at many Endicott fortifications, several of the fort's giant gun tubes were removed and shipped to Europe. |

|

This removal of military hardware only took place once it had been determined that an invasion of the United States was highly unlikely in the present conflict. From what I have seen, few if any of these American gun tubes were ever used for their intended purpose in Europe during the First World War (1914-1918). They did, however, impress America's allies by illustrating the US' willingness and ability to produce and then needlessly waste giant expensive things.

|

As usual, interest in all things military ceased after the war. Fort Stevens' garrison was reduced to a 60-man Caretaking Detachment, with only two men each caring for Forts Columbia and Canby.

The Columbia River Harbor Defense System was reinvigorated with the coming of the Second World War (1939-1945). Garrison numbers started to increase in 1937, and by 1942 there were nearly 3,000 soldiers once again manning the guns.

One of the ironies of the vast American fortification program of the early 20th century was that none of these ruinously expensive monuments to defensive technology were ever tested by an enemy...except Fort Stevens.

|

|

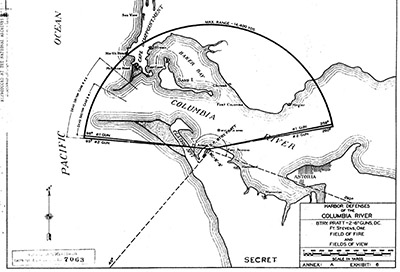

The field of fire of the two 6" disappearing guns of Fort Stevens' Battery Pratt. A range of 8 miles was impressive for 1897, but dangerously obsolete by the start of the Second World War. The field of fire of the two 6" disappearing guns of Fort Stevens' Battery Pratt. A range of 8 miles was impressive for 1897, but dangerously obsolete by the start of the Second World War. |

|

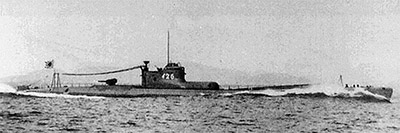

On the night of June 21, 1942, a submarine of the Imperial Japanese Navy, the I-25, followed a fleet of fishing boats through the minefield that had been carefully laid in the approaches to the Columbia River. The I-25 surfaced, parked itself 10 miles west of Fort Stevens and opened fire with its deck gun.

|

The I-26, a B-1 type submarine of the Japanese Imperial Navy. Assumedly this is virtually identical to the I-25, which is the specific submarine of our current interest, as this is the image that Wikipedia provides to illustrate the I-25. Sure, I could just Photoshop that 6 into a 5, but that would be dishonest. The I-26, a B-1 type submarine of the Japanese Imperial Navy. Assumedly this is virtually identical to the I-25, which is the specific submarine of our current interest, as this is the image that Wikipedia provides to illustrate the I-25. Sure, I could just Photoshop that 6 into a 5, but that would be dishonest. |

|

Seventeen 5.5-inch shells were fired at Battery Russell, Fort Stevens' southernmost Endicott battery. The fort's garrison had leapt from their beds and manned their guns, but the order was given not to return fire.

Various reasons for the decision to sit quietly while being bombarded have been floated, but the decision was the right one. The I-25, on a reconnaissance mission to determine how well the mouth of the Columbia River was defended, was out of range of Fort Stevens' vintage guns. |

|

Plus, in the dark it was impossible to pinpoint the sub's exact location...so if Battery Russell had returned fire, its 10" shells would have plunked into the ocean two miles short of a tiny, invisible target that they would have been extremely unlikely to hit even if Fort Stevens' guns had the range, and the I-25's captain, Lieutenant Commander Meiji Tagami, would have reported, correctly, that a Japanese fleet could sit ten miles offshore with impunity and pound Fort Stevens into oblivion.

|

Ultimately, the only damage Fort Stevens suffered in this only instance of the mainland of the United States being directly attacked since the War of 1812 (1812-1815) was to some power and telephone lines, and the backstop of Fort Stevens' baseball field. The I-25 went home unharmed, but without any useful information about the defenses of the Columbia River.

The I-25 enjoyed an exciting couple of years of operations during the Second World War. It participated in the attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941, by screening the Japanese aircraft carriers as they departed after the raid.

|

|

Battery Russell in its present form. Battery Russell in its present form. |

|

The I-25 had a seaplane that it somehow stored when not in use, which it sent off to drop incendiary bombs on the pine forest near Brookings, Oregon in September of 1942, in an attempt to start a wildfire that was assumedly hoped would consume the entire continent...the only instance in which mainland America was bombed during the war (no such wildfire was caused). The I-25 was finally sunk in 1943 off the New Hebrides, northeast of Australia, by the destroyer USS Ellet.

Had the I-25 returned to the mouth of the Columbia at the end of 1944 and tried to repeat its historic feat, it would have been surprised to find itself within the range of fire of Fort Stevens. Two 6-inch guns of a more contemporary design (and with a range of fifteen miles) had been installed in a new battery, whimsically named Battery 245, to the west of Fort Steven's older batteries, by October of 1944.

|

A 6-inch gun on a Shielded Barbette Carriage at Battery 234 at Fort Pickens, Pensacola, Florida. This is the same type of gun that was mounted at Fort Stevens' Battery 245 in 1944. I only include this picture because I want to impress everyone with the fact that I visited Fort Pickens in May of 2016. Are you impressed? Mission accomplished. A 6-inch gun on a Shielded Barbette Carriage at Battery 234 at Fort Pickens, Pensacola, Florida. This is the same type of gun that was mounted at Fort Stevens' Battery 245 in 1944. I only include this picture because I want to impress everyone with the fact that I visited Fort Pickens in May of 2016. Are you impressed? Mission accomplished. |

|

Fort Stevens was deactivated in June of 1947, and all its guns were removed by the end of the year. Shortly after the start of the Korean War (1950-1953), wholly justified fears of a massive North Korean invasion of the west coast of the United States prompted the establishment of Fort Stevens Air Force Station.

This was not an airbase with actual airplanes, but a radar surveillance station. Could the radar of 1950 surveil North Korea from all the way across the Pacific Ocean? Perhaps not, but it could listen for the telltale emissions of an enormous fleet of North Korean landing craft. This hi-tech listening post was moved to an Air Force base in Washington in early 1952.

Fort Stevens was passed to the US Army Corps of Engineers for a spell, until it finally became the responsibility of the Oregon Parks and Recreation Department in 1975. |

|

Today Fort Stevens State Park is an immensely popular tourist and camping attraction. Thanks so much to Peter Presford of Postern Magazine for pointing me towards Fort Stevens!

|

A 6-inch gun on disappearing carriage at Fort Stevens' Battery Pratt. A 6-inch gun on disappearing carriage at Fort Stevens' Battery Pratt. |

|

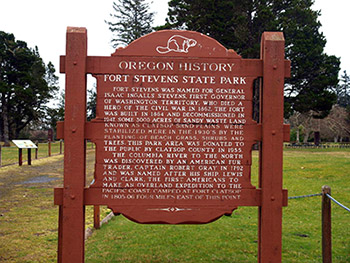

An historical sign at Fort Stevens State Park. But then you probably already figured that out. An historical sign at Fort Stevens State Park. But then you probably already figured that out. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|