Fort MifflinPhiladelphia, Pennsylvania Fort MifflinPhiladelphia, PennsylvaniaBuilt 1795-1802

Fort James JacksonSavannah, Georgia Fort James JacksonSavannah, GeorgiaBuilt 1808-1812

Fort MonroeHampton, Virginia Fort MonroeHampton, VirginiaBuilt 1819-1834

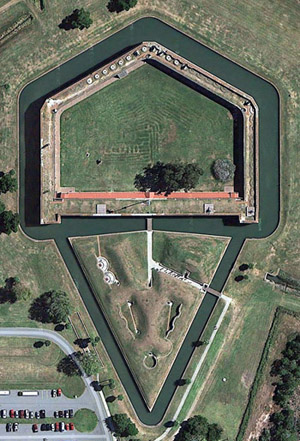

Fort JacksonPlaquemines Parish, Louisiana Fort JacksonPlaquemines Parish, LouisianaBuilt 1822-1832

Fort MontgomeryRouses Point, New York Fort MontgomeryRouses Point, New YorkBuilt 1844-1871

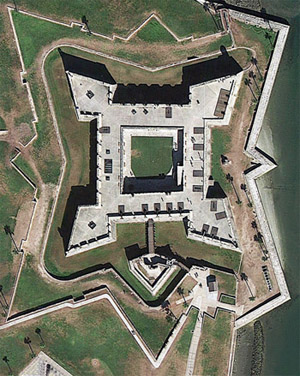

Fort PulaskiCockspur Island, Georgia Fort PulaskiCockspur Island, GeorgiaBuilt 1829-1847

Fort Zachary TaylorKey West, Florida Fort Zachary TaylorKey West, FloridaBuilt 1845-1866

Fort JeffersonDry Tortugas, Florida Fort JeffersonDry Tortugas, FloridaBuilt 1846-1876

Fort DelawarePea Patch Island, Delaware Fort DelawarePea Patch Island, DelawareBuilt 1848-1859

Fort MaconBeaufort, North Carolina Fort MaconBeaufort, North CarolinaBuilt 1826-1834

Castillo de San MarcosSt. Augustine, Florida Castillo de San MarcosSt. Augustine, FloridaBuilt 1672-1676

|

|

"...you want a MOAT around this vastly complicated, ruinously expensive fortification you're designing? Bernard, you are aware that it's 1818, not 1418, right?!"

-President James Monroe, upon being shown

Simon Bernard's initial plans for Fort Monroe, 1818* A moat surrounding a fortified position seems, at least to the American ear, like a curiously medieval concept. Castles have moats, not something as scientifically modern as a starfort!Ah, but starforts do indeed have moats, though the moated starfort is primarily a European phenomenon. Italy, the Netherlands, France, Spain, Portugal and England were of course constructing starforts hundreds of years before there was such a thing as a United States, and when nations that had once built castles built starforts, certain ideas about fortification carried over in ways that they did not in the New World.

(Another example of an older European fortification concept weaseling its way into the starfort era is the guérite, with which you are more than welcome to familiarize yourself at Starforts.com's Guérite page.) The moat is thought to have first been utilized by the Egyptians, around castles such as Buhen, circa 1860BC. Evidence of moats have been found at archaeological sites across Southeast Asia, one example being the settlement at Noen U-Loke in what is today Thailand, dating to what is vaguely described as somewhere in the vicinity of 1000BC. Moats around ancient castles were certainly there for military reasons, while those at settlements were more likely to serve an agricultural purpose. The word moat comes from the Old French motte, meaning mound or hillock. The term first applied to the hill on which a castle would be erected, but was later used to describe an excavated ring at the base of the hill: a "dry moat." The dry moat served to hinder medieval engines of war, such as seige towers or battering rams, both of which needed to get close to the object of their desired conquest to operate in a properly conquestatory (conquestatious?) manner. While even a dry moat would serve as an effective obstacle for an attacking force, put water in it and your attackers are inconvenenced and wet! To fill one's moat, however, one needs a convenient water source. If one is fortunate enough to either have slaves at one's disposal or simply not give a hoot about the wellbeing of one's subjects, one could fill a moat at the top of a mountain by way of a bucket brigade, but such a closed system would eventually get pretty smelly. Not to mention the nuisance of needing to slaughter one's slaves and/or subjects when they rioted over carrying endless buckets of water. The secret to a wet moat that both hinders an attacker and doesn't make your garrison hideously ill, is to keep that water flowing. The necessity of a constant source of fresh water pretty much dictates whether a fortification can have a wet or dry moat, though in some cases a plumbing system for an intended wet moat has worked so poorly that a fort's engineers just threw up their hands and bellowed, "DRY MOAT! WE'LL JUST HAVE A DRY MOAT!" in whatever language they spoke. One example of this is Fort Macon, about which we'll read more later. |

|

|

The masonry starforts of the United States were almost exclusively built for the purpose of seacoast defense. Many of the British and French starforts built before the US Revolutionary War (1775-1783) concentrated on the inland waterways connecting what would later become the US and Canada, but once there was a United States, the mission was to prevent a hostile force from landing on its shores. What does one have plenty of when one builds one's starfort next to the ocean? One might correctly answer jellyfish, but in this case I'm talking about an endless supply of water.

Unfortunately, it's frequently not that simple. Unless an engineer is fortunate enough to be tasked with building a starfort that's practically in the body of water it's supposed to be defending (as with Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas), he will have to devise some scheme by which a constant supply of fresh water can be directed to flow effortlessly through the intended moat. Of the many feats of engineering skill of which the American military was capable in the 19th century, coming up with a good way of accomplishing a surgically hygenic moat was not one of them. I have visited eight of these moated American starforts (and both of those on the Honorable Moat Mention list), and while three of them today possess the most lovely, fresh-smelling moats that modern semiaquatic technology can provide ( Monroe, Pulaski and Delaware), I was regularly assured that this was not always the case. In most cases, engineers would have a single channel dug which connected the moat in question to the nearby body of water: In theory, this would accomplish a free flow of water, which would flush out the moat at a constant rate. Naturally, results varied, but not by much. Fort Delaware had one of the first modern plumbing systems in the United States when it was completed in 1859: Indoor plumbing! Modern efficiency and convenience! Unfortunately, the garrison's wasteful emanations were drained into the moat, where they generally hung around and grew in size and stature for a few weeks or so...as a single ditch, regardless of how nicely masoned it may be, doesn't magically promote a cleansing flow of water. Particularly in the hot summer months, the men of Fort Delaware tended to become much more familiar with their own poop than the majority may have wished. The moat of Fort Pulaski is today a most robust, healthy and slightly brackish-tasting wonder. The channel from which this moat supposedly gets its fill from the Savannah River, however, is a curiously weedy, choked little thing. However Pulaski's hearty moat is currently being filled and maintained, one suspects that it is not via that channel. Philadelphia's Fort Mifflin has an impressive array of rusty ironmongery dedicated to the control of its moat, but the moat today more resembles a sluggish series of vegetated ponds than anything else. |

|

Fort Delaware's moat channel Fort Delaware's moat channel

Fort Pulaski's lovely moat and diminutive channel

Fort James Jackson's moat

Fort Mifflin's moat channel hardware |

Another issue related to the enmoating of one's starfort is, of course, the garrison's need to get across the moat and into the fort, preferably without getting wet. Today all of these forts have permanent, nonmoving bridges across their moats, but in the days when it was thought that there might eventually be some sort of offensive action directed against them, these forts were either equipped with the classic drawbridge; some sort of walkway that was carefully covered by a series of guns; or, in a couple of cases, a swing bridge.

Fort Montgomery and the non-moated Fort Clinch on Amelia Island, Florida, are the only two examples of American starforts built with swing bridges. Though the concept of a twirling bridge that would be hilariously pivoted in such a manner as to render it uncrossable by an attacking force initially seemed completely ridiculous to me, after some study I have decided that it is only a slightly ridiculous concept. Given that a drawbridge is the obvious, proven solution to such a challenge as keeping the unwanted out of one's starfort, the addition of a complicated swing bridge system seems an odd choice indeed. |

|

The swing bridge in a decidedly un-starfortish situation. Thanks, Wikipedia! The swing bridge in a decidedly un-starfortish situation. Thanks, Wikipedia! |

The moats of the starforts on this list are of course wet moats, but a dry moat is a considerable obstacle as well. Virtually all American starforts originally had some sort of ditch around them, either as a standard moat-style obstacle or as a position from which infantry outside the fort might fight, as was the case with Fort McHenry at Baltimore.

|

|