|

Fort Scammell

House Island, Portland, Maine, USA

|

|

|

Constructed: 1808, 1850

Used by: USA

Conflict in which it participated:

War of 1812

|

Alexander Scammell (1742-1781) was a Massachusetts attorney and officer in the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783). He is double starfort royalty, as he participated in the raid on Fort William and Mary (renamed Fort Constitution in 1808) in Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in December of 1774, and here we are talking about another starfort named after him. Colonel Scammell was killed during the Siege of Yorktown (October of 1781), the highest-ranking American officer to die in that battle. |

|

|

|

Ye Province of Maine was more or less established in 1622, when Sir Ferdinando Gorges (1565-1647) received a land patent from the Plymouth Council of New England which included the future US state. Acting as an agent for Gorges was naval explorer Christopher Levett (1586-1630), who settled what would become the city of Portland in 1623. After leaving ten men behind to play the role of victorious settlers, Levett returned to England, whereupon he wrote a book about his adventure, hoping to stoke interest in his settlement. That interest never materialized, however, and his settlers dematerialized into nothingness. Their fate is unknown, but we're pretty sure they didn't build any starforts.

|

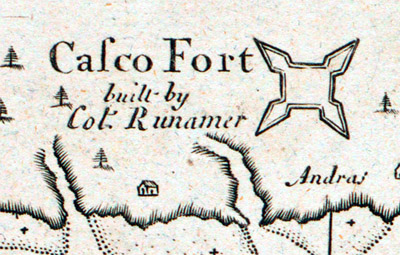

Fort New Casco, or Casco Fort, or perhaps Cafco Sort, from an age when f's and s's were interchangeable. Fort New Casco, or Casco Fort, or perhaps Cafco Sort, from an age when f's and s's were interchangeable. |

|

Fortunately, other people did. Different English persons established the lil' fishing and trading village of Casco in 1632, and built equally lil' Fort Loyal in 1678, following an unpleasant interaction with the local Indians in which Casco was destroyed. Consisting of four wooden blockhouses and eight guns, Fort Loyal was immolated by the French and their Indian allies in 1690, and its inhabitants were massacred just to make sure everyone got the point.

Fort New Casco was built in 1698 by Dutch engineer Wolfgang William Romer (1640-1713), who was in the Americas building various things in and around New York City. |

|

Romer was also responsible for the construction of Fort William and Mary at Portsmouth, New Hampshire... and what would become Fort Independence in Boston. Which is pretty noteworthy, but you get American starforts named after you for dying heroically/patriotically in battle, not for building starforts. Just ask Simon Bernard (1779-1839) and Joseph Totten (1788-1864). October of 1775 saw Portsmouth, then incorrectly known as Falmouth, torched by the Royal Navy. This made a degree of sense, as there was a war going on at the time, specifically the American Revolutionary one. After the war, there was enough Falmouth left for some of it to be renamed Portland, after the Isle of Portland off the Dorset coast of England. That Portland has a major starfort in the form of Verne Citadel, built 1857-81, which in 1949 was rechristened HMP the Verne, a men's prison that still operates today. |

Portland developed as a commercial port and shipping center, doing much business with Britain, as the British were the ones most energetically plying the seas at the start of the 19th century. Britain and France were embroiled in the various wars that arose from the latter's revolutionary wackiness, however, and many American sailors were getting caught in the crossfire. Britain's Royal Navy felt it perfectly reasonable to impress into its service any sailor who had previously been in its employ, which generally translated into thousands of American sailors being nabbed for this purpose at gunpoint on the high seas. US President Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), though being screamed at from several directions to declare war on Great Britain over impressment and others issues, semiwisely decided to try a "commercial warfare" response. The Embargo Act of 1807 was the embodiment of this response.

|

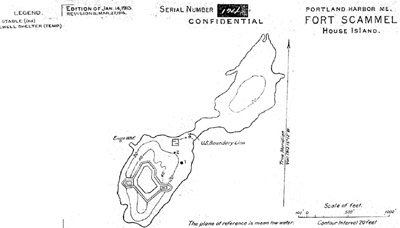

A plan of the original Fort Scammell, from 1808. Thanks as always to Fortwiki.com, fount of all such digitized documents! A plan of the original Fort Scammell, from 1808. Thanks as always to Fortwiki.com, fount of all such digitized documents! |

|

|

This embargo was intended to economically damage both Britain and France, whose navy was also playing fast and loose with American neutrality, by outlawing any American trading with these, and, comically, all nations. In practice, however, the Embargo Act of 1807 primarily outraged American businessmen in new England, whose livelihoods were inextricably linked with British shipping. Many businessmen, including those in Portland, found ways to work around the embargo, continuing to trade with Britain and France despite the illegality of such behavior.

The British and French, meanwhile, may or may not have actually noticed they were being embargoed. Once somebody so informed them, these events seemed to illustrate what a ridiculous form of government this new American "Republic" was, a thought which was simultaneously occurring to those New England businesspersons who were so negatively impacted. Terrible idea or not, we can thank the Embargo Act of 1807 for inspiring the construction of Fort Scammell! The authorities desired not only to defend Portland from foreign incursion, but to be in a position to enforce the embargo...and what better way to achieve both of these goals than by building a starfort?

|

The blockhouse at Fort Edgecomb, just a wee bit northeast of Portland, in May of 2015. Fort Scammell's blockhouse looked like this one, only whiter. Trust me. The blockhouse at Fort Edgecomb, just a wee bit northeast of Portland, in May of 2015. Fort Scammell's blockhouse looked like this one, only whiter. Trust me. |

|

But in this case, they chose to build a circular, masonry battery of fifteen guns and one mortar, with a blockhouse behind it. This particular form of blockhouse, an example of which can be seen to the left, was very popular in New England during the period in question: Cheaper to make than a masonry fort, these blockhouses were painted white for a high degree of visibility...which is anathema to the concept of the American starfort, for the most part, but these fortifications were meant to be seen, as undeniable evidence that the area was DEFENDED.

But, like the other similar blockhouses built along New England's coast at the start of the 19th century, Fort Scammell's was first used to enforce the unpopular embargo. Because everybody knew that those greedy New Englanders would be up to no good unless they were supervised. |

|

The construction of both Fort Scammell and its nearby brother Fort Preble at Casco Bay, the mouth of Portland's harbor, fell to Henry Alexander Scammell Dearborn (1783-1851). The son of Revolutionary War hero and US Secretary of State Henry Dearborn (1751-1829), Henry Junior was, amazingly, named for the starfort whose construction he would one day oversee! Or maybe he was named after Henry Senior's good friend and buddy, Alexander Scammell. Ultimately the Embargo Act of 1807 did far more damage to the United States than to its intended inflictees, and it was repealed in 1809 when President James Madison (1751-1836) was sworn into office...upon which everyone, probably including Thomas Jefferson, breathed a huge sigh of relief. |

The United States declared war on Great Britain in June of 1812, the embargo having failed to chastise the beastly lobsterbacks. While the Royal Navy did various outrageous(ly successful) things to the United States during the course of this conflict, messing with Portland was not one of them. Nonetheless, Fort Scammell holds the cherished distinction of being the only one of Portland's forts to have traded shots with a British warship during the War of 1812!

...sort of. This incident took place in August of 1813, when a British privateer (a semiwarship not directly involved with the Royal Navy, yet capable of Royal Navylike actions) attempted to abscond with a small private ship within sight of Fort Scammell.

|

|

45° of Fort Scammell, from its eastern bastion. Google Maps, I cannot say enough nice things about you. When you work properly. 45° of Fort Scammell, from its eastern bastion. Google Maps, I cannot say enough nice things about you. When you work properly. |

|

Our fort's garrison fired a shot at the British ship, which duly fired back. No shots hit home, and history seems curiously silent as to whether this dastardly act of pseudopiracy was foiled or not: One imagines that both sides said "Well, that was fun!" and carried on with their business.

Fort Scammell sat and crumbled for a few decades after the War of 1812 ended by being called the War of 1814 (even though it really ended in 1815), until a renewed interest in the 1840's saw the masonry flanks of the fort's circular battery extended around to the rear of the fort, providing protection on its landward side. This improvement process stretched into the 1850's.

The secession of eleven US states in 1861 caused not only the American Civil War (1861-1865), but a sudden recognition that a whole lot of vital trade emanating from New England's seaports, not to mention much shipbuilding enterprise, was vulnerable to a theoretically marauding Confederate navy. Grandiose plans for a series of impregnable, three-tiered, casemated seacoast fortifications were immediately drawn up by Union gentlemen with impressive facial hair, the construction of which got underway in 1862.

|

Fort Scammell sometime betwixt 1900 and 1910, looking much as it did during the Civil War: That is to say, black and white. Fort Gorges also makes a shy appearance to the left, behind House Island. Thanks, Library of Congress! Fort Scammell sometime betwixt 1900 and 1910, looking much as it did during the Civil War: That is to say, black and white. Fort Gorges also makes a shy appearance to the left, behind House Island. Thanks, Library of Congress! |

|

Once again, Fort Scammell would not follow the herd. While multitiered monstrosities were being constructed nearby (Fort Preble and Fort Gorges, also protecting Portland harbor, both got at least a bit of the three-tier treatment), army engineer Thomas Lincoln Casey (1831-1896) went a different route with Fort Scammell's resurrection. Having overseen the construction of the non-standard-shaped Fort Knox at Bucksport, Maine since 1844, Casey was an innovator. And his innovation for Fort Scammell seemed odd indeed, but would probably have been as effective as any other fortification being built at the time. Fort Scammell was rebuilt as two masonry bastions, on House Island's east and west sides, connected by substantial earthwork walls. A similar third bastion was planned, but never built. |

|

As originally planned, each of the fort's bastions was to be three tiers of casemated death for attacking ships, but only a single tier faced the west, and two tiers to the east when the work was deemed complete...and both were open to the elements above and behind. Ultimately, precisely zero of the fortifications proposed during this period were built to their original specifications: Fort Gorges a little to the west of Fort Scammell in Portland Harbor got two tiers; Fort Preble barely managed a single tier, as did Fort Constitution at Portsmouth, New Hampshire; Fort Popham in Phippsburg, Maine made it to two; and they just gave up on Fort McClary at Kittery, Maine in 1868, without even completing a single tier. Which is sad, but at least it was tierless. Portland Harbor's defenses weren't used as they were intended during the Civil War, but there was a little Confederate-inspired excitement in the harbor, in June of 1863. The Confederate raiding ship CSS Tacony captured a fishing vessel called the Archer off the coast of Maine, and entered Portland Harbor posing as fishermen. They planned to do something to disrupt Portland's commercial shipping capability, which plan's first and only step was the seizure of a Revenue Service cutter, the Caleb Cushing. The element of surprise lost, the Confederates-dressed-as-fisherman-in-a-US-revenue-cutter sailed out to sea, pursued by a portion of Fort Preble's garrison and deputation of armed, infuriated Portlanders in a variety of vessels. The raiders were captured and held at Fort Preble, but were secreted away in the night to Fort Warren in Boston Harbor, as their presence in Portland was made impossible due to local ire. |

Thomas Lincoln Casey would go on to complete construction of the Washington Monument in 1878, a project that had been stalled since 1854. He served as the US Army's Chief of Engineers from 1877 to 1881, a post previously held by starfort notables Alexander Macomb (namesake of the fantastic yet tragically abandoned Fort Macomb outside of New Orleans) and Joseph Totten, who played a vital role in the construction of many of America's coolest starforts. If things had gone as planned when the new Fort Scammell was designed, it would have mounted 64 guns and seven mortars. |

|

You probably never expected to see casemates inside of Fort Scammell! You probably never expected to see casemates inside of Fort Scammell! |

|

Very little armament made it into the fort during the Civil War, however, as events such as the relatively easy destruction of previously-thought-to-be-impregnable third system American forts as Fort Pulaski and Fort Macon forced those making fortification decisions to rethink their approach. Which was fortunate, as the Confederacy's fleet of steam-powered battle dirigibles never made it to Portland during the war. A brief enthusiasm for modernizing America's seacoast defenses in the 1870's brought new life to Fort Scammell. 10" and 15" Rodman Guns were all the rage during this period, as a great many had been manufactured during the Civil War, with relatively few having been used. These guns were considerably larger and more powerful than their predecessors, and much improvement had to be undertaken at existing forts before they could be mounted. An earthwork battery was duly constructed at the southern tip of House island for this purpose, connected to the rest of the fort with earthwork walls. Larger magazines were built, and the fort's east and west bastions were enclosed with vaulted ceilings. |

A super-secret War Department plan of Fort Scammell from 1916. Why the War Department was even bothering to draw Fort Scammell in 1916 is anybody's guess, although they did make an effort to install some anti-aircraft guns on House Island in 1917. Sorry, but you'll have to burn your computer and gouge out your eyes after viewing this secret document. A super-secret War Department plan of Fort Scammell from 1916. Why the War Department was even bothering to draw Fort Scammell in 1916 is anybody's guess, although they did make an effort to install some anti-aircraft guns on House Island in 1917. Sorry, but you'll have to burn your computer and gouge out your eyes after viewing this secret document. |

|

The United States abandoned all fortification projects in the mid-1870's, leaving unfinished a bastion at Fort Scammell's northern extent. The pseudostarfort of our current interest was not utilized during the next American fortification craze, which was around the time of the Spanish-American War (1898). By the dawn of the new century, Fort Scammell was unarmed and unmanned, with its walls slowly crumbling away.

The threat of air attack during the First World War (1914-1918) set a whole new bunch of seacoast defense gears in motion, and positions for two 3" anti-aircraft guns were built at Fort Scammell. Which was wise, as had the German Empire conquered Canada and set up airbases therein, their Gotha heavy bombers might have been able to make it to Portland. |

|

Were Fort Scammell's air defense guns ever actually installed? Unknown, but it seems likely that they were not. From 1907 to 1937 House Island served the nation as an Immigration Quarantine Station, with several buildings installed elsewhere on the island for this purpose. Called "the Ellis Island of the North," surely the presence of many sullen, strangely-clothed and frequently Jewish foreigners made the War Department wary of supplying the island with weaponry of any kind.

|

House Island has been owned by various folks through the rest of the 20th century, and until fairly recently tour boats brought visitors there on a regular basis. I was unfortunately unable to make it there before those tours stopped, however, and as such managed to only get pictures of the fort's western bastion from some of Portland's other, more accessible fortifications.

Local sources tell us that great things are planned for House Island, up to and including the construction of sumptuous vacation homes thereupon, which will probably involve the obliteration of the Immigration Station's remaining buildings. Some sort of camping destination is said to be planned for the fort itself, which seems incredibly dangerous, opening a decaying fort to the nighttime stumblings of those unfamiliar with its hazards. Happy litigation, campground!

|

|

This was the closest I got to Fort Scammell in July of 2018: The western bastion, whose picture was taken from atop the unfinished walls of Fort Preble. This was the closest I got to Fort Scammell in July of 2018: The western bastion, whose picture was taken from atop the unfinished walls of Fort Preble. |

|

Lastly, a word on the spelling of the fort's name. It is sometimes spelled Scammel, such as it is on Google Maps, which is pretty much the world's "official map" these days. It seems clear that, as the fort was named for Alexander Scammell (whose name does not seem open to interpretation), it was misspelled somewhere along the line by someone official, and nobody thought it was worth the effort to get it straightened out...but the double 'L' spelling appears, to this correspondent at least, to be the correct one.

As mentioned, Portland Harbor has been protected by a variety of fortifications over the centuries, several of which remain in various states of disrepair. Though these forts look even less like starforts than does Fort Scammell, I feel compelled to include the following selections:

|

|

|

The original Fort Preble would have been a much more reasonable candidate for inclusion at Starforts.com than any of Fort Scammell's iterations, as Prebz was described to the Secretary of War as "an enclosed star fort of masonry, with a circular battery with flanks, mounting 14 heavy guns," in 1811. In 1808, a Regiment of Light Artillery was stationed at Fort Preble, and instructed to enforce the embargo (see more about Thomas Jefferson's Embargo Act of 1807 above) by any means necessary. Properly enforcing this embargo probably would have involved murdering about half of Portland's population, which by most accounts did not occur, so the garrison likely just sat in Fort Preble and tried to stay out of everyone's way.

|

For two periods in the late 1840's and early 1850's, Fort Preble was commanded by Captain Robert Anderson (1805-1871), who would latter be the commanding officer of Fort Sumter at Charleston, South Carolina, when it became the focus of every piece of artillery that the Confederacy could muster on April 12, 1861, which bombardment comprised the opening shots of the Civil War. That same war brought with it improvements to Fort Preble. The original starfort configuration was left intact, but added a single tier of casemated firing positions along three sides of the fort facing the water...or at least that was the intention, but work was left unfinished at the end of the war. Army engineer Thomas Lincoln Casey worked some of his magic at Fort Preble in the 1870's, building emplacements for 8-inch Converted Rifle Rodman Guns. Were these guns ever emplaced? Seems unlikely, given the history of Portland Harbor's armament or lack thereof. Fort Preble's starfort was callously obliterated thanks to the coldhearted necessities of the Endicott Period. Two 12-inch mortar batteries were built atop the bulldozed starfort, which were completed by 1901. A battery for two six-inch disappearing guns and another for a single 3-inch gun followed in 1906. |

|

Fort Preble's heroic, if unfinished, southeast wall. Fort Preble's heroic, if unfinished, southeast wall. Swinging iron shutters, designed by Joseph Totten, graced the firing embrasures of all American seacoast defenses that operated in the mid-19th century. There is evidence of these shutters in a great many places, but seldom does one see both shutters in place, if rusted unswingable. These are at Fort Preble, and seeing them in place got me much more excited than it reasonably should have. Swinging iron shutters, designed by Joseph Totten, graced the firing embrasures of all American seacoast defenses that operated in the mid-19th century. There is evidence of these shutters in a great many places, but seldom does one see both shutters in place, if rusted unswingable. These are at Fort Preble, and seeing them in place got me much more excited than it reasonably should have. |

|

One of Battery Rivardi's two 6-inch disappearing gun emplacements at Fort Preble. Also featured is the Spring Point Ledge Lighthouse and Fort Gorges, which we couldn't get away from even if we wanted to, which we do not. One of Battery Rivardi's two 6-inch disappearing gun emplacements at Fort Preble. Also featured is the Spring Point Ledge Lighthouse and Fort Gorges, which we couldn't get away from even if we wanted to, which we do not. |

|

During the Second World War (1939-1945) Fort Preble served as a Naval Net Depository, where the nets of the net-laying ships of the US Navy were stored...well, those nets had to be stored somewhere. Additionally, the fort was the control station for the Casco Bay Degaussing Range, whereby unduly magnetized ships would be demagnetized.

Fort Preble's last 3-inch gun was removed in 1946, and the fort was deactivated in 1950. In 1952 it was sold to the state of Maine, and became the campus for the Southern Maine Vocational Technical Institute, which is today known as Southern Maine Community College. |

|

|

Just a couple more of Fort Preble, because I would hate to think you didn't feel as though Just a couple more of Fort Preble, because I would hate to think you didn't feel as though

you got your money's worth of Fort Preble from this page which is not really about Fort Preble. |

Fort Gorges ...was built on Hog Island Ledge in Casco Bay from 1858 to 1864. Designed by Colonel Reuben Staples Smart (1814-1892) but mostly built by Thomas Lincoln Casey, 'twas named for Sir Ferdinando Gorges, a gentleman who played a role in the instigation of Maine as an English colony in the 17th century. Fort Gorges is similar in size and shape to Fort Sumter, but it is made of granite, as opposed to Sumter's brick. This fort was built to support forts Scammell and Preble, but was considered obsolete before it was even finished. How that must have bruised the ego of the newborn Fort Gorges! |

|

|

|

Fort Gorges was designed to mount 28 guns on each of its two tiers, and an additional 39 atop its walls. Despite being recognized as useless, in 1871 the determination was made to dump sand and sod along the top of the fort's walls, which was considered a more defensible firing platform than masonry alone. Some improvements were made to the fort, but Congress ordered the cessation of all such works in 1876.

|

Fort Gorges' parade ground, sometime "after 1933." Library of Congress, you are an American history lover's dream. Fort Gorges' parade ground, sometime "after 1933." Library of Congress, you are an American history lover's dream. |

|

Though Fort Gorges was reportedly never manned, it apparently was armed. 34, 10-inch Rodman Guns were mounted in its casemates for a period, but were all removed by 1898. Left behind was a single 10" Parrott Rifle, which was somehow in some location, unmounted, on top of the fort's walls. A 10" Parrott Rifle weighed over thirteen tons, and it's a good bet that it wasn't delivered by helicopter in 1898.

"Where shall we place the Parrott Rifle, sir?" "Oh, I dunno, put it up atop the walls someplace." "...yes, sir. Shall we...uh...mount it or anything?" "No, sergeant, but make sure at least four of your men get hernias from doing this." |

|

Allegedly that Parrott Rifle is still somewhere at the fort, and while I can't find it from the satellite imagery, I have been assured by a gentleman who visited Fort Gorges in the early 1990's that the gun is, in point of fact, there.

Fort Gorges was used to store mines during the Second World War, and was bought by the city of Portland in 1960. Today it is accessible by tour boat or water taxi. Visitors are encouraged to bring flashlights, so that they can help to search for the lost Parrott Rifle.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|